This article is co-published with NACLA.

Bolivians went to the polls on March 7, in regional elections postponed a year because of Covid-19. The governing MAS party, under the leadership of President Luis Arce, won governorships in three of Bolivia’s nine departments, or states. The party is headed to a second round in another four departments. The final results have been delayed because of a cyberattack from outside the country on the Electoral Tribunal’s website on March 9.

Santa Cruz, the country’s most populous department, was the only place where the MAS resoundingly lost a governorship. Luis Fernando Camacho won with 63.8 percent of the vote. Far-right Camacho played a pivotal role in the expulsion of ex-President Evo Morales in November 2019. His erstwhile ally, former ex-interim President Jeanine Áñez, ran for governor in her home department of the Beni in the northeast, coming in third.

On the whole, five months after a decisive victory in the presidential election, the MAS results roughly parallel those of the previous regional elections in 2015, when they won six governorships. In the mayoral races, where the MAS was expected to fare poorly because its most loyal political base is rural, they only won in two smaller departmental capitals. A potpourri of local parties built around a particular candidate won in the rest.

The most resounding victory in the mayors’ races–with 68.7 percent of the vote—went to 34-year-old Eva Copa in El Alto, Bolivia’s working class and Indigenous second largest city. Copa had successfully maintained considerable distance from Evo Morales while she was President of the Senate during the Áñez government, leading Morales, head of the MAS electoral campaign to oppose her candidacy. “We hope that her win might inspire a left-wing alternative to the MAS,” said Magali Rocha, a long time MAS supporter who voted for Copa.

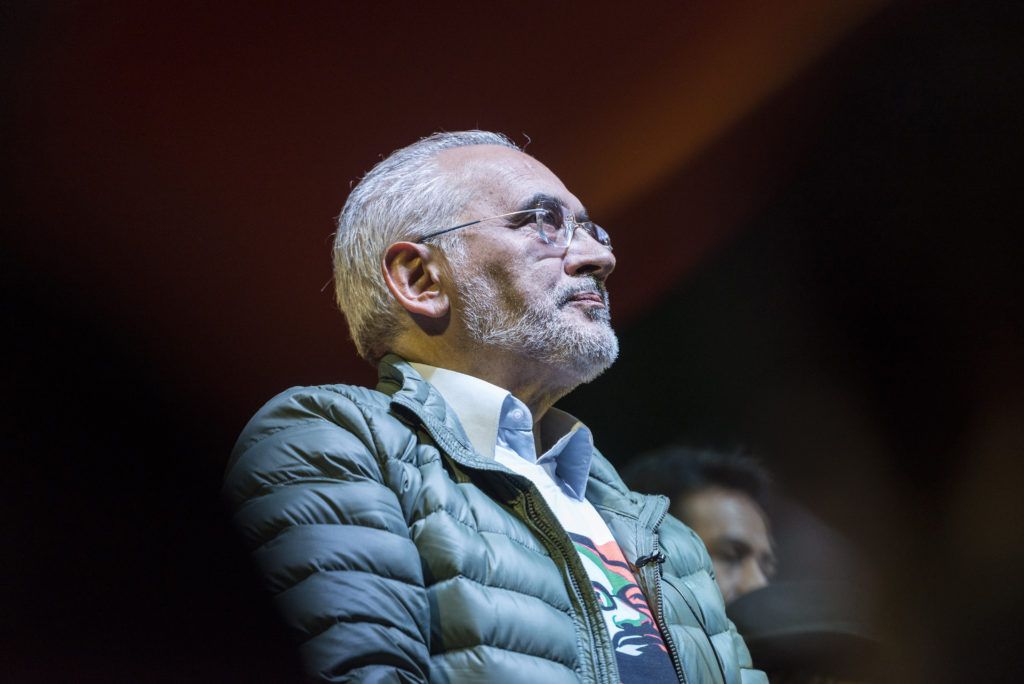

Despite the party’s mixed showing, President Arce performance approval reached 54 percent just before the elections according to a recent poll, only a point shy of the 55 percent of the vote he received in his October national election victory.

Arce’s support reflects public approval of how quickly he swung into action after taking office. Arce’s support reflects public approval of how quickly he swung into action after taking office. He faced both a skyrocketing Covid-19 outbreak and an economic meltdown on his hands. He quickly appointed a younger administration than during his predecessor Evo Morales’ 14 years in office that he calls “a technocracy of the left.” However, only three of the 17 cabinet members are women.

Arce immediately fulfilled his most urgent electoral commitments, delivering financial help to a third of the population, levying a tax on large fortunes, and investigating the accusations of crimes committed by the Áñez government. His team quickly took on broader issues as well, such as land titling and restructuring the judicial system.

