Demands for Land and Housing Continue After Guernica Eviction

This story was co-published with NACLA.

José Iza’s cell phone won’t stop ringing. It is the week after the eviction of the Guernica occupation. He has been following up with the families that were left with nothing. José is asthmatic and knows that contracting Covid-19 would be dangerous for him. He only speaks with the neighbors wearing a face mask and keeping his distance.

Since the eviction, José has volunteered for the local government, working on re-locating and aiding the families left out on the streets, “one by one,” as he explains. This help might be a temporary place to stay, money for rent, or medical assistance.

Only a few weeks ago, José was hopeful, building a precarious, small house in the Barrio 20 de Julio, one of four divisions on the 100-hectare (250-acre) parcel homeless families had occupied in Guernica. The occupation was in the municipal seat of the Presidente Perón district, 23 miles south of the city of Buenos Aires. José had heard there was a chance to access land in the barrio and a relative invited him to occupy right next to him. José moved to Guernica the next day. It was July 21, the day after the occupation started. He settled on a plot, cut the grass, cleared the soil, potted flowers, and began to build a small shelter, the first part of the house he was dreaming of.

José’s work as a carpenter had dried up during the pandemic, and he could not access any government aid to sustain himself. “Before the coronavirus, I’d make four or five thousand pesos a day, and that allowed me to rent and to pay for my needs,” he said, or between $50 and $65. But after May, almost two full months since the lockdown started, he ran out of money.

José was one of the hundreds who settled spontaneously on the flatland, searching for a place to make a home. Guernica was the biggest land occupation in the country.

Occupations of land in Argentina started in 1981, during the last military dictatorship. Around 211 hectares were occupied that year. A decade later, in 1990, there were over 100 settlements in the Province of Buenos Aires. There have been at least 1,800 new occupations in the province so far in 2020, as the housing deficit grew with the Covid-19 crisis and rental prices continue to increase. Guernica stood out because of its size and the unique context.

“We do not ask for anything as a gift,” residents told the media during the 100-day occupation. The people who settled in Guernica demanded state support so that they could access land ownership and slowly build their own houses. They received support from Left and progressive political organizations such as the Worker’s Party (Partido Obrero) and Barrios de Pie. With an economic crisis accelerated by the pandemic and 40.9 percent poverty at the national level, the possibility of owning one’s own home is becoming more and more difficult, nearly unattainable for middle and working class people if it is not through inheritance.

The families that occupied Guernica were, like so many others, homeless. They included single mothers who escaped from gender violence with their children, men and women who were unemployed in the pandemic and no longer had money to pay rent, and so many other victims of the overlapping oppression that is being poor in a world where decent housing, despite being a constitutional right, feels like a luxury.

The Guernica occupation was a community like any other. People looked out for each other, shared meals, and kids gathered to play. An Asamblea Feminista, a Feminist Assembly, was founded as a place for women to organize. Residents dug trenches to prevent police cars from entering. José became a delegate for his block. There were three levels of hierarchy: block delegate, general delegate, and spokesperson for the occupation.

But right after the first families settled in, the alleged owners filed police and judicial reports, claiming that their constitutional right to private property was being violated. Although occupying the land is not a crime in and of itself, the self-appointed owners were entitled to file civil complaints. Instead, they filed criminal charges. Progressive organizations strongly condemned the charges, arguing that criminal proceedings on this issue are illegitimate and that they are lacking evidence to prove they are the true owners of the lands. The alleged owners argue that the land was not appropriate for housing for the families, because it is not possible to construct a sustainable power line or water pipe system. They claimed plans to create an artificial lake where the occupation stood, to adorn the spaces between the rugby, field hockey fields, and the house in their gated community.

A make-shift home constructed at Guernica, outside Buenos Aires, during the occupation. (Photo: Gala Abramovich)

The new local government in Buenos Aires Province took office on December 10, 2019 and only governed for three months before the coronavirus pandemic arrived. Headed by the popular ex-minister of economy Axel Kicillof, the provincial government began a series of negotiations with the families living in the occupation. They installed five tents at the occupation bringing together efforts of diverse Ministries, such as Community Development, Justice and Human Rights, Security, and Women, and Gender Policy. Andrés Larroque, a community organizer and now Minister of Community Development, moved his office to the occupation and reassured the families that they would take a comprehensive approach to provide solutions for everyone. They offered a “housing expansion” project through the delivery of materials and grants to improve houses, or an emergency housing subsidy for those who had difficulty renting. Both these initiatives, according to the government, were the result of the census they had carried out in the field.

While the government took these steps to respond to the families of Guernica, the clock kept ticking. After the alleged owners filed their complaints, Judge Martin Rizzo and prosecutor Juan Condomí Alcorta ordered an eviction. The government and organizations managed to delay it twice. But the dreaded moment came at dawn on October 29.

