Dispatches, Mexico

Mexico’s LGBT Community Faces Violence Despite Major Gains In Civil Rights

August 4, 2011 By Daniel Hertz

MEXICO CITY — The men who killed Quetzalcoatl Leija Herrera, 33, beat him with rocks just steps from the main square of Chilpancingo, about two hours from Mexico City in the state of Guerrero. Exactly two months later, on July 4, the body of 21-year-old Javier Sánchez Juárez was found in Zumpango del Río, just five miles from Chilpancingo. He had also been beaten to death.

Both murders made headlines across a country that has been traumatized by violence over the last five years. But these were not statistics from Mexico’s bloody drug war: Leija Herrera and Sánchez Juárez, both local Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender (LGBT) activists, were apparently killed because they were gay.

The killings darkened what might otherwise have been a time of celebration in the Mexican LGBT community. At the end of June, the country saw its largest-ever pride parade, with up to a million people marching between the skyscrapers that line the Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City; and this August marks one year since the Supreme Court upheld the gay marriage law passed by the capital’s municipal government.

While the United States lurches towards acceptance and legal equality for its LGBT citizens, its neighbor to the south is struggling with the same issues. Rights for sexual minorities have become the subject of heated political debates in both countries over the last decade and a half. As in the U.S., the result in Mexico has been a patchwork of contradictory social and legal regimes, often changing dramatically from state to state, city to city, or even neighborhood to neighborhood. Here, some of the hemisphere’s most progressive laws coexist with deeply-rooted social conservatism, discrimination, and violence.

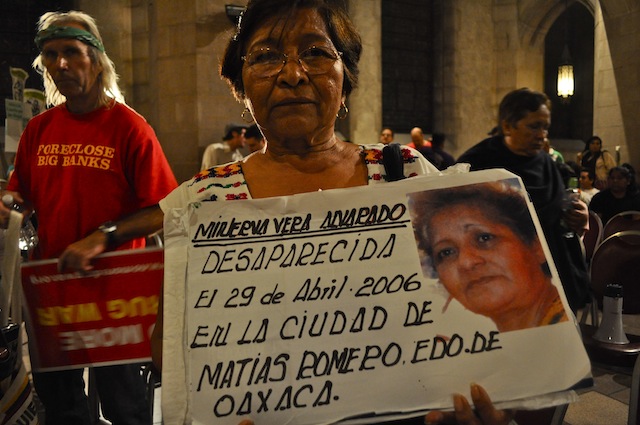

Mexico’s national government does not keep any official statistics about hate crimes; the Federal District (DF), the jurisdiction that covers Mexico City, charged its law enforcement community with doing so in a 2007 law, but so far it has failed to record a single offense against an LGBT victim. Still, those who study the issue are sure that the murders in Guerrero were not isolated incidents, because while the police do not record hate crimes, various researchers and non-profit groups have come up with their own numbers.

In 2009, a coalition of NGOs and the gay media outlet “Letra S” did their own investigation using newspaper clippings. Counting only homicides in which the victim was reported to be either gay, lesbian, transsexual, or cross-dressing; the victim and the perpetrator did not know each other; and there was no robbery, they found an average of 67 murders per year between 2004 and 2008. Some neighborhoods were particularly hard-hit: the Cuauhtémoc borough of Mexico City, which contains the Zona Rosa, Mexico’s premier gay nightlife district, had seen 43 killings since 1995.

“The problem with all the numbers we have,” said David Razú, a Mexico City legislator from the liberal Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), “is that when we talk about 400, or 325, or whatever number, we lack the legislation, we lack the will…to be sure when we say, ‘The problem is this big.’”

As a result, the statistics from researchers like “Letra S,” Razú said “are probably low.”

Even so, comparing these “low” numbers to those from other countries paints an alarming picture. In the United States, where hate crimes are officially recorded by the FBI, only one anti-LGBT homicide was recorded in 2009, and five in 2008, the latest years for which data is available. Using broader criteria than the FBI, the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs found an average of 22 hate-motivated murders per year. These numbers suggest LGBT Mexicans face anywhere from nine to sixty times the danger of lethal violence as do their American counterparts.

