Argentina, Brazil, Dispatches, Southern Cone

Prelude

October 26, 2018 By Santiago O'Donnell

A Guest Opinion

Jorge Rafael Videla didn’t come into power overnight in Argentina, nor did he start disappearing people by accident. It was the result of years of authoritarianism, violence and abuses, of endless acts and omissions, big and small, of frauds, lootings, bombs, plunderings, blows, killings, abuses of power, and various injustices that were never sanctioned in the country, the city, the neighborhood, the factory, the office, the home or the bedroom. They happened during decades, years, months, a day or a second.

Likewise, it is not a coincidence that Jair Bolsonaro is a step away from assuming power in Brazil, nor did this happen overnight. It is, in the short run, the consequence of an institutional coup, a blow to Dilma Rousseff, yes, to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and to the Workers’ Party or PT, also, but above all, a blow to Brazilian democracy. It is a coup that triumphed because a few nostalgics for power smelled blood, because the silent majority consented, and because too few—too weak—resisted.

They are the hatreds, abuses, and humiliations too many people ignore or tolerate, either because it’s convenient or out of fear or comfort.

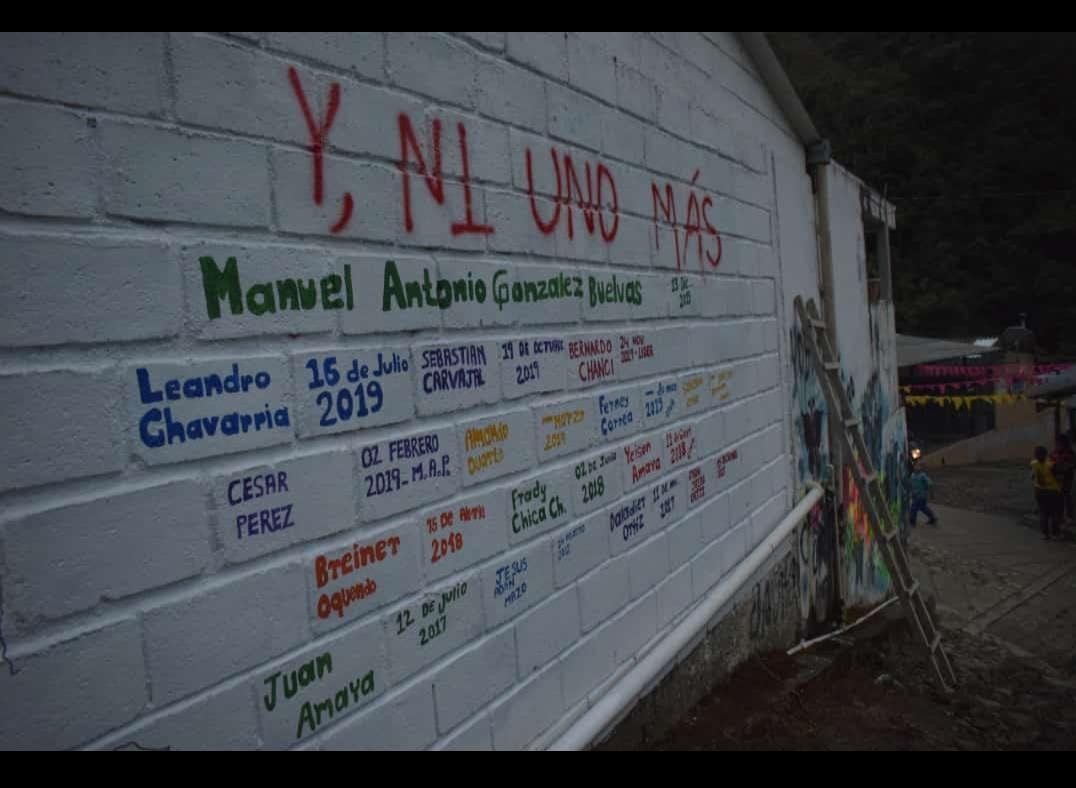

The coup that removed Dilma from power was not a coincidence, nor were her political and economical mistakes its main drivers. What left the door wide open was the implosion of a rotten and corrupt political system that is driven along partisan-business-judicial-media lines. But the tragedy started brewing a long time before. The displacement of the Workers’ Party—that in 12 years pulled 30 million Brazilians out of poverty—and the imprisonment of its leader Lula can only be explained by a long history of racism, classism, misogyny and homophobia. A history like Argentina’s—maybe even more so—fraught with violence, injustices, fears, and small and large despotisms, like the head of plantations in the northeast of Brazil toward the peasant descended from slaves, or the Amazonian miner toward the ancestral aboriginal, or the overseer in the state of Minas Gerais toward the transient laborer, or the plant owner in San Pablo toward the exploited pawn, the new rich in Río de Janeiro toward his favela neighbor, the financial yuppie toward the landless, the bureaucrat toward the homeless, the police officer toward the transvestite, the aggressive husband toward the afflicted mother, the small merchant toward the poor, those who lynched the Venezuelan immigrant last month and those who did nothing to stop it. They are the hatreds, abuses, and humiliations too many people ignore or tolerate, either because it’s convenient or out of fear or comfort.

And almost near the end of the story, a de-facto president shows up. Michael Temer is demonstrably corrupt. He is so despised that he cannot go out in public. He froze health and education budgets to finance a massive military intervention in the showcase-state of Río de Janeiro. This, so uniformed men become accustomed to being given free rein to get involved with narcs and paramilitaries, and not fix anything, not even clarify the execution of Marielle Franco, while, all along, the sick, the illiterate, teachers and nurses feel once again the abandonment of the State.

Now Bolsonaro arrives and with him, hell is just around the corner. Forty-six points against 29 is a lot of advantage. Some will get their hopes up thinking about France in 2002 when Le Pen pere, entered ballottage, when hell was also just around the corner but all of France united and thrashed this candidate in the runoff election. It’s a hopeful thought. But on that occasion, the neo fascist Frenchman sneaked his way to the end, he had come in second after Jacques Chirac in the first round and the global wave of extreme right led by Donald Trump was more science fiction than political science. In turn, Brazil today, is far from unifying against Bolsonaro and his supporters. The evangelicals applaud him, the hard left calls for a blank vote, and the center right vacillates and is silent. I wonder what Fernando Henrique Cardoso, the architect of modern Brazilian democracy, must be thinking. After explicitly supporting the coup, he now murmurs among his close circle, too late and too discreet, that the best thing would be for Fernando Haddad to win in the runoff election.

A miracle à la France will not be what pulls Brazil out of barbarism. A lost democracy is regained doing small and big battles, with protests and songs, through resistance and solidarity, individual and collective gestures, today and always.

The original article was published in Medio Extremo, and was translated from Spanish by Emily Corona. You can read the original version here.

About Santiago O'Donnell

Santiago O'Donnell is the foreign editor at Página 12 newspaper in Argentina and a journalism professor at NYU-Buenos Aires.