Deaths of Elders to COVID-19 Cause Irreparable Loss in Amazon Communities

This article is re-published from Mongabay under Creative Commons.

Alessandra Korap’s voice breaks when she lists five Munduruku indigenous elders living along the Tapajós River, a tributary of the Amazon. Between 9 May and 2 June, Angélico Yori (aged 76), Raimundo Dace (70), Jerônimo Manhuary (86), Vicente Saw Munduruku (71), and Amâncio Ikon Munduruku (59) died — all victims of COVID-19.

Since then another three have passed, including Acelino Dace (77). The loss in a matter of days of eight elders — leaders and keepers of the Munduruku culture — is a huge blow for a people only numbering around 14,000.

Amâncio Ikon Munduruku was a teacher and respected leader. He played a vital role in the Munduruku’s momentous decision — in the face of decades of delay by Brazil’s government — to mark out the boundaries of their own territory beside the Tapajós River. This show of indigenous strength was crucial in the government’s 2016 decision to abandon plans to build the São Luiz do Tapajós hydroelectric mega-dam, which would have flooded part of the now fully measured Munduruku territory.

While grieving the loss of dearly loved elders, the Munduruku are now also coping with the irreparable loss to their culture. “Every time an elder dies, a library is burnt,” Bruna Rocha, a lecturer in archaeology at the Federal University of Western Pará, tells Mongabay. She is quoting Amadou Hampaté Bâ, a renowned intellectual from Mali in Africa, but she says, the quote applies equally to the traditional people of the Amazon forest, whether indigenous, riverine or quilombolas (descendants of run-away slaves).

Munduruku indigenous elder Acelino Dace died of COVID-19 at age 77 on 3 June. Image courtesy of El Pais.

“Besides being knowledge repositories on the environment, history, territory, production of specific artefacts and medicines, these elders provide political and spiritual guidance, being fundamental in the struggle for territorial recognition. They remind their peoples of who they are in a fast-changing world,” Rocha says. “The sudden death of a number of elders from the same community could be compared to torching national museums, libraries and parliaments all at the same time.”

COVID-19 killing the most vulnerable

Fiona Watson, from Survival International, an NGO that works with indigenous peoples, told Mongabay that COVID-19 is awakening painful memories: “Many elders recall vividly the devastating epidemics spread by government indigenous agencies and land grabbers, loggers, ranchers, and miners in the 1970s and 1980s,” during Brazil’s military dictatorship. “It was not uncommon [then] for 50%, even 90%. of a tribe to be wiped out within the first year of contact.”

A particularly tragic case: the Matis, living in the Javari River Valley in the far western Amazon basin, in Amazonas state near the frontier with Peru. Numbering several hundred when first contacted in the late 1970s, their population fell to just 87 by 1983, as waves of epidemics raged through their isolated villages, killing mainly old people and children.

The consequences of the current pandemic may not be as serious because its overall mortality rate (now at around 1%) does not seem as high, but that estimate remains uncertain — no one yet knows how this pandemic will impact different ethnic and racial groups, not to mention its impact in remote settlements almost completely without modern health facilities.

However, according to evidence collected so far, COVID-19 may be far more dangerous for indigenous and black Brazilians than for white Brazilians. One study by Fiocruz, the health ministry’s internationally renowned institute of health science and technology, suggests that the death rate among hospitalized Indians is 48% compared with 28% for whites, 36% for black Brazilians and 40% for Brazilians of mixed race.

Lúcia Andrade, from the NGO, Comissão Pro-Indio, believes that — as around the world — poor and disempowered groups are being disproportionately affected. “There is a race, ethnicity and social class bias in the tragic deaths from the pandemic,” she told Mongabay.