The night before, José was working hard in Guernica. He had already signed an agreement to accept the government’s help and had left the area a month earlier. Now, his personal task was to save his fellow occupiers, those who were still on the land, and would be evicted within the next few hours. Around 8 PM the night before the eviction he gathered 60 neighbors and was set to help them leave when he saw tensions within the camp were rising. There were many families willing to defend their right to occupy Guernica and insisted on demanding the government accept their claims. Some others thought it was safer to leave the occupation and accept the government offers. But at 11:30 on Wednesday night, rumors circulated among the community organizers that the eviction was almost a certainty. In the end, José only managed to leave with 12 of his neighbors, while the rest chose to stay and resist.

The violent raid that started at 5:30 the next morning involved 4,000 police officers. They burned the shacks where families had been living for almost four months. Sergio Berni, the province’s Minister of Security, choreographed and guided the aggressive response to the conflict. Berni is known for zealously implementing zero-tolerance policies and strict punishment. He organized the eviction with pride, vindicating the police force, and claiming responsibility for what he thought was a successful protection of private property rights. While human rights organizations condemned the unnecessary violence used to evict the remaining families, Berni praised his work in a series of tweets in the following days.

Roxana Fernández, a member of the Lawyer’s Guild (Gremial de Abogadxs), accompanied the claim for the Guernica occupation with her association. She was there as the families were evicted. She was tear-gassed, her glasses were broken, and she saw how the police, even when the land was cleared, kept chasing people who were fleeing.

“It was a cruel raid,” she said. “They flaunted their power and kept attacking 10 blocks away from the occupation, while the neighbors were asking them to stop shooting rubber bullets as it was early morning and many were leaving their houses to go to work.” The repression continued for many hours on the blocks of Guernica. Almost 40 men and women were detained. All of them were released shortly after.

Days after the raid, José’s cell phone keeps ringing and many organizations argue the eviction was illegal. The local government, although it keeps working with the evicted families, has chosen to publicly blame left-wing groups for how the situation unraveled. There are still no valid documents that confirm the domain of the land where the occupation emerged, only what the lawyer Fernández defines as “papelitos,” inconsequential papers, none of which fulfill the legal procedures to affirm ownership: a proper registration signed by a scribe.