Yet the crowds who closed down Mexico City’s main boulevard in late June on their way to the main square, the Zócalo, attest to the impressive victories of Mexico’s gay rights movement. At the square, drizzling rain failed to disperse the marchers, who waved rainbow flags in front of a makeshift stage where performers covered “I Will Survive,” the music echoing off the massive Metropolitan Cathedral on the other side of the plaza. Occasional chants mocked Mexico’s conservative president: “Felipe Calderón también es maricón,” or “Felipe Calderón is a faggot too.”

This show of confidence is the result of staggering changes to Mexican law and society over the last decade, even eclipsing in some ways those in the United States. In 2002, Enoé Uranga, a congresswomen who is also a lesbian, proposed the first civil union bill in Mexico’s history; it was defeated without a floor vote. Just five years later, the northern state of Coahuila passed a similar law, giving legal recognition to same-sex couples there.

Then, in 2009, the legislature of the Federal District voted 39-20 to allow marriages between couples of the same sex. President Calderón’s attorney general challenged the constitutionality of the new law, but on August 6, 2010, the Mexican Supreme Court upheld gay marriage in the capital. A few days later, it ruled that marriages performed in Mexico City had to be recognized throughout the country. With that decision, any couple that could afford a trip to the Federal District and back could be married. By contrast, the U.S. Defense of Marriage Act explicitly allows American states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states.

Many supporters of these legal changes say the real victory is a revolution in social norms. “I am absolutely convinced,” said Razú, who helped write the gay marriage law, “that these reforms are going to lead to a decrease in discrimination. If your own laws are discriminatory, how can you ask society to stop discriminating?”

In many places, this social revolution has already happened. On any day of the week, Mexico City’s Zona Rosa neighborhood is full of gay couples and individuals openly flouting Mexico’s traditional gender roles in appearance and behavior. And increasingly, gay couples are able to openly show affection in other parts of the city—and outside it.

“I’ve been with my partner all over the country,” said Alejandro Reyes, the editor of OHM, a major gay magazine published in Mexico City. Although in many places “people make jokes,” in larger cities like Puerto Vallarta and Guadalajara it’s “common to see gay couples holding hands on the street.”

Noé Ruiz Malacara, who works for the gay rights group San Elredo in Coahuila state, sees the transformation too. “Coahuila has changed drastically,” he said, adding that in Saltillo and Torreón, the state’s largest cities, gay partners “can walk holding hands at the mall or on the street and no one will say anything. Homophobia hasn’t dropped by 100%, but it’s been a good percentage.”

8 Comments

[…] Mexico’s LGBT Community Faces Violence Despite Major Gains In Civil Rights […]

[…] the title of my first published article! It is here. A […]

[…] Mexico’s LGBT Community Faces Violence Despite Major Gains In Civil Rights […]

[…] Mexico’s LGBT Community Faces Violence Despite Major Gains In Civil Rights new TWTR.Widget({ version: 2, type: 'profile', rpp: 15, interval: 6000, width: 280, height: 300, theme: { shell: { background: '#306899', color: '#ffffff' }, tweets: { background: '#ffffff', color: '#000000', links: '#cd1613' } }, features: { scrollbar: true, loop: false, live: false, hashtags: true, timestamp: true, avatars: false, behavior: 'all' } }).render().setUser('LatinAmDispatch').start(); You are here: Home » Regions » Southern Cone » Chile » […]

[…] Violence against Mexico’s LGBT community is darkening what should be its shining moment — the passage of milestone legislation, including a law legalizing gay marriage in Mexico City. Daniel Hertz reports from Mexico’s capital. […]

[…] rejection of the idea of adoption by gay couples is widespread in Mexico — where violence against the LGBT community continues — it tends to decrease with age. Seventy percent of adults between the ages of 30 […]

[…] a homofobia por lá ainda é forte (afinal, preconceito não se vence somente com um decreto). A violência contra homossexuais ainda é grande e a opinião pública é bastante desfavorável a idéia de adoção de crianças por casais […]

[…] after the nation’s Supreme Court’s ruling. Both were beaten to death in an apparent connection to the gay community, according to the Latin America News […]

Comments are closed.