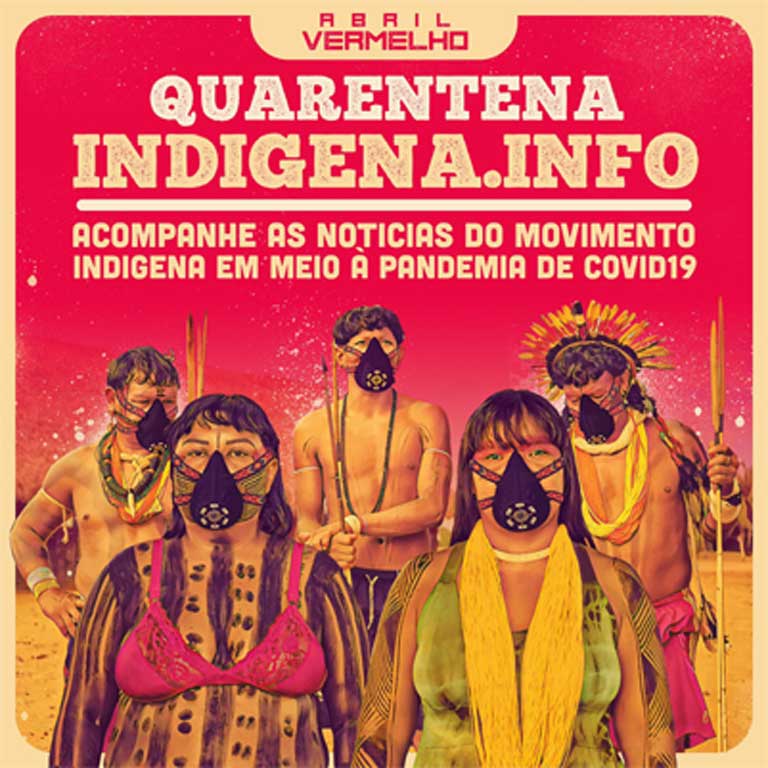

Indigenous groups mobilize in “Red April” to keep forest peoples informed about the pandemic. Image courtesy APIB.

As the pandemic spreads, authorities seem to dither

At this point, it is impossible to accurately gauge just how rapidly COVID-19 is spreading among indigenous groups, says Angela Kaxuyana, a member of the executive council of COIAB (the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations in the Brazilian Amazon), active in the Amazon region’s nine states.

According to APIB (Association of Indigenous People in Brazil), a network of indigenous organisations, 218 indigenous people had died and 2,642 had been infected by 7 June. But, she says, widespread under-reporting, due the remoteness of many territories, and frequent misdiagnosis mean that the real situation may be much worse. “We fear that the real figure for infections may be at least three times greater,” she told Mongabay.

Angela berates the response from authorities: “The government is only beginning to take action [in the Amazon] and what they are doing is quite inadequate.”

She warns: “If we go on at this rate, some indigenous peoples will be wiped out.”

Some peoples are being more seriously affected than others. Like the Munduruku, the Kokama, who live along the Solimões River, where Brazil, Peru and Colombia meet, are reeling from the pandemic’s impact. The Kokama were the first people to have a confirmed COVID-19 death in an indigenous village — now at least 51 of their people have died from the disease.

Ageu Lobo Pereira, President of the Association of Montanha and Mangabal Communities, addressing a meeting in Trinidad, Bolivia in 2017. Both Montanha and Mangabal are threatened by COVID-19. Image courtesy of Vinicius Honorato.

Kokama leaders warned authorities they were particularly vulnerable because of the large number of people coming and going on the frontier region. Yet, they say, few measures were taken: “We are afflicted and desperate… and indignant at the negligence, disregard and omission of public powers at the federal, state and municipal levels.”

The Xavante people in the Marãiwatséde Indigenous Territory in eastern Mato Grosso state believes authorities have put them at risk due to official blunders. On 28 May health officials purposely returned a COVID-19 infected man back to Marãiwatséde village. He was told to live in “domestic isolation,” although this is virtually impossible in a settlement where 30 people or more of all ages live together in small houses. Cultural Survival, an NGO working with indigenous people, dubbed this action, “a genocidal move that exposes an entire A’uwẽ-Xavante community to COVID-19.”

Pandemic poised at Yanomami Park and Javari Valley

The coronavirus has also reached Brazil’s two largest reserves — the Yanomami Indigenous Territory (9.6 million hectares/37,000 square miles) in Roraima and Amazonas states, and the Javari Valley Indigenous Territory (8.5 million hectares/32,800 square miles) in Amazonas state. Those two territories are home to most of Brazil’s isolated and uncontacted Indians.

The Yanomami Territory is under severe threat due to the presence of some 20,000 wildcat gold miners. APIB says six Yanomami have already died of the virus and dozens more are infected — but far worse is expected.