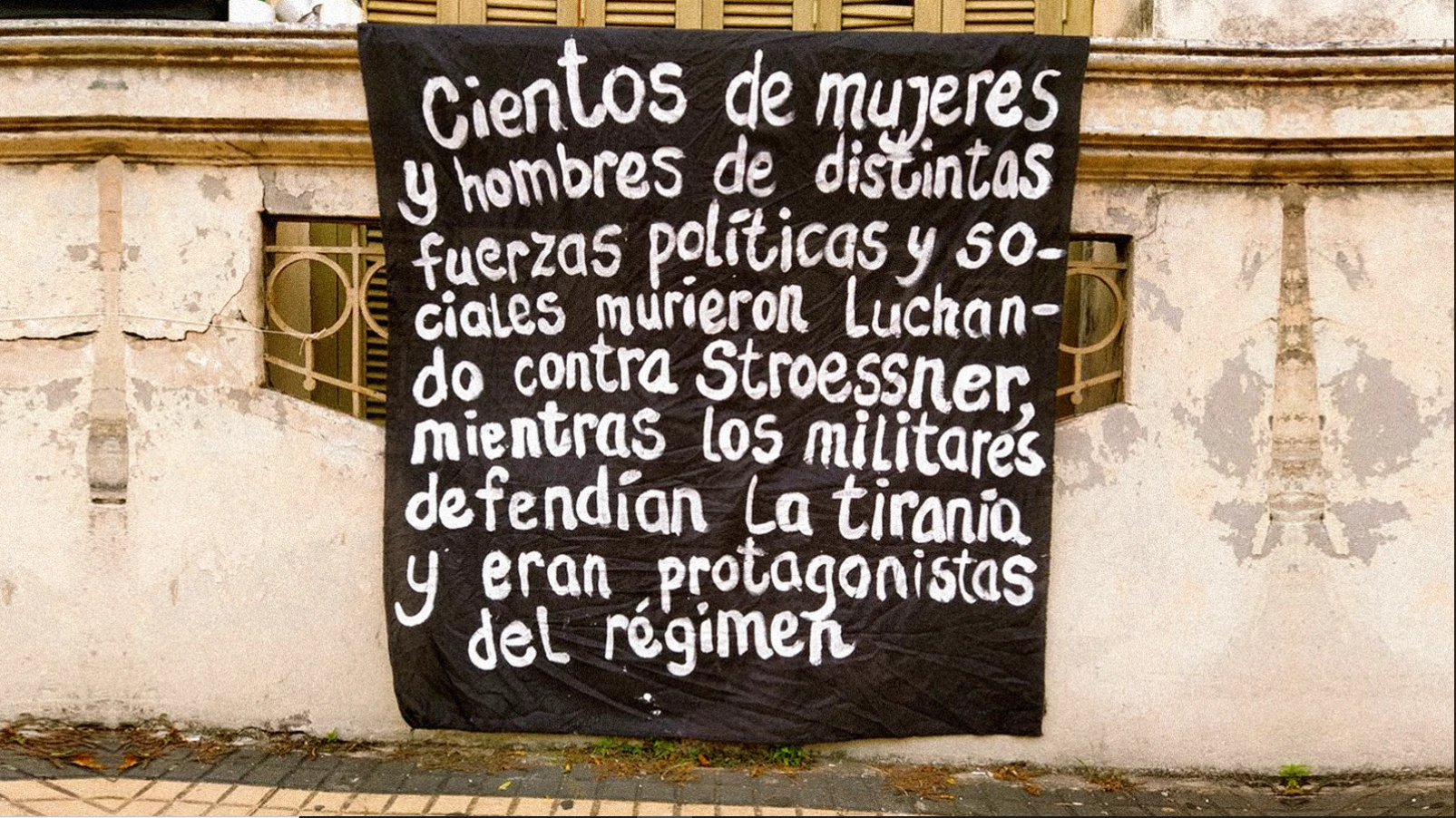

The Political Investigation Team (Equipo de Investigación Política, EDIPO) published a thread showing that one of the land owners, a company called Bellaco S.A., obtained the land through an adjudication in the last months of the military dictatorship, in 1983. This finding shows the close links between private property and violence in contemporary Argentina.

Guernica is just another example of the power imbalance that is visible throughout the country’s history. The land was cleared, but Argentines continue waiting for a decisive solution to the housing problem.

Survivors Recount Sexual Violence During Paraguay Dictatorship

This story was originally published by VICE en Español, and is translated to English for the first time on Latin Dispatch.

Trigger warning: This article includes references to sexual violence and child sexual abuse.

BUENOS AIRES—Coronel Pedro Julián Miers, commander of the Presidential Guard Regiment in Nueva Italia, Paraguay always called Julia Ozorio Gamecho “Pulgita,” or the Little Flea. He used this nickname for two years while he held her captive in the Laurelty estate. During the dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay, from 1954 to 1989, Laurelty was one of five sites where girls and women were sexually exploited, enslaved, and tortured.

Julia was 12 on February 4, 1968, when Coronel Miers kidnapped her and took her to Laurelty. According to her testimony and that of several others, Miers kept girls enslaved for military officials. Her captivity lasted until March 10, 1970. Today, speaking from her home in Buenos Aires, where she has lived for more than 40 years, she emphasizes one thing: “They keep pursuing me.”

Unlike many other countries of the Southern Cone, Paraguay did not have a process of historical memory and reconciliation after the end of the dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner. This goes beyond juridical processes to address the profound, cultural impacts of dictatorship. Paraguay abandoned the possibility of constructing social memory, allowing the sexual and racist crimes committed by members of the regime to be forgotten. Many members of the military dictatorship died without punishment, some of them remembered as heroes. The dictatorship was especially brutal against the Guaraní people and campesino organizations, who conformed the Agrarian League, one of the strongest resistance groups to the regime. The crimes that Stroessner and his henchmen committed at the estates in Asunción must be viewed as state-sanctioned misogyny and racism.

Julia Ozorio Gamecho, like many of the girls, was kidnapped near her home in Nueva Italia, a city close to the capital. “We arrived and there were soldiers and civilians guarding the place,” she says. “When I got there, I threatened to escape. But [Miers] stopped me and said in his military voice, ‘Stop, Pulgita. There is no exit here. So, don’t even try to escape.’”

Forty years after her kidnapping, in 2008, Julia published a book called “Una rosa y mil soldados.” The book relates her life history. Even though Julia gave testimony to the Human Rights Prosecutor’s Office in 2008, Miers died in impunity. The book was a way to share her testimony with whomever wanted to listen. She wrote that Miers visited the estate about twice a month. The rest of the time officers of lower ranks lived at the house. She saw many other girls pass through. She said that most of the Indigenous girls who were kidnapped were later killed. Julia’s testimony is one of the few that informs our understanding of the system of sexual violence that operated under the Stroessner government.

One night in 1975, Malena Ashwell, member of a well-known diplomatic family, was having dinner with her husband, a naval officer, at the house of one of his superiors. Neighbors called them over to their house, where they had found the bodies of three girls, between eight and nine years old, on a pile of sand. They had signs of sexual abuse. Ashwell’s life changed that day: she began to try and call attention to the situation any way she could, including telling the story to The Washington Post using a pseudonym. But the regime persecuted her, eventually throwing her in prison. While detained, she was tortured and attempted suicide. Finally, her father was able to arrange her release on the condition that she would go to the United States and not return to Paraguay.