A New York Times review of mortality statistics estimated that Bolivia had among the highest excess deaths in the world during the Covid-19 pandemic. With the country at the tail end of the vaccination line, Arce shrewdly allotted $80 million to accelerate obtaining vaccines. 15.8 million vaccines are on order, from Sputnik V, Astra Zeneca, Sinopharm, and an additional 5.1 million through the UN Covax system. Health care personnel were given top priority for inoculation once the vaccines began arriving at the end of January.. The government also quickly acquired 1.6 million Covid tests for a nation-wide free testing campaign.

Bolivia has the world’s highest percentage of people working in the informal sector, who have little choice but to go out to work. The Arce administration has made it clear it has no plans to reverting to the rigid lockdown imposed by Jeanine Áñez in 2020.

A Health Emergency Law passed on February 17 specifies that Covid-19 vaccines are free, international arrivals are required to quarantine for 14 days, and establishes limits on what private clinics can charge for medicine. But a controversial provision allows the Ministry of Health to hire new medical personnel and mandates that health, phone, and internet services cannot be interrupted during a public health crisis.

Even though the draft bill was amended twice with doctors’ input, doctors and health workers immediately went on a two-week strike, which has been extended for another two. They object that the law limits their right to protest and fear that foreign doctors, particularly Cubans, will take their jobs.

In late December, the discovery of a major new national gas field in the southeast by a consortium of multinational hydrocarbons firms working with Bolivia’s state hydrocarbons company YPFB visibly buoyed President Arche. “Our Mother earth (Pachamama) is giving Bolivians a lovely Christmas present,” he said, beaming. The find boosts Bolivia’s proven natural gas reserves that were calculated, in 2018, to last only another 15 years. Most of Bolivia’s gas is sold to Brazil and Argentina.

The shot in the arm was all the more welcome because of how much the economy had tanked in 2020, the worst tumble in 67 years. Gas revenues, the country’s main export, dropped 28 percent, although in January 2021, demand from Argentina bounced back by 58 percent. Financial reserves plunged from $3.77 to $2.14 billion dollars. Government income had already dropped steadily since 2013 when international gas prices plummeted.

In the face of this dismal panorama, Arce turned to the tactics that had proven so effective when he was Minister of the EconomyIn the face of this dismal panorama, Arce turned to the tactics that had proven so effective when he was Minister of the Economy: stimulating internal demand and working towards substituting imports through significant public investment and continued conditional cash transfer payments to the poor. His re-activation plan includes investing $725 million in three months on projects such as increasing natural gas exploration, constructing a zinc foundry in Oruro, and getting the El Mutún iron ore plant up and running after over a decade of suspensions. These plans generally focus on expanding resource extraction, the model the Morales government used to fund social programs and grow the economy, at an enormous cost to Bolivia’s natural environment and lowland Indigenous peoples in particular.