The Yanomami are “the most vulnerable people in the whole of the Brazilian Amazon to the pandemic,” according to a recent study produced jointly by the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) and the Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA), an NGO. The study predicts in a worst case scenario that, if urgent action is not taken, 40% all of the almost 14,000 Yanomami living less than five kilometers from the miners’ illegal settlements, could be infected. While it is difficult to make accurate predictions, given the scant knowledge about indigenous vulnerability to the disease, the study predicts that in this case between 207 and 896 Yanomami could die, making this indigenous group one of the world’s worst affected communities.

The Yanomami are mobilizing to prevent this outcome, if possible. According to Dario Yanomami, from the Hutukara Yanomami Association: “Our shamans are working non-stop to counter this xawara (epidemic). We will fight and resist.” The Yanomami have organized a campaign, supported by various national and international organizations, including ISA and Survival International, called ForaGarimpoForaCovid (MinersOutCovidOut). It aims to put pressure on the Brazilian authorities to expel the illegal miners. However, critics wonder if the Bolsonaro government, with its continued denial of the pandemic and its anti-indigenous stance, will respond.

The Javari Valley Indigenous Territory is also under enormous threat, though reporting from there is much harder to obtain because many indigenous people live in isolated groups fleeing contact with the outside world. Fears are that the virus will spread to those groups via the sporadic contacts they maintain with neighbouring groups.

On 7 June it was reported that seven Indians and four health agents in the Javari Valley had been infected with the virus. The Union of the Indigenous Peoples of Javari River Valley (UNIVAJA) has sent out an SOS, urgently calling for help from the government and non-governmental organizations.

“Now that the virus has reached our community, we are afraid of genocide in the Javari River Valley. We will be counting bodies,” said Eliésio Marubo, a lawyer with the Union of the Indigenous Peoples of Javari River Valley (UNIVAJA).

Other indigenous peoples seriously at risk are those living in the remote Tumucumaque Park, located in Brazil’s far north in Amapá and Pará states, a reserve covering 1.7 million hectares (6,563 square miles). Six ethnicities inhabit the park — the Aparai, Kaxuyana, Tiriyó and Wayana, along with two groups of isolated, uncontacted Indians.

According to Angela Kaxuyana, COIAB has worked with the indigenous villages there to help prevent COVID-19 reaching the territory, but the park is located near the Surinam frontier and there is a military post within the territory. “Soldiers travelled to this post, without being tested for the virus and without protective equipment,” she fumes. “They brought in COVID-19.”

Kaxuyana, who comes from the region, says that at least 23 indigenous people are infected already, including a pregnant woman, who has been hospitalized in serious condition. According to her, the first two indigenous cases involved Indians employed by a cleaning company that works for the Air Force running the military base.

Kaxuyana notes that a tiny medical team is trying to deal with the developing crisis. “In practice, the military have abandoned the Indians to their fate. This is criminal activity by the state and they must be held to account,” she says. Kaxuyana is worried that the pandemic will spread further, as those in the affected village have had contact with neighboring villagers.

The Defense Ministry told the Folha de S. Paulo newspaper that “it is not possible to be sure where the contagion in the region came from, but it is very unlikely to have been transmitted by soldiers working for the Brazilian Air Force.” Another version of the story concerning COVID-19’s arrival says that traveling indigenous people were infected while away from the community, and brought the virus back to the Park later.

Quilombolas and riverine communities also hit

As with indigenous reserves, it is difficult to determine the impact of COVID-19 among the quilombos (the land occupied by traditional communities originally set up by runaway slaves), because they have long been neglected by authorities and there is little official record keeping.

“We are invisible,” says Gilvânia Maria da Silva, the co-ordinator of CONAQ (Black, Rural, Quilombola Communities). Because the state has been very slow in recognizing quilombola territories, official statistics have persistently underestimated populations in these communities. Likewise, authorities often fail to register that a person is a quilombola on a death certificate.

To combat what they call “the invisibility of the illness in quilombola territories,” ISA recently joined forces with CONAQ, to set up a new website, called Quilombo sem Covid-19, which registers confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths. So far, the site has registered 353 confirmed cases and 59 deaths, though these numbers are thought to fall well short of the true figures.

Hundreds of thousands of often small Amazon riverine communities are also at risk. What affects them most is the chronic failure by authorities to provide public health and other services. The small communities of Montanha and Mangabal on the Tapajós River are a case in point. Although no definitive tests have been carried out there, COVID-19 is believed to have reached the settlements via a bus driver, who, without tests or protective equipment, was plying the route between the city of Itaituba (population 101,000) and the community.