What Ashwell witnessed took place at a house in the Sajonia neighborhood of Asunción, where Coronel Perrier kept girls he bought from poor, campesino families. The testimony of one anonymous victim, in the “Calle de Silencio” documentary (2017), revealed more details about the house. The girl was sold when she was 13, for 31,000 guaraníes (less than 5 USD) by her mother. A woman took her to the home of Colonel Perrier, who greeted her, and they talked for three hours. Then she was lead to a bedroom. The sexual slavery continued. Every so often they would allow her to go to her family for a night, and then would come looking for her the next day. “I lived waiting for them to capture me,” she says in the documentary. “And there I met the president.”

Stroessner visited the residence in Sajonia. Other girls were known to be held captive in a house in Ití Enramada, a neighborhood in the south of Asunción. “The president would visit and would drink tereré [a type of yerba mate], and sometimes he would have lunch,” the victim remembers. Neighbors would see him arrive at night once or twice a week, driving his own car, and parking at the house.

Many girls died at the Sajonia house and their burial sites are unknown. The identity of the three girls who Malena Ashwell saw was never confirmed, nor their final resting place.

Feminist sociologist Kathleen Barry warned in her 1979 book Female Sexual Slavery that the Stroessner government facilitated sexual exploitation of campesino girls domestically and as part of international trafficking networks. “The enslavement of girls and women in Paraguay can be traced to the corrupt military dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner,” Barry wrote. “Before his coup, there was only one brothel in all of Asunción.”

The consequences of naturalizing sexual exploitation persist to this day. According to the General Department of Statistics and Censuses, almost 50,000 girls and boys in Paraguay live in conditions of “criadazgo,” in which parents give their children to families of a higher economic status who, in exchange for education and food, make them do domestic labor. These children’s confinement often leads to physical and sexual abuse. The stories of youth abused in the criadazgo system are not so different from the stories of the girls held captive during the Stroessner regime.

Julia Ozorio says that the genealogy of what she lived through and what children live through today is the same. “It is with that mentality that the dictatorship controlled the people in the countryside and elsewhere. It shouldn’t be like this, but it is. The violence that I suffered and the violence against the criadazgo is racist. And the country continues to be racist.”

While in Argentina the objective of the dictatorship was to eliminate leftist and Peronist political organizations, in Paraguay, the regime targeted the Guaraní and Indigenous culture more generally. According to the Commission for Truth and Justice, acts of sexual violence targeting girls usually took place during military and police operations in campesino communities. 37% of girl in the Commission’s survey reported suffering these abuses, of which 85.2% took place in departments in the country’s interior, with majority Guaraní populations.

During her captivity Julia remembers that a German doctor appeared, who studied several of the girls’ bodies. “It was Mengele. Now I know,” she says, referring to the Nazi doctor who spent time in South America. “When a girl in fifth grade is alert, intelligent, knew how to write, he realized it. I wrote, I wrote poems and short things in the sand. And he said: this girl is going to be smart. He injected me, gave me vaccines, to fatten me up and later sell me.”

There is not specific proof that Josef Megele, the Nazi doctor who is attributed with coming up with the gas chambers, visited the houses. But there are studies showing that the regime received him in Paraguay for a period of time between the fall of Perón in Argentina in 1955, and his death in Brazil in 1979. Megele is known to have been obsessed with the bodies of girls and young people with certain physical characteristics. In his experiments on humans, he killed hundreds of people, in addition to the crimes he committed during the Nazi regime.

Julia Ozorio Gamecho’s story opened the door for more documentation of how the violence of the dictatorship persists in different forms today. Few women chose to speak up publicly about their experiences. But Julia is persistent, and she maintains a network with the women who have shared their stories with her.

“Many girls were sold during my time,” she says. “I remember names. Many of them have written to me, including from other countries where they were sold off. I have told them, ‘I will be your witness.’ I named them in my testimony. Even though nothing has come of it.”

Despite the torture that Julia suffered as a young girl, and the violence that was never recognized by her country people, on the other end of the phone she sounds animated when asked about her story. She repeats that she wants is for all of it to be known. In Argentina she learned that talking is the best antidote against forgetting.

“I spoke out because I wanted to help all the women who were like me,” she says. “We cannot continue holding this story without talking about it. Every story written with blood must be told, so it does not happen again. We have to let go of the monster inside us. Why continue crying? We didn’t invent our stories. We were just girls.”

In Argentina, the Next Generation Finds Its Voice

This article is republished from NACLA.

