Latinx Workers Keep New York City Moving

NEW YORK―Immigrants make up the city’s essential workforce, who get up in the morning to work in supermarkets, disinfect subway cars, deliver take-out, and drop off merchandise at bodegas and pharmacies.

Many of these workers are undocumented, but their legal status has not prevented them from maintaining essential business operations. The contributions of Latinx workers, especially those who are undocumented, often go unrecognized. Yet they are the New Yorkers who are most likely to contract the coronavirus and die from it. Latin Dispatch spoke with Latinx essential workers to understand how they are handling the pandemic.

Supermarkets, bodegas and warehouses are the heart of survival in New York City. Their workers are essential so that millions of people can continue to eat. Photo credit: Heriberto Paredes.

As of May 7, 19,540 people had died of COVID-19 in New York City, though the real total is likely to be higher. Latinx and Black New Yorkers have had the highest rates of infection and mortality during the city’s outbreak. Data released by city health officials on April 6 showed that Latinx patients represented 33.5% of those who had died of COVID-19, despite making up only 29% of the city’s population. Black and African American patients represented 27.5% of deaths, while they only make up 22% of the city population.

The federal government has extended social distancing measures until May 15. New York City, the hardest hit urban area in the country, still has no end in sight for social distancing. While the daily death toll in New York City has now entered a steady deadline, more than 200 people are still dying of COVID-19 every day.

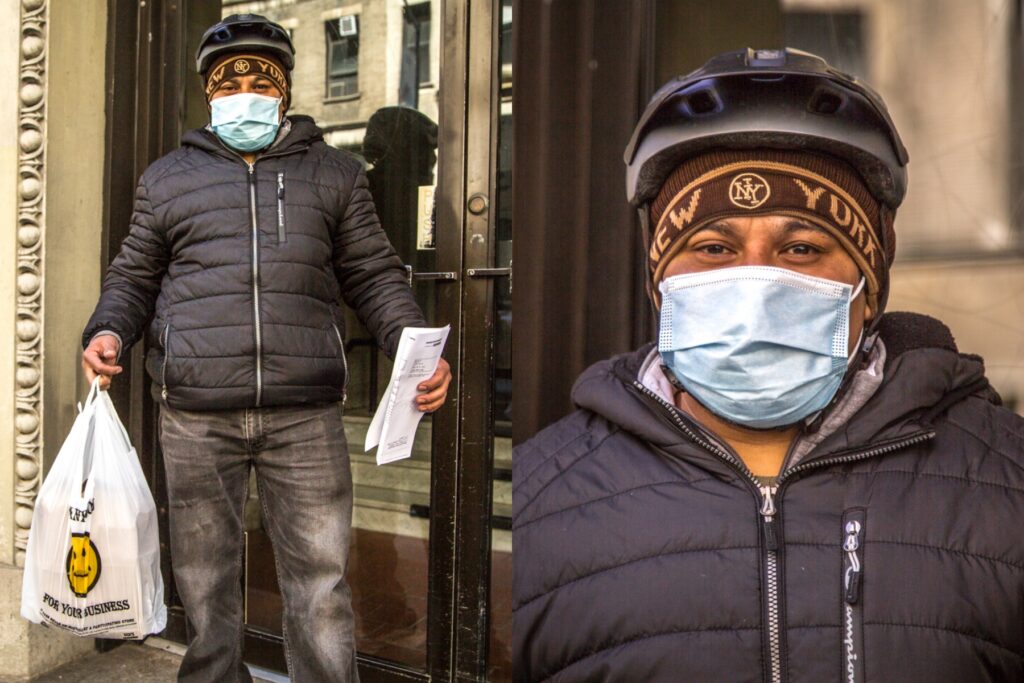

Delivery workers continue to shuttle food to costumers around the city. Many work directly for restaurants, while others use applications. Photo credit: Heriberto Paredes.

Just as confirmed cases of infection are on the rise, unemployment is at an all-time high. According to the latest data released by the Labor Department on May 8, more than 20.5 million jobs were lost during April.

Many immigrants continue to work daily, unable to stay home from jobs like food delivery, stocking grocery stores and driving cabs.

“[The pandemic] is another moment of tension between the center and the margins,” says Marco Castillo, has lived between Mexico City and New York City for the past several years. He is an organizer with the Transnational Peoples’ Network and for the past decade has worked with different immigrant organizations and communities.

“Many people do not understand the meaning of the coronavirus or the precautions that they are being asked to take,” he says.

A market worker from Tlapa, Guerrero, Mexico, who prefers to remain anonymous. He is one of the fortunate whose employer provides PPE. Photo credit: Heriberto Paredes.

The Transnational Peoples’ Network works with the Mexican immigrant community on the East Coast, mainly in New York, but also in New Jersey and Connecticut. Many of its members are indigenous, who for decades have been discriminated against by both the US government and the Mexican government.

“Many of them are delivery men and delivery women or taxi drivers, and in times of social distancing and pandemic, they are the ones who cannot stop working,” says Castillo. “Abiding by the rules is a matter of privilege, it is a matter of conditions, people living from paycheck to paycheck cannot do it.”

Some members of the migrant community do not have the protective equipment or minimum conditions necessary to continue working safely.

Photo credit: Heriberto Paredes.

Photo credit: Heriberto Paredes.

“My sister works as a cleaner in a bank, which is still open,” says Xugey, who is from Puebla, Mexico. “She still has to go to work and they don’t give her a mask or any protective material, she needs to pay for it herself.”

Immigrants impacted by the pandemic are demanding aid programs that they can access. The rent is still due, bills are arriving and there are families who have already fallen ill and had to stop working.

The #YNosotroQué (What About Us?) demonstration that took place on April 21 in Midtown Manhattan demanded solutions for the immigrant community, many of whom cannot access federal aid and stimulus money.

Photo credit: Heriberto Paredes.

In addition to Mexican immigrants, Central and South Americans and people from the Caribbean make up the New York City workforce. Rita Michelini is originally from Caracas, Venezuela, has been living in New York for a little over three years. She is five months pregnant and works as the head of the fish section in a supermarket in Morningside Heights, next to Columbia University. She spent several weeks in quarantine, unable to go to the doctor for a check-up.

“My doctor told me not to come because it was too dangerous for pregnant women, but now I’m starting to get desperate and I’d better come to work, just four days a week,” she says.

Photo credit: Heriberto Paredes.

“As soon as there is less food, and when the crisis becomes deeper, what will become obvious is how profoundly unequal New York is,” says Castillo. “There will be those who will get sick but will survive, and may even get ahead, and those who will lose everything. And that’s when indigenous peoples will reach out and make use of their community networks, as they have always done.”

Photo credit: Heriberto Paredes.

Photo credit: Heriberto Paredes.

Photo credit: Heriberto Paredes.