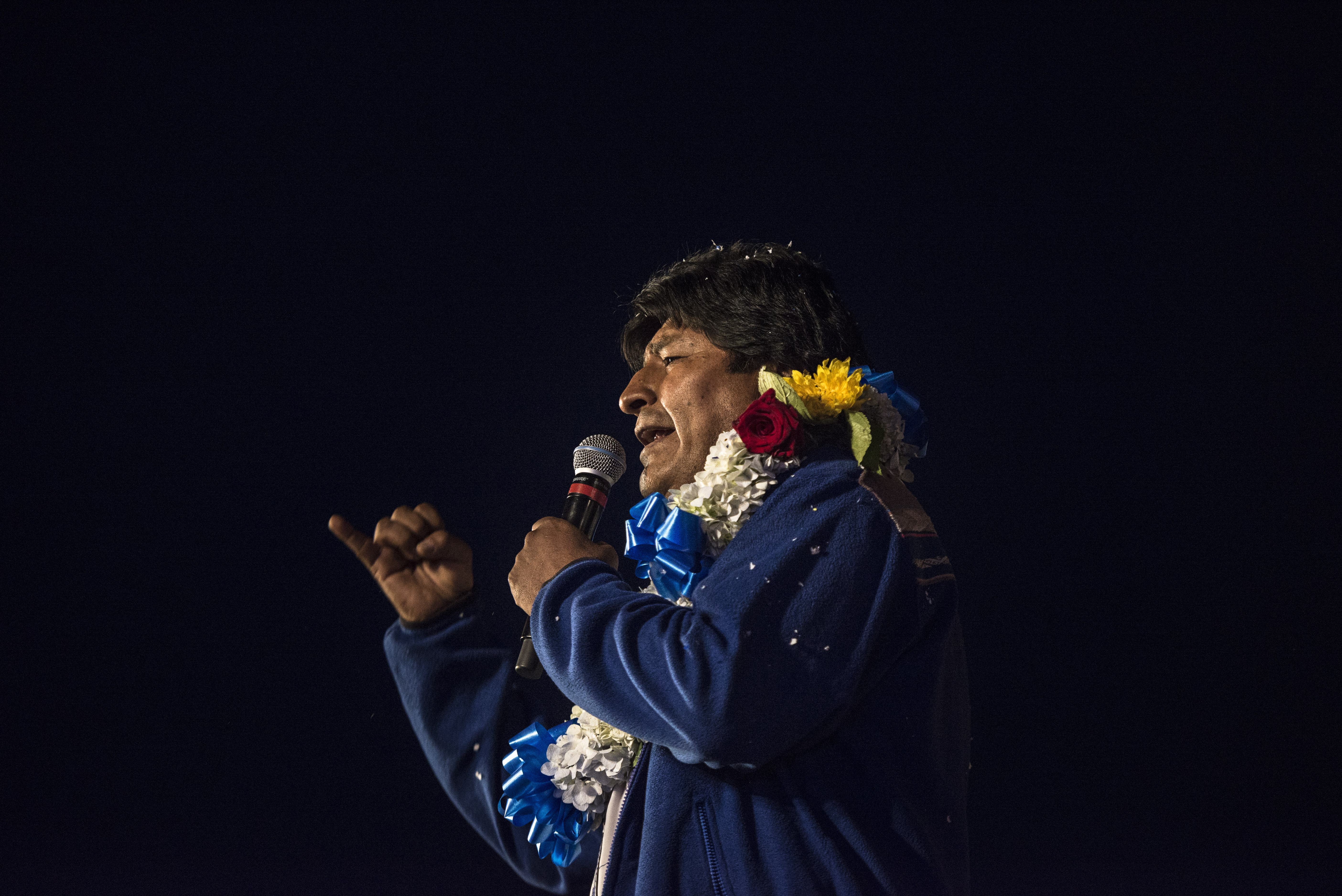

The day after the October 2020 election, Morales returned to Bolivia in a triumphant caravan from his year-long exile in Buenos Aires. When neither Arce nor his Vice-President David Choquehuanca took part, they made it clear they wanted to keep the former leader at a distance. “That was a real surprise,” said MAS supporter, Felipe Guzman, as Morales reached almost mythical status because of his 20-year streak of winning elections.

But while Evo still wields considerable influence, the MAS had re-aligned during year he was gone. A younger and more grassroots wing of the party is pushing for a renovation of leadership and greater internal democracy. MAS party member Juan Carlos Pinto Quintanilla argues, “We must strengthen mid-level leadership in the MAS to succeed. We need many Evos, not just one.”

Arce and Morales appear to have reached an understanding that to date works for them both, with Arce managing the government and Morales as head of the MAS.Arce and Morales appear to have reached an understanding that to date works for them both, with Arce managing the government and Morales as head of the MAS. Lucho’s low-key style contrasts with Evo’s often flamboyant, in-your-face approach and this moderation may serve to ease tensions with centrist elements of the opposition after last year’s extreme polarization.

A significant unknown is whether the new MAS government will prosecute Jeanine Áñez, Arturo Murillo, architect of much of the repression, and other officials for the violence they unleashed during the year their interim government was in power. Murillo has already fled to the United States. After being blocked repeatedly by the Áñez government, in mid-November 2020, the Interamerican Commission on Human Rights sent a delegation to investigate human rights abuses in 2019. “Reconciliation is not just a phrase…We cannot have reconciliation if there is no justice,” said the new Foreign Minister under Arce, Rogelio Mayta, who represented the victims of the 2003 Black October massacres.

One of Arce’s biggest challenges is gaining better control over the police and military after they ran amok, particularly during the beginning of the Áñez government, killing 33 and wounding 804, mostly supporters of the MAS. When the head of the Cochabamba garrison, General Alfredo Cuéllar, was arrested in November for one of two massacres where 10 protestors died, the military high command immediately announced they were “disconcerted” that the General was to be tried in civilian rather than military court. They then highlighted the agreement they had signed with Áñez that protected them from all civil investigations. Arce initially reaffirmed existing military leadership, but in a surprise move late December, he replaced the entire high command.

“The regional elections clarify that the MAS-IPSP remains the only national political force,” said Juan Tellez, MAS mayor a small municipality in southern Potosí. “The right has fractured and atomized and lost any political platform. Its presence, while strong, is only local.” Another takeaway from the results is that with women accounting for only 16 percent of the candidates, the gender parity enshrined in Bolivia’s 2009 constitution remains very much a work in progress.

The unconstitutional process that allowed Evo Morales to run for a fourth term and the equally unconstitutional process that ousted him are still fresh memories in Bolivia. But the diverse political positions, parties, and outcomes in the regional contests confirm that democracy is very much alive.

Linda Farthing has written on Bolivia for The Guardian, The Economist, Al Jazeera and The Nation. Her latest book Coup: A Story of Violence and Resistance in Bolivia, co-authored with Thomas Becker, will be published by Haymarket later this year.