In Rio de Janeiro, Civil Society Fights COVID-19

RIO DE JANEIRO—The coronavirus pandemic has already affected the lives of millions of people around the world. Brazil is no exception. In Rio de Janeiro, the coronavirus pandemic worsened social inequity. Civil society decided to mobilize in different ways to help people in need.

Some people created NGOs, some already existing NGOs intensified activities, others mobilized to gather donations, and a minority donated huge amounts of money to improve the conditions in a state where the government does not assist everyone who needs help.

According to the Donations Monitor, 1,155,772,396 USD was donated in Brazil in response to COVID-19. The Monitor shows that the period between March and mid-May were the most profitable in terms of donations. As of May 10, 950 million donations were received, which shows an increase of 1,077% percent since March 31. From May 31 to July 19, however, this increase was only 4.7 percent. This shows that the number of donations has been stabilizing.

The organization União Rio formed spontaneously in March. According to co-founder Marcella Coelho, the organization was founded through a Whatsapp group with people who wanted to do something for the city of Rio de Janeiro during the pandemic. The first goal was to reform Hospital Universitário Clementino Fraga Filho, a federal hospital in the “marvelous city.”

The organization is divided in two fronts: health and community. The first is responsible for donating funds for buying hospital beds and material for protection, while the latter is to give emergency assistance to families who are struggling financially with the pandemic. Because of its success, União Rio is now present in 20 of 26 Brazilian states.

“We knew how tragic this would be. On the health front, we knew that we wouldn’t have enough beds and protection material for everyone, so that’s where we decided to act,” Coelho says.

União Rio has an active partnership with NGOs in the city of Rio de Janeiro and donates the funds to assist those in need. The organization has already helped 220 families, with the distribution of 3,000 basic kits per day.

“We acted where the government is not present or where it is not capable of helping. We keep in touch with municipal and state leadership to keep track of where our organization should intervene and act, which is mostly in poor neighborhoods,” Coelho says.

Organizations Rise to the Occasion

The state of Rio de Janeiro has 763 favelas, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). At 22 percent of the population, the state of Rio de Janeiro has one with the biggest populations living in favelas in the country.

Favelas started to form in the 19th century, with Brazil’s transition from an empire to a republic. These spaces were first occupied by the urban poor, who had nowhere else to go and started to build. Skidmore explains in his book Brazil, Five Centuries of Change that citizens started to organize themselves internally. 1985 was a year marked by urban reforms, according to Bryan McCann in his book Hard Times in the Marvelous City. McCann also explains that in the following years, not only did the threat of large-scale removal end, and life conditions improved, but also a wave of police violence affected favelas in Rio de Janeiro.

With the arrival of the pandemic the scenario changed for the worse.

Monique Rodrigues, a single mother of two, lives in Morro dos Macacos in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro. She says that solidarity is crucial for survival during the pandemic. Assisted with the basic kit because she is now unemployed, she took part in a project called “Mãe e muito +” (in English “Mother and much more”), which works for social, economic, and emotional emancipation. Rodrigues is one of 400 women taking part.

Monique Rodrigues waits in line to get her basic kit in the NGO’s headquarters in Rio de Janeiro.

“I was lucky enough to be selected for a project that is not only focused on the now, but an investment in our future,” Rodrigues says.

Stellinha Moraes, a social entrepreneur who created the NGO “Anjos da Tia Stellinha” in 2014, also started “Mãe e muito +.” The NGO is focused on single mothers in Morro dos Macacos, and taking families out of extreme poverty, which is the reality of millions of Brazilians.

According to IBGE, there are 13.5 million Brazilians living in extreme poverty. People who live with under 145 Brazilian Reais per month, or around $27, are considered to be in extreme poverty. Moraes decided to help these families, who have as a monthly income from 90 to 150 Brazilian Reais, which is equivalent from 16 to 28 US dollars.

Families assisted by the NGO depend on a government program developed by former President Lula da Silva. “Bolsa Família” (in English: “family assistance”) was officially founded and named in 2003. The idea came from Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s government in 2001. In 2003, da Silva expanded two policies, the Bolsa Escola (school assistance) and Bolsa Alimentação (food assistance), bolstering Latin America’s most important social assistance programs.

Bolsa Família has decreased the number of people in extreme poverty and the levels of inequality. According to the World Bank, between 2003 and 2013, per capita income grew 56 percent in Brazil and poverty decreased from 12.7 percent to 4.9 percent.

With the coronavirus crisis, however, people who received this assistance and worked had their monthly income cut in half. This is Tamires Paulino’s reality in a favela in the north zone of Rio. She used to take care of the elderly and clean houses but has had no income since March. This made her even more dependent on the assistance provided by the federal government.

Since the pandemic started, Paulino’s life changed. A mother of five, she has been receiving the Bolsa Família since 2015. Because she qualifies as unemployed, she also qualifies for emergency aid provided by the government.

The Jair Bolsonaro government created the emergency aid for people who are unemployed or informal workers. The payments of 600 Brazilian Reais are about $113. According to Caixa Federal, a government owned bank, 63.5 million people have already received assistance.

“A lot of people are complaining about the emergency aid, saying that it is bureaucratic to get it, and that it takes a long time to get the money to pay me,” Paulino says. “I was lucky enough to have received it quickly and with no problem, since I’m also a Bolsa Família member.”

People like Paulino are now anxiously waiting for the time when she will be able to work again.

“People are very scared, but some are already back to work,” Paulino says. “I have been receiving calls from clients again, however, when I tell them the price I have always charged, they complain that they don’t have the money. I feel like employees are taking advantage of the fact that we desperately need the money to pay less for our work.”

According to IBGE, 41 percent of Brazil’s population works informally. When it comes to autonomous workers, there are 24 million out of a population of 209 million.

“Most of our mothers used to work in the third sector,” says Moraes “They used to work cleaning houses, selling sandwiches at the beach or cakes for birthday parties. With the pandemic, a lot of them lost their jobs or are not being hired.”

With the quarantine established in March in Rio de Janeiro, many single mothers stopped working and stopped earning money. The period of isolation has been a struggle for those who depended on the money earned on a weekly basis.

“Life was already hard for the mothers I work with. However, the pandemic made it all worse. In the beginning, we received a lot of donations, but in May, we started to worry about the lack of money we are receiving. People are not donating anymore,” Moraes says.

Moraes started to gather donations for other people at Morro dos Macacos outside of the work of her NGO, which already assists 70 families in the favela. An organization in Morro dos Macacos asked for her help to gather donations for other families also struggling because of the pandemic.

Once a week, people line up in long lines to get donations in front of the NGO’s headquarters in a two-floor beige house in the Grajaú neighborhood. Most recipients take their children with them to help carry donations or because they cannot leave them at home alone.

“What we realized is that our work is faster than the state’s. We have the power of articulation with the favela. We are able to reach all houses, the information navigates fast and donations arrive faster,” Moraes says.

“Ever since the pandemic started, there has been an increase in solidarity. Numbers of donations, however, are now decreasing,” says Mariana Serra, a social entrepreneur and founder of voluntourism agency Volunteer Vacations.

Serra says solidarity is sometimes a matter of survival and of living in community. People engage in causes because they see people struggling and feel it on their skin due to the proximity.

“One thing is a crisis somewhere far away, which is a reality that is not seen,” she says. “The other is a crisis everyone is suffering from and that can be seen right outside your door.”

She also explains that human beings are also impacted by their own “matter of survival” and this is the reason why donations have decreased.

Serra adds that this matter of survival can also reach a state level. An example for that was the competition for ventilators, which is when the U.S. ended up buying more ventilators than other countries because they had more money. This matter of survival can be crucial when it comes to choosing your own people or yourself.

She says that this wave of solidarity has an expiration date, which could be in December, “The biggest challenge is to maintain that wave of solidarity awakened by the coronavirus crisis. The numbers of donations are already decreasing, as several NGOs and graphics tell us.”

What Moraes and Serra have in common is that they usually do not work with emergency aid, such as the distribution of food and other basic resources. Both agree that emergency aid is needed in times of crises, like the pandemic.

“Right now, emergency aid is of extreme importance because it can save lives, and this is what people need right now: basic resources,” Serra says.

Serra’s company, Volunteer Vacations, which also partners with NGOs worldwide to promote volunteerism, focuses on structural aid.

“I was always interested in changing lives and comprehended that there was a marginalization of poverty, which harms the lives of thousands of mothers who get stuck in poverty,” Moraes says. “I wanted to help people change their lives, not focusing just on short term changes. However, emergency aid is also important to save lives, and this is why I have been using it in times of the coronavirus pandemic.”

Gaps Remain Despite Government Aid

In this context of economic desperation, hunger and poverty, Jair Bolsonaro’s administration established a policy to address extreme poverty for people who are not allowed to work because of the pandemic.

Some of the beneficiaries are artists who are not allowed to perform, waiters and waitresses who used to work at parties and people who used to sell candy on the streets near traffic lights in the luxury neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro.

“What is also helping us is the auxílio emergencial, the emergency support given by the government. This way, people can have a little bit of money. Some of them use this money not to live on the streets anymore and go to live in shelters,” says Juliana Telles, founder of an NGO that assists homeless people.

Telles created the NGO “A Nova Chance,” the New Chance, in 2016, when she joined a friend to distribute soup once a week in Copacabana, a neighborhood in the wealthiest zone of Rio de Janeiro, whose homeless population has been growing in recent years.

With the coronavirus pandemic, the number of people living on the streets also increased.

Telles used to distribute food once a week, however, with the arrival of the new coronavirus, activities needed to be intensified. Now, Telles produces around 100 to 120 meals to be delivered twice a week to homeless people in Copacabana. The project is secular, but they have support of a shelter financed by the evangelical church in “Del Castilho,” a neighborhood in northern Rio de Janeiro.

“So many people are unemployed right now. So many assisted people are now living depending on the ‘auxílio emergencial,’” Telles says. “There are fewer people transiting on the streets. What about people who worked on the streets selling candy and other items? What about the people who depended on that to live?”

As donations dry up, and government aid is debated, volunteers and organizers like