Ageu Lobo Pereira, the President of the Association of Montanha and Mangabal Communities, told Mongabay that residents see themselves as forgotten “particularly with respect to health and education.” As if to underline that point, Seu Filó, one of the community’s greatest authorities on the local Amazon forest, died on 5 June, not from COVID-19, but from a stroke, which some in the community believe could have been avoided if he had been treated properly for high blood pressure. As elsewhere, COVID-19 detracts from the treatment of other health disorders.

Bruna Rocha calls this is a critical moment: “We can only hope that the overwhelming grief they feel will spur surviving forest peoples on to fight for their rights, to honor the memory of those who have gone,” she says. “We must stand by them in every way possible after the pandemic has passed, whenever that is. But until then, all efforts must be geared to saving lives — in spite of the federal government. Indigenous lives matter.”

For more coverage of the Amazon and COVID-19, visit Mongabay.

Bringing Christ and Coronavirus: Evangelicals to Contact Amazon Indigenous

This article was originally published by Mongabay.

Ethnos360, an evangelical Christian missionary group, is embarking on a controversial new project, just as the coronavirus begins spreading widely in Brazil.

The organization, formerly known internationally as the New Tribes Mission, and based in Sanford, Florida, USA, plans to use a newly purchased aircraft to contact and convert isolated Amazon indigenous groups — even though such contact is banned explicitly by FUNAI, Brazil’s indigenous agency, and implicitly under the nation’s 1988 Constitution.

The fundamentalist Christian group’s venture could also spread dangerous infectious diseases, like COVID-19, to isolated tribes utterly lacking resistance and immunity.

At the end of January, Edward Luz, president of New Tribes Mission of Brazil, announced the acquisition of the “Ethnos360 Aviation R66 helicopter,” able to operate in the remote rainforests of Western Brazil, and he told a small group of Christian evangelicals assembled in Rio de Janeiro, that: “God will do anything to see to it that mankind hears His Word. If a helicopter becomes necessary, He provides it.”

The “mankind” to whom Luz referred includes isolated Amazon indigenous groups. Brazil has 115 confirmed indications of such groups — more than any other country in the world. All but two are in the Amazon biome. Many are concentrated in the west of Brazil near the frontier with Peru, which is the area targeted by Ethnos360Aviation.

Spreading the Word of God, and disease

New Tribes Mission, established in 1942, has a long, checkered history in Brazil. One case concerns its contact with the Zo’é, an isolated indigenous group living in the remote Amazon rainforest of northern Pará state. By 1980, small-scale goldminers and Brazil nut collectors were already gradually penetrating their territory, but the Zo’é fled contact. Then, in 1982, New Tribes Mission learned of the group’s existence and started dropping “presents” from the air on their villages. In 1987, the missionaries established a base camp and airstrip on the edge of the Zo’é territory.

Over the next two years, evangelicals made several forays toward the Zo’é villages, making sporadic contact with the tribe, who, according to the missionaries, remained “restless” and “withdrawn.” The definitive contact came in November 1987, when a group of about 100 Zo’é appeared at the base camp. Communicating through gestures, the missionaries offered gifts, but in turn were handed broken arrows — a clear message that the indigenous delegation wanted the missionaries to leave.

FUNAI learned of these events and forbade the missionaries from installing themselves in the indigenous villages. Instead, missionaries tried to attract the Zo’é to their base outside of indigenous land. According to the Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA), a Brazilian NGO, the missionaries’ objective was to learn the Zo’é language so they could begin the literacy process, translating the Bible and thereby conveying the Word of the Lord to the group.

The Zo’é began to die rapidly from malaria and influenza — diseases to which they lacked Westerners’ resistance. In 1989, FUNAI visited the missionary base and was shocked at the poor state of indigenous health. Relations with the missionaries deteriorated and in 1991 FUNAI took over, forcing New Tribes Mission to leave.

It is estimated that 45 Zo’é died between 1987 and 1991. Their population, which fell to 133 in 1991, is recovering and is estimated at 250 today. But they remain vulnerable as a people to disease and the loss of their ancestral land to invading cattle ranchers and soy growers.