BUENOS AIRES—“How scared you are of a girl, you chicken shits,” tweeted Ofelia Fernández the day her trolls took it to a new level. It was November 2019, and she had just been elected as the youngest lawmaker in Latin America as a member of the Buenos Aires City Legislature. At only 19 years old, she won a seat in the local capital with the Frente de Todos party—the same that took the Alberto Fernández-Cristina Kirchner formula to the presidency.

By the time she wrote the tweet, Ofelia had been popular in politics and social media for over a year, but the attacks that week had become personal: They were aimed against her mother, Eva Mosso, alleging she was involved in state corruption.

“I got into this knowing it’d be tough but not this violent. It wasn’t enough to call me a parasite and lie about me, but now you’re using the most basic card: corruption,” she continued on her Twitter thread. “And because you can’t call a 19-year-old crooked, you mess with my mother.”

Internet trolls had been accusing Ofelia’s mother of being a part of the alleged Ruta del dinero K (K’s money route), which is how the media refers to the alleged corruption committed by el kirchnerismo, the political movement built by former presidents Néstor and Cristina Kirchner. Courts dismissed most of these accusations, and there was no evidence nor real complaints that had been filed against Ofelia’s mother. Once again, internet trolls—mainly coming from pro-life organizations and right-wing parties—created the viral campaign to undermine Ofelia’s legitimacy. That afternoon, when Ofelia finally lost her patience, she called the trolls “basic and perverse.”

It wasn’t the first time her detractors wielded lies against her on social media, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last: fake news, misogynist insults, and troll attacks against women in politics in Argentina are systematic and grow every day. Still, Ofelia is learning how to fight back.

What We Call Political Violence

Argentina became the epicenter of the international feminist agenda because of the massive reach of its #NiUnaMenos and reproductive rights movements. Launched in 2016, the Ni Una Menos campaign and march extended worldwide. Then, in 2018, three million people took to the streets to pressure lawmakers to pass the abortion bill, which spurred debates about women’s rights globally. In the 2019 election campaign, gender-based violence was a central topic on many progressive candidates’ agendas.

Due to these campaigns, lawmakers added political violence to the Law for the Integral Protection of Women (Law 26.485) at the end of last year, expanding its definition of gender-based. The law now recognizes and punishes conduct that aims to undermine the political rights of women.

A study by the Equipo Latinoamericano de Justicia y Género (ELA) found that women experience political violence as elected officers, candidates, and activists, underlining the need for an “intersectional approach” to political rights.

“What we call ‘social media violence’ are the violent acts mediated by technologies. These acts can cause damage to the status of women in politics or even discourage them from getting involved in politics. The most extreme cases lead to physical and sexual violence,” said Ximena Cardoso, who was part of an investigation that the ELA team developed over the last year around the subject of political gender-based violence on social media. Political violence on social media is empowered by the anonymity that the internet provides, guaranteeing impunity. “People don’t say these things to my face,” Ofelia added.

Physical appearance is habitually the basis for attacks against women in leadership positions. “They try to force you out of the political conversation by concentrating on your looks, your wages, your clothes,” said Ofelia. “There are hardly any moments in which hostility is aimed against a solid idea or something I said: It’s not an ideological conflict—it’s just obvious violence.”

Expanding the Margins

In 2018, before the youth climate movement Fridays for Future created international networks of young activists, Ofelia was standing in front of parliamentary representatives in the debate for the abortion bill. She had just finished school at Escuela Carlos Pellegrini, one of the few secondary schools under the administration of the University of Buenos Aires, where she began her activist career and served as student union president. “El Pelle” is the type of school that produces politicians, intellectuals, and national artists. The video of Ofelia speaking to parliamentary leaders during the debate went viral. It was the first time her argumentation skills would become a social media sensation.

Ofelia started getting invited to TV shows, progressive radio programs, queer parties with popular trap artists—most of them her same age—and starred in campaign videos for feminist causes wearing colorful glitter on her face and advocating against conservative ideas. Her image connected not only with the youth, but with feminists of all ages across the country.

With the support of the political leader Juan Grabois and the Patria Grande organization, Ofelia announced her candidacy in June 2019. “I’m here be the voice of the youngest,” she proclaimed. On December 3, she was sworn in, pledging to represent the future of her generation across Latin America.

Earlier this year, U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez faced criticism for wearing designer clothing on a TV appearance. “I rent, I borrow and thrift my clothes,” she tweeted. “Tempted to do a ‘woman on the street’ bit and wait outside the Republican cloakroom to ask each GOP Congressman how much their tailored suits cost.”

“I really look up to AOC and the way she behaves,” said Ofelia. “I’m so inspired by her. She’s older than I am but I feel we are alike in our desire to hack political representation. We are on the same quest: trying to transform the way that we represent ourselves and our people.”

