Central America, Dispatches, Nicaragua

In Nicaragua, the Campaign Trail is Replete With Memories of Revolution

July 11, 2016 By Jonah Walters

MANAGUA, Nicaragua — On Friday, supporters of Nicaragua’s ruling Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional gathered in Managua to celebrate the 37th anniversary of the repliegue táctico a Masaya (“tactical retreat to Masaya,” in English).

Hundreds piled into buses flying Sandinista flags to make the traditional journey to the nearby city of Masaya, while others made the 25-kilometer trek on foot or by motorcycle.

The annual repliegue, as it’s known, commemorates June 27, 1979, when thousands of Sandinista militants and collaborators — including current president Daniel Ortega and left-wing opposition figure Mónica Baltodano — began their clandestine journey from Managua, the capital, to Masaya, a smaller city to the southeast. Along the way, they were pursued by Guardia Nacional troops and harassed by aerial bombardments.

At the time, Managua was still controlled by the dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle, whose Guardia Nacional violently suppressed revolutionary activity. But Masaya had recently come under the control of the FSLN, providing a valuable base of operations for the revolutionary movement.

Today, FSLN supporters celebrate the repliegue as a watershed moment in the revolutionary struggle. The celebration’s political resonance was enhanced this year as Ortega looks to win a fourth term in November while facing accusations of election-tampering from Nicaragua’s opposition.

Thousands of FSLN supporters gathered on Friday at the intersection of Paseo de la Únion Europea and Avenida Miguel Obando y Bravo in Managua.

The headquarters of the Ministerio de Economía Familiar Comunitaria, Cooperativa y Asociativa (MEFCCA), an agency founded by the Sandinista government to encourage popular economic development, towered above the demonstrators, displaying FSLN flags and a massive banner advertising Ortega’s reelection campaign.

Preparations began as early as 7:00 AM, as vendors arrived to sell t-shirts emblazoned with Ortega’s re-election slogans. Crowds began to form in mid-afternoon as banks of speakers played pop songs, including Ortega’s 2011 election anthem — a version of “Stand By Me” with its lyrics altered to praise the Sandinista revolution.

Around 5:00 PM, Ortega addressed the crowd, taking the opportunity to condemn the recent police killings of black citizens in the United States and praising the accomplishments of the 1979 revolution.

If he is re-elected in November, as most observers expect, Ortega will serve his third consecutive term in office, and fourth term overall. In 2014, he supported a constitutional amendment abolishing presidential term limits, clearing the path for a prolonged administration.

Recently, the Nicaraguan supreme court — which some accuse of a pro-FSLN bias — removed the Partido Liberal Independiente, the primary opposition party, from the control of Eduardo Montealegre, instead ruling in favor of former general secretary Pedro Reyes.

The ruling effectively barred the PLI and its opposition coalition, the National Coalition for Democracy, from participating in this year’s presidential election, inviting allegations of Sandinista election tampering from opposition figures like legislator Victor Hugo Tinoco.

But Ortega still enjoys tremendous support in Nicaragua, as demonstrated by the turnout at Friday’s repliegue, where hundreds of supporters donned t-shirts bearing the slogan “Onwards with Daniel to more victories.” A banner displayed at the rally site and addressed to Ortega and Rosario Murillo, the president’s wife and government spokesperson, read “Here are your allies.”

Luis Téllez, a taxi driver from the Los Ángeles neighborhood of Managua, spoke to Latin American News Dispatch the day after the repliegue, gesturing proudly down the length of Avenida Bolívar, which runs past the Plaza de la Revolución towards Lake Xolotlán. “In 1979, when the guerillas came to Managua, we marched down this street,” he said. “I was one of them.”

He reached into the glove compartment of his taxi to pass me a sepia-colored photograph of himself, bearded and decades younger, wearing camouflage.

Pointing at the Palacio Nacional, he told me excitedly about the guerilla action that took place there in 1978, when Sandinista fighters held more than 3000 Somoza-era officials hostage, successfully demanding the release of 50 imprisoned Sandinistas.

He hesitated a moment when asked if he still supports Ortega and the Sandinista organization. “Yes,” he finally said. “Good social programs.”

Ortega’s administration has been characterized by ambitious poverty reduction initiatives, many carried out by MEFCCA, which have benefited from the financial support of Venezuela’s Bolivarian government.

But even there at the Plaza de la Revolución, there were others who remembered the revolution differently.

Every day for 34 years, José Félix Cano, 80, has journeyed the ten blocks from his home in Managua’s Barrio Julio Buitrago to the plaza, where he sells soft drinks from a cart.

While he acknowledges that some things have improved during Ortega’s presidency, like parks and plazas, he has never supported the Sandinistas. And he doesn’t support them now.

Gesturing at the plaza behind him — which today contains eternal flames for deceased Sandinista icons like Tomás Borge and Carlos Fonseca — he recalled that it used to be known as the Plaza de la República. “It was better that way,” he said.

But not everything was good back then. There was tragedy too.

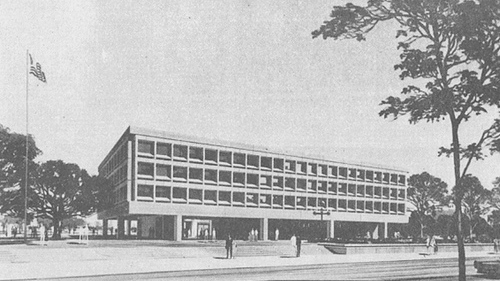

Cano recalled the earthquake of 1972, which leveled large parts of Managua and killed more than 6000 people.

“The earthquake occurred at 12:30 at night,” he recalled. “There were crowds of people here, dancing. When the earthquake came, the Palacio Nacional, the cathedral, all of it came down on top of them.”

It is widely accepted that Somoza and his associates appropriated much of the donated foreign aid intended to support redevelopment after the earthquake, provoking a national scandal that assisted revolutionary groups like the FSLN in mustering popular support.

“The plaza stayed totally destroyed. Nothing was rebuilt for at least three years afterwards,” Cano recalled, shaking his head.

Avoiding danger, Cano spent the duration of Nicaragua’s revolutionary transformation and the ensuing war in Costa Rica. But many of the neighbors he left behind became Sandinista guerillas, including the man who sells him the sugar he uses in the fruit-flavored punches he sells from his cart. “Now, we don’t talk about the war,” he said.

Cano’s biggest complaint about Ortega’s current administration has to do with Managua’s growth, which he attributes to Ortega’s development initiatives.

Nevertheless, he is optimistic. “Things are good in Nicaragua right now,” he said. “But things have been really bad in the past.”

On July 19, Sandinistas will gather once again — this time in the Plaza de la Revolución, where Cano sells his soft drinks, to celebrate the ultimate triumph of the Sandinista coalition over Somoza and the Guardia Nacional.

Ortega will again display his credentials, mustering support for his controversial re-election campaign with memories of Nicaragua’s 37-year-old revolution.

About Jonah Walters

Jonah Walters is regular contributor to Jacobin and a graduate student in geography at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.