Another notorious outcome of New Tribes Mission’s work in Brazil includes the case of Warren Scott Kennell, who served as one of their missionaries between 2008 and 2011, living with the Katukina in western Amazonas state. Over several years, he built a trusting relationship with girls as young as 12, then sexually abused them. Tipped off about these crimes, U.S. Homeland Security stopped Kennell at the Orlando, Florida International Airport and found he possessed over 940 images of child pornography.

According to prosecutors, Kennell identified himself in one of the photos as the man performing a sex act on a prepubescent girl. “Kennell represents the worst kind of criminal; one that preys on innocent children,” Shane Folden, deputy special agent in charge of the Tampa office of the Department of Homeland Security, said in a statement. In 2014, Kennell was sentenced to 58 years in prison.

A plan whose time has come?

The boldness of Ethnos360’s helicopter-contact and conversion plan may not be as brazen as it first seems. In February, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro administration made a surprise appointment, putting Ricardo Lopez Dias in charge of The Coordination of Isolated and Recently Contacted Indians (CGIIRC), FUNAI’s most sensitive department. Dias, an anthropologist and evangelical, was a missionary for New Tribes Mission for over a decade, doing conversion work.

A New Tribes Mission Cessna 206 operating in Brazil in 2014. “Our people really need the airplane to be able to get technical help, linguistic help, translation help, even church-planting help and advice and encouragement into their tribe from time to time,” said Wonita Werley, spokesperson for NTM Aviation. Image taken from NTM press release.

In 2020, Epoca, the Brazilian news magazine, revealed that, starting in 2017, New Tribes Mission began circulating promotional videos, raising donations to pay for the R66 helicopter. In one clip pilot Jeremiah Diedrich explains why New Tribes Mission wants the aircraft: “This part of western Brazil is listed by Survival International, [an NGO], as having the highest concentration of uncontacted people-groups in the world … It is the darkest, densest, hardest-to-reach place in the whole of South America. This is why we need a helicopter.”

Survival International, itself, is vehemently opposed to the Ethnos360 initiative. Fiona Watson, Advocacy Director of Survival, told Mongabay: “The New Tribes Mission’s plan to use a helicopter to locate uncontacted tribes is dangerous and irresponsible. They clearly have no intention of respecting these indigenous peoples’ clear desire to be left alone. Any attempt to force contact risks infecting them with deadly diseases. The NTM’s appalling history of forced contacts in South America in the last 60 years resulted in the death and destruction of many uncontacted peoples and should serve as a stark warning not to let them anywhere near these vulnerable tribes. The Brazilian government must act now to stop the NTM’s genocidal plans.”

Violating FUNAI policy and international law

If the New Tribes Mission plan goes forward, it will be in open defiance of an official Brazilian policy established three decades ago to respect the wishes of isolated Indians not wanting to be contacted. That policy was adopted by FUNAI after various instances of serious harm brought by forced contact, including the Zo’é case.

New Tribes Mission must certainly know that they will be violating Brazilian policy by using their helicopter to make unsolicited contact. In another video, Ethnos360 Program Manager Joel Rich refers indirectly to the measures taken by the Brazilian authorities to prevent outsiders moving onto land inhabited by uncontacted Indians: “Unfortunately, only a small fraction of travel trips are able to take advantage of [plane travel]. The remainder [of the villages] do not have an air strip because of government restrictions … We need a helicopter.”

FUNAI’s policies do not have the force of law in Brazil. But experts note that the New Tribes Mission contact and conversion plan likely violates the 1988 Brazilian Constitution, which discarded an earlier policy adopted under the nation’s military dictatorship that indigenous people be “assimilated.” Instead, the document gave native peoples the right to be indigenous forever.

The contact plan also violates international treaties to which Brazil is a signatory. The only international instrument to refer specifically to uncontacted indigenous groups is the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted in 2016, of which Brazil is a signatory. It states in Article XXVI:

- Indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation or initial contact have the right to remain in that condition and to live freely and in accordance with their cultures.

- States shall, with the knowledge and participation of indigenous peoples and organizations, adopt appropriate policies and measures to recognize, respect, and protect the lands, territories, environment, and cultures of these peoples as well as their life, and individual and collective integrity.

Brazil also voted in favor of the United Nations Declaration on the Right of Indigenous Peoples in 2007. Although not legally binding, it is a landmark document which sets out some of the highest standards to which governments should adhere to uphold indigenous rights. Self-determination and territorial rights are at its core, while emphasizing that indigenous peoples have the right not to suffer forced assimilation and destruction of their culture.

