Brazil, Features, Southern Cone

In Brazil, Growing Inequality Fuels Fires Burning the Amazon

October 17, 2019 By Marina Guimaraes

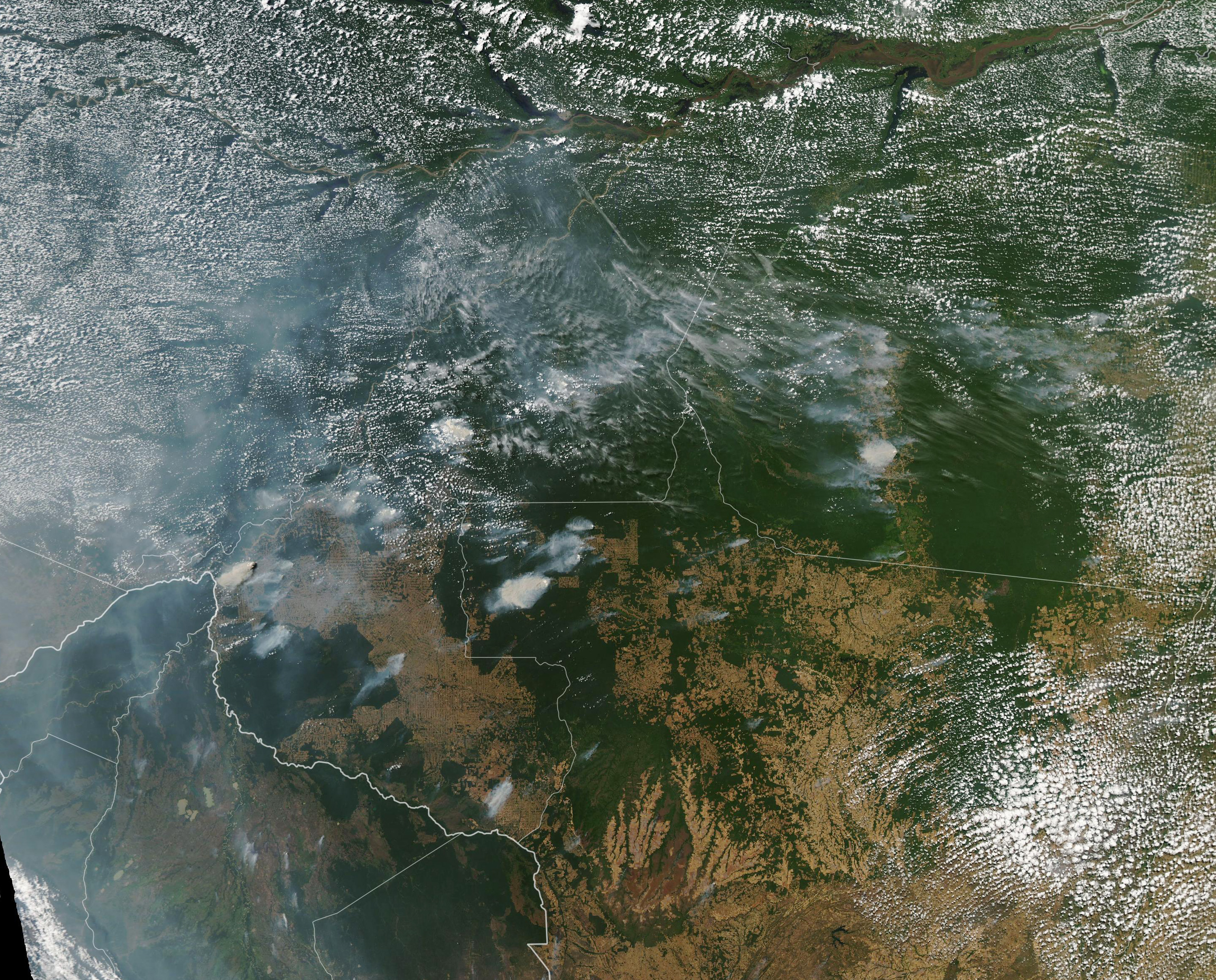

NEW YORK — The fires in the Brazilian Amazon continue to burn more than two months after they first darkened the skies of São Paulo and caused an international outcry. As the rainforest speeds closer to its tipping point — when it will no longer be able to recover from deforestation — most of the outrage is focused on Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s environmental policies. But experts say the fires will continue, even if Bolsonaro changes these policies.