Ofelia remembers finishing TV appearances or public appearances and running to get her phone to search for her name on Twitter. Millennials are used to building their personas with the feedback they get from others on social media—whether it’s how many likes a profile picture gets or how many retweets a statement reaches. Ofelia acknowledges that she sought therapy to learn to pay less attention to the responses she received on Twitter. Studying the backlash other female leaders such as Greta Thunberg or AOC received comforted Ofelia in an odd way. “Alexandria gets personally attacked by the president, he insults her, he is violent against her from the same depoliticized points that I get blindsided from. And she gets through it.”

There are tougher days, Ofelia admits, but starting to ignore the systemic aggression helps: She is fully aware they are not stopping anytime soon.

“My critics used to be much more political. The attacks grew. Every huge step in my political career—such as announcing my candidacy, or winning the election, or assuming office—has had its wave of violence. With every ‘good’ thing that happens to my career, they always have something to overpower it.”

Fake news and Misogyny: the Machista Troll Combo

#HappyBirthdayHomophobe was trending last month on Twitter due to a new campaign against Ofelia, under which people interpreted old posts from her Facebook wall—from when she was 12 years old— as homophobic messages. The day she turned 20, internet trolls focused on installing the trending topic, which they gained successfully. Oftentimes, she can’t just ignore these campaigns.

“I find it important to answer sometimes, to give my perspective on what they are saying about me. They make me a trending topic on Twitter because they say I’m homophobic—well, I’ve got to answer to that and show they’re making it up,” she said. “Sometimes people advise that I just ignore these messages. But it’s not so easy.”

Her insight into how young people choose to handle these aggressions demonstrates the future of politics: Conversations over the internet matter, as our characters are increasingly determined by how we behave—and are received—on social media.

The question behind all of these systemic attacks is, after all, what triggers this seemingly unstoppable violence against a 20-year-old woman and her peers. Ofelia believes it is her ideas, although they are not the target of criticism.

“They’re annoyed because we [feminists] carry an agenda that was never a part of politics before,” she said. And she does not leave her political comrades out of the discussion: She knows that most of the men in her party are also in the process of deconstructing the traditional ways of doing politics in Argentina.

“Being a man and having political power is an extremely privileged position,” she told me. “And now there’s this huge movement demanding they question these privileges by pointing out that they make no sense. It’s a personal contradiction, and it’s really tough.”

As political violence has become a legally punishable form of gender-based violence, progressive female leaders recognize each other and unite against hate speech. And when collective organizing is not enough, Ofelia deals with her stress in the same way any other young woman her age does.

“Whenever I’m about to collapse, I listen to the saddest song I like at the moment to help me cry and liberate some tension,” she said.

Decades After Argentina’s Dictatorship, the Abuelas Continue Reuniting Families

This story was co-published with NACLA.

Due to the coronavirus, this year is the first time since 1983 that the Abuelas and Madres of Plaza de Mayo won’t march on the anniversary of the Argentina’s military dictatorship. Nonetheless, the “Día de la Memoria” will continue and thousands will demand “memory, truth and justice” from their homes. The struggle to hold the military to account for crimes against humanity are a part of Argentinian identity. A group of grandmothers leads the story of that struggle.

It was an atypical grandmother’s birthday. On February 18, Delia Giovanola, who had just turned 94, sang “Feliz Cumpleaños” surrounded by a group of people that included her comrades from Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. She clapped with excitement and, once the song was over, turned to hug her grandson Martín. Even though he is 44, it was just their fourth birthday together. Martín has only been Martín since the day he got the phone call that changed his life.

On October 16, 1976, Stella Maris Montesano, 27, and Jorge Oscar Ogando, 29, were kidnapped by the military. They were taken to the Pozo de Banfield, one of the many centers for clandestine detention that operated under the Argentine military civic dictatorship. The intention was to torture and kill the mostly young detainees in an alleged crusade against the “subversive germ.”

Argentina’s dictatorship took place in the context of systematic extermination of guerrillas and left-wing ideas in many other Latin American countries. Chile, Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay, and other countries had similar dictatorships, gathered under Plan Cóndor, a U.S.-backed campaign that united the military governments through intelligence to detect and suppress any potential opposition to their power. The activists in Argentina were mainly divided in two groups: Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo and Montoneros. After the 1976 coup d’etat, most of them went into hiding and organized in secret.

Stella Maris Montesano and Jorge Oscar Ogando.

During the first years of the military government, their political activity was suppressed and young activists went missing. After democracy was restored in 1983, investigations were opened and society began to find out about the crimes against humanity during the dictatorship. Some of them involved disappearing the bodies in “death flights,” throwing prisoners out of planes into the Río de la Plata.

