Dispatches, Mexico, Photo Essays, United States

Caravan For Peace ‘Plants Seeds’ In New York City

October 10, 2012 By Carolina Ramirez

NEW YORK – On the night of Sept. 6, a procession of a few hundred people crossed Harlem from east to west before gathering in front of Santa Celicia Parish in the heart of El Barrio, illuminating the steps of the church with hundreds of tiny candles and filling the sidewalk with images of friends and family members lost to the drug war. There, they began to read from a list of dead and disappeared.

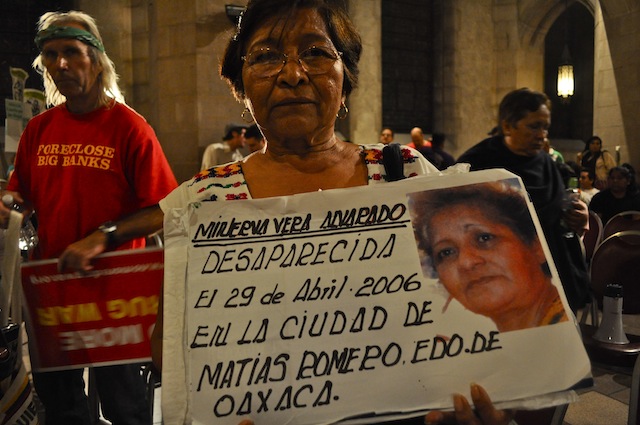

“Regina Martines,” someone called. “¡Presente!” the crowd responded. “Andrés Asención Gonzáles… ¡Presente! Minerva Vera Alvarado… ¡Presente!” The reading quickly dissolved into a cacophony of names yelled out by the crowd.

After a 6,000-mile journey across the United States aimed at raising consciousness about a drug war that’s claimed over 60,000 Mexican lives, Javier Sicilia says there’s no one moment when he felt he was making a major impact.

But that doesn’t mean he’s pessimistic.

“It’s been a slow process,” Javier Sicilia told the Latin America News Dispatch. “We’re planting seeds for peace.”

Sicilia, who lost his son in 2011 to gang-related violence, led a group of activists calling themselves the Caravan for Peace with Justice and Dignity across two dozen U.S. cities this summer, from San Diego to Washington. They destroyed legally purchased weapons outside a Texas gun show, dropped off a suitcase filled with red-stained one-dollar bills at an HSBC branch in Manhattan, and lobbied for the attention of politicians in Washington.

The activists arrived without a set agenda. For the people riding in the Caravan, “planting seeds for peace” means starting conversations and building bridges.

“We didn’t bring up legalization,” Pepe Rivera of the Caravan said in an interview. “We thought it would alienate a lot of people.”

Instead, Rivera says, the Caravan hoped to get people talking about alternatives to using violence to tamp down drug use.

“As long as that dialogue happens, we win,” Rivera added.

In addition to calling attention to an estimated 60,000 deaths caused by the U.S.-led Drug War, the Caravan also tried to spark discussion about the impunity, corruption and organized crime that fuel violence in both Mexico and the United States.

The overarching point of the trip, Sicilia says, is to show people that both Americans and Mexicans share the responsibility for the Drug War’s violence, and both countries suffer its devastating effects.

For many in the Caravan, marching with the African-American community in Chicago served as one of the highlights of the trip. The Mexican activists, many if not most of whom had lost friends or relatives to Drug War-related violence, saw parallels between the bloodshed in their country and the skyrocketing murder rate in the city of Chicago—a city where homicides are often connected to the drug trade.

The Caravan held a peace rally in the Midwestern city and marched through the African-American neighborhoods most heavily affected by gun violence.

Not coincidentally, the Caravan scheduled its first march in New York on Sept. 6 through the streets of Harlem.

The march and vigil passed through some of Harlem’s busiest streets, where local residents watched curiously as protesters yelled in both English and Spanish.

“Alive they took them, alive we want them!” “¡Vivos se los llevaron! ¡Vivos los queremos!” resonated down Dr. Martin Luther King Blvd.

During a vigil held in Harlem’s Riverside Church before the march, members of the Caravan, organizers from New York City-based organizations including Make the Road and the Mexican protest group Yo Soy 132 gathered with community members to commemorate those lost to the violence. Family members of the murdered and disappeared told their stories, holding up signs and photos of their loved ones.

Among the organizations that participated in the Caravan’s New York stop were members of Vocal New York, a collective of community organizers that works to empower former drug users, ex-convicts and people living with HIV.

“We are here today to support the caravan for peace, justice and dignity,” said Bobby Tolbert, a board member of Vocal New York who lives in the Bronx. “To let them know that this drug war that they are fighting is a universal problem and we all need to be on the same page to fight it.”

On Sept. 7, during a press conference at City Hall, Sicilia said the Caravan hopes to bring a proposal to the Mexican and U.S. governments to bring into conversation the issue of drugs and violence. “We come to bring the agenda for peace,” he said.

During his speech, Sicilia identified the Caravan with Occupy Wall Street, which he grouped with other social movements like the Zapatista uprising in southern Mexico and the student-led Yo Soy 132 movement.

“We are part of that 99 percent,” Sicilia said. “The 99 percent speaks to the excluded in the United States and in the world in general.”

During the march and demonstrations in New York’s financial district, Caravan protesters marched though Wall Street, denouncing the flows of dirty money that fuel the drug, weapon and mass incarceration industries.

At Zuccotti Park, protesters held a bilingual people’s mic—a method of speech-making popularized during the Occupy movement where the audience amplifies the speaker’s voice by repeating what he or she says—to tell the stories of Belén and Mahoma López. Belén is a member of the Caravan whose brother was disappeared in 2007 and Mr. López is an activist organizing for worker’s rights in New York City with the Hot and Crusty Workers Association.

“I am here because my sister was disappeared on April, 29, 2006 in Oaxaca,” said Teresa Vera Alvarado, who has been with the Caravan since it began in Tijuana. “I have walked the entire Mexican state asking for justice and found nothing. But I am here to make the victims visible. I am here to make their image public.”

Francisco Ramirez, a Mexican-born plumber and activist who helped organize the Caravan’s events in New York as part of the Yo Soy 132 movement, said he was disappointed that big-name politicians like Mayor Michael Bloomberg didn’t show up.

Nevertheless, Ramirez said he felt encouraged.

“There was an effect. Maybe not in a massive way, but maybe there were people who heard the things that were said, and saw the faces and took photos,” Ramirez said. “I think a message was sent.”

Click the first image to view a slideshow of the Caravan for Peace in New York.

[nggallery id=1]< Previous Article

1 Comment

[…] – like button',unescape(String(response).replace(/+/g, " "))]); }); Caravan For Peace ‘Plants Seeds’ In New York CityNEW YORK – On the night of Sept. 6, a procession of a few hundred people crossed Harlem from […]

Comments are closed.