The country’s extreme social and economic inequality also contributes to deforestation. The number of fires in the rainforest tripled from 2018 to 2019, mirroring the growth of inequality in Brazil. According to a study conducted by FGV Social, a Brazilian higher education institution and think tank, inequality in the country has grown steadily since the end of 2014, with the income of the poorest half of the population declining 17% and the income of the richest 1% growing by 10%. The study cites higher cost of education and a rising unemployment rate as the main reasons for these numbers.

Gabriel Santos is a member of the Brazilian political movement Acredito, which aims to decrease inequality in the country and engage more Brazilians in politics. Santos, who came to New York City for last month’s Climate Week, running in conjunction with the United Nations General Assembly, said the sole focus on the environment in combating the Amazon fires is the wrong approach.

“Deforestation and preservation are also economic, social and political matters,” Santos said. “The singular focus on the environmental question, however, ignores all other factors that also contribute to deforestation.”

Data provided by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, shows that 40% of Brazilians older than 25 did not finish elementary school. Schools play an important role in teaching young Brazilians about conservation and sustainability, but they fail to do so when their students drop out. “How do you expect people who have never had access to education to be aware that they are indeed committing a serious crime, mostly in times of an economic crisis?” Santos said. “Of course, there are people who are consciously deforesting, but that is not always the case, and this is something we need to start talking about.”

Brazil is the world’s largest exporter of beef, and 80% of the rainforest’s deforestation is related to cattle ranching, according to the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. The land’s low cost and relatively easy transportation make cattle ranching a profitable and attractive business opportunity, together with soy cultivation in the Amazon, the study said. But the perceived economic benefits aren’t the only reason people are burning the rainforest, said Frederico Seifert, a finance manager at an environmental performance analysis company in Brazil called SITAWI.

“There is a predominantly false idea among some people in the region that burning up trees in the Amazon to make space for cattle and soy cultivation is an easy way out to make profit out of the forest, mostly poor Brazilians after the financial collapse,” Seifert said. He added that this idea undermines other reasons people set fires in the Amazon. “Socially, Brazil is still behind, and this is one of the main issues that affect all significant areas in the country. Environmental consciousness is missing. People need to be educated and be aware that we actually need the Amazon.”

The rhetoric of Bolsonaro and his administration hasn’t helped raise this consciousness. Before he assumed office, Bolsonaro chose Ernesto Araújo as Brazil’s next foreign minister, despite — or perhaps because of — Araújo’s claims that climate change is a Marxist plot, echoing some of Bolsonaro’s own beliefs. In August, Bolsonaro fired Ricardo Galvão, the director of Brazil’s National Space and Research Institute, known as INPE, after Galvão said deforestation was 88% higher in June 2019 than it was in the same month in 2018. In response, Bolsonaro called INPE’s findings “lies” and said two months later at his first UN General Assembly that the forest remains “untouched despite related NASA data which proves the increase of the fires.”

Some of Bolsonaro’s non-environmental policies are also contributing to the inequality growth, critics say, which may add fuel to the fires. Since his inauguration, Bolsonaro has been trying to transfer control of decisions on Indigenous land rights from Funai, a Brazilian agency that works for the protection of the Indigenous, to the Ministry of Agriculture, a move largely seen as reducing the power of the Indigenous and transferring it to large-scale farmers and other industries that want to develop the Amazon.

Franz Baumann, former United Nations special adviser on environment and peace operations, connected the Bolsonaro administration’s actions directly to the Amazon fires. “There have always been fires in Brazil — man-made, since natural ones are quite rare — but the uptick this year, induced by the new government, is concerning,” Baumann wrote in an email.

While opening up the Amazon for development could allow for short-term economic growth for some Brazilians, it doesn’t address the lack of education that lies at the heart of the country’s inequality. Seifert said addressing this issue is crucial in saving the Amazon. Banning deforestation alone isn’t enough.

“Environmental policies need to achieve more of an economic character,” Seifert said. “Otherwise this problem will never end. Brazil needs to stimulate the national economy so that it will grow, and people won’t feel the need to deforest anymore.”