Argentinian society was paralized and under a state of terror. Human rights organizations were the few who went fearlessly out on the streets to demand information about missing people, led by a group of mothers and grandmothers who were desperately looking for their children and grandchildren. The Abuelas of Plaza de Mayo association continues their search today. They developed scientific methods to identify their grandchildren, and achieved the construction of public policy to search for traces of the violence during the dictatorship.

Families like Martín’s have been reunited through their struggle. Stella Maris, his mother, was eight months pregnant when she was kidnapped. She gave birth to a boy named Martín on December 5, 1976. Shortly after, she was taken to another clandestine center. Both her and her partner Jorge remain disappeared, two of the 30,000 missing people after the genocide.

Juana Elena Arias de Franicevich, a midwife who collaborated with the dictatorship, forged Baby Martín’s birth certificate. She is known to have forged at least 10 other certificates. She died in 1995 and her crimes went unpunished.

The fate of the children born in captivity varied. Many were adopted by military families and grew up in violent and oppressive environments. Others, including Martín, were raised by families who had no clue of their origin. This is why Martín chooses to use the word “adoption” as opposed to “appropriation” when he refers to the family in which he grew up.

Martín was raised as Diego and lived a healthy and happy youth. When he was 22, he moved to Miami in search of new opportunities, where he made his career selling electronic devices. He got married and had two daughters, who were 11 and seven when he found out the truth about his identity.

Martín, unlike many of the almost 130 adults who have had their identity restored, showed up intentionally to find out if he was a nieto. Most people his age knew by heart the campaign of the Abuelas that ran on TV, radio and newspapers during their youth: “If you were born between 1976 and 1983 and have any doubts about your identity, call.”

Martín’s adoptive father was open about the fact that he was not his biological father. Martín began actively searching for his true identity after his adoptive parents died. That year, 2015, he visited the Buenos Aires office of the Abuelas. A few days later, he was already back in Miami getting the DNA test at the consulate.

“I was determined to find out the truth about my identity,” he recalls. His sample was sent to the National DNA Data Bank (BNDG), the archive of genetic material extracted from relatives of disappeared people.

Seven months later, he was at his office in Miami when his phone rang. It was Claudia Carlotto, head of the National Commission for the Right to Identity (CONADI).

“Sit down,” Claudia said to Martín. “I’ve got some news.” Claudia informed him that his DNA tests came back positive, and that he was the son of Stella Maris and Oscar.

“And you have a grandmother,” she added. “She’s been searching for you like crazy for 39 years.”

Finding Martín

Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo are now a worldwide symbol, but their struggle went unrecognized for many years. Delia was one of the 12 founders of the organization and searched relentlessly for over 500 missing babies born in captivity. She still does, as 400 remain missing. Martín was the grandchild number 118 that the Abuelas found with support from the CONADI and the National Bank of Genetic Data.

When she found out about Martín, Delia was in a car heading to a conference about the search for the missing grandchildren. She received a phone call from Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo asking her to come to a meeting. She refused; Delia never misses commitments. Back at the office, they asked the organizers of the conference to tell Delia it was cancelled. After they did, Delia agreed to go to the Abuelas office, with no clue of the news she was about to receive.

The three words that she’d been waiting for came from the president of the Abuelas, Estela de Carlotto:

“We found Martín.”

Delia broke into what she describes as a mix of laughter, tears, and shrieks. Her joy grew when Claudia added that he wanted to talk to her on the phone. This was a first: Grandchildren usually take their time before contacting their families of origin. Martín was enthusiastic about hearing the voice of the woman who had searched for him for almost 40 years.

“Hola, Martín! Martín!”

“Hola…You are calling me Martín, but my name is Diego…”

Martín was hesitant. He was sitting down, and the surroundings in his office stood still while his life transformed with each passing second. Delia told him that she had searched for him under the name of Martín—that it was the name that his mother had chosen for him. And again, he absorbed the new information. He accepted being called Martín.

Delia told him she was very modern and used social media and Whatsapp daily, so they could connect easily. The subsequent calls were through Skype, the platform in which they “met” officially. He travelled to Argentina a few weeks later, in December. He visited with his now ex-wife and two daughters.

“I had told my grandma I would visit after lunch,” Martín says. “But we arrived a bit later. That’s what she told me when she saw me: that I was late!”

Martín and Delia.

A New Start

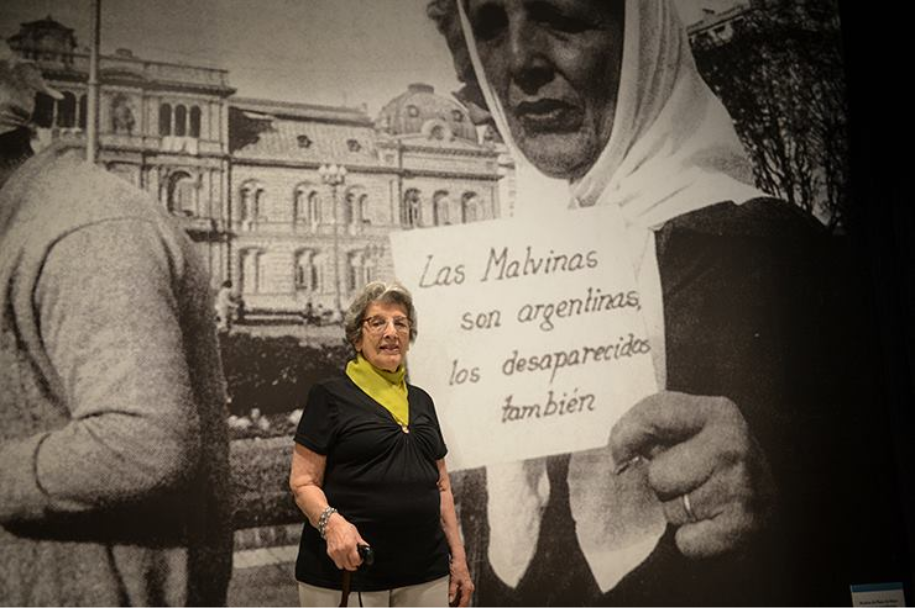

Delia has a reputation for fearlessness. During the beginning of the Falklands War in 1982 that Delia seized on the presence of international media in the country, and held a sign in front of the news cameras that read, “Malvinas are Argentinian, the disappeared too.” The courage of the Abuelas was a threat to the military government, and many of them were kidnapped and disappeared. Nothing stopped them.

She was grandmother to a girl, too. Virginia was Martín’s older sister. When Jorge Oscar and Stella Maris were kidnapped, Delia took her in and raised her. Virginia joined the struggle of the Abuelas to find the truth about what had happened to her parents and to find her little brother. But the pain was unbearable and Virginia died by suicide in 2011. Delia recalls this as one of the hardest moments of her life.

Now, Martín shares her family history. He says, “This is what came with my search: my history. It’s a very hard truth.” Still, he is happy he found it. After finding out about his true identity, Martín started traveling back to Buenos Aires every month.

“Having been in the US for a long time, I felt uprooted from Buenos Aires for the first time after 2015,” he remembers. His work allows him to spend time both in Buenos Aires and Miami, where his daughters still live.

Being part of the Latinx diaspora in Florida, Martín faced a double challenge: He had to adapt to his new identity in a different country that did not share the consciousness of what it means to be a grandson to Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. Luckily, Martín is mainly surrounded by Latinx friends and colleagues, making it easier to share his story. Before the DNA result, he had barely spoken about the fact that he knew he was adopted. Only his ex-wife knew about his doubts. Now, in spite of keeping Diego as his legal name in the US, he is open about his story.

The life of the grandchildren change swiftly when their identities are restored. Many re-do their lives completely, change careers, separate from lifelong partners, and move to different cities. One thing that Martín shares with many of the 128 restored grandchildren is the commitment to their new families and particularly to the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. With the aging of the Abuelas, the grandchildren know they will be the ones to carry out the project in the future. And the search will grow even more complex. The grandmothers started looking for children, then for young men and women. Now, they are searching for mature adults and even great-grandchildren.

Martín is aware of the privilege he had by being able to connect with his grandmother and finding her healthy enough to share adventures. Delia was revitalized when she found him. Each time he visits, she makes plans for both of them, takes him to different conferences, and expects him to spend time with her in her house in Villa Ballester, in the northern suburbs of Buenos Aires. He has his own room: She moved into a smaller bedroom so that he could be comfortable. In spite of being part of a league of exceptional and now world-famous grandmothers, Delia is a typical granny. She even resists cursing in front of him.

Every Día de la Memoria gathers hundreds of thousands marching across the country under the slogan “memory, truth and justice.” These three words have not only defined the generation of young people that lived under terror during those years but have also constituted a social identity that shapes today’s youth.

After singing happy birthday, after Delia hugged Martín for several minutes—something she had been dreaming about for 39 years—Estela de Carlotto invited some school students who were visiting the Association for the first time to share cake and wish Delia a happy birthday. As she let them in, she warned them:

“You are now in the house of Las Abuelas, where there is no sorrow. Only lucha.”

And the Abuelas will never lose their perseverance: The struggle will go on for all of them until all of their grandchildren are reunited with their families.

Lucía Cholakian Herrera is a freelance journalist based in Buenos Aires. She reports human rights stories, feminist struggles and investigates identity in contemporary Latin America. She has won a Premio TEA for her coverage on sexual assault trials in Buenos Aires.