An uncertain future

Despite the law, it remains questionable as to whether government action against Ethnos360’s activities will be forthcoming. With Bolsonaro’s election, New Tribes Mission may feel that, after years of hostility from anthropologists, the tide has now turned hard in their favor. Bolsonaro is notorious for speaking of indigenous people living in the remote Amazon as animals in a zoo, and even suggesting that “It’s a shame the Brazilian cavalry [wasn’t] as efficient as the Americans, who exterminated the Indians.” Bolsonaro won office with overwhelming backing from Christian evangelicals and has since placed many in positions of power.

The appointment of Dias to FUNAI, say some experts, sends a signal that Brazil could be about to change its long-held policy on non-contact, even though Dias has repeatedly claimed that his past missionary work does not disqualify him from his new duties. “I understand there is a lot of apprehension regarding what the work of missionaries entails,” he said. “I don’t see this as a mission or an opportunity to find new converts. I have no interest in going there with a Bible in hand.”

But indigenous associations and advocates fear that Dias’ record suggests he might not act to stop missionary contact. Dias spent ten years (1997-2007) among the Matsés indigenous group in the Javari Valley of Amazonas state, working as a missionary for New Tribes Mission.

The primary Matsé leader, cacique Waki, told the Folha de S. Paulo newspaper, that he doesn’t want Dias to have a powerful job within FUNAI. “We know Ricardo well. He learnt our language. We don’t want his church here because he doesn’t let me paint my face, he doesn’t let me sniff rapé [a kind of tobacco smoked collectively by men], he doesn’t let me use frog poison [in hunting]. That’s why I don’t want him.”

The Union of the Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley (UNIVAJA), said that they fear “the evil actions of religious proselytism in indigenous land [in the Javari Valley].”

FUNAI’s career employees association recoiled at Dias’ appointment, calling it in an open letter, a dangerous move that will potentially result in “irreparable damage” to vulnerable isolated indigenous groups.

Even though New Tribes Mission recently changed their name, possibly to make a break with their controversial past, the group openly admits that their vision remains the same. Contacting isolated indigenous communities has been the organization’s prime raison d’être since its founding in 1942, when it set out to bring Christianity to the world’s most isolated communities, however difficult or dangerous it is to reach them.

The first issue of NTM’s official magazine, Brown Gold, published in May 1943, summarized their mission: “By unflinching determination we [will] hazard our lives and gamble all for Christ until we have reached the last tribe regardless of where that tribe might be.” Ethnos360 did not respond to Mongabay’s request for an interview.

In its statement, UNIVAJA expressed fear that, under Dias’s leadership, FUNAI’s CGIIRC could become the “spearhead” of an “ethnocidal and genocidal attack.” Ethnocide is defined as the destruction of a people’s culture. Indigenous groups in Brazil report that New Tribes Mission is already on the move; they say that Ethnos360 missionaries arrived in the Deni Indigenous Territory in Acre state in late February.

Human rights organizations warn that the threat to Brazil’s isolated peoples is now escalating. Laura Greenhalgh, executive director of the Arns Commssion, speaking at a March 2020 meeting of the UN Human Rights Council, said that Bolsonaro’s aggressive socio-environmental policies are already putting isolated Indians at risk of “genocide.”

And the dangers are likely only becoming greater as the coronavirus pandemic takes hold in Brazil; the nation currently has 300+ confirmed cases. Bolsonaro, who until recently dismissed the pandemic as a “fantasy,” was reported last week to have tested positive for the virus, then negative, while several of his staff, including his press secretary, have either contracted COVID-19 or are under observation.

Douglas Rodrigues, with the Department of Preventive Medicine at the Federal University of São Paulo, who works with indigenous populations, has urgently warned of the dangers of coronavirus to isolated Indians: “Measles and chicken pox have killed Indians, but the great villains of this story have been respiratory illnesses and coronavirus is one more of these.”

With the rapid spread of COVID-19, Brazil’s under-funded health system will certainly struggle to cope — especially among remote Amazon indigenous peoples who feel deserted by the public health service under Bolsonaro. Isolated indigenous groups, vulnerable to Western diseases, if contacted by Ethnos360, will be at extreme risk.

This article was originally published on Mongabay and is republished here under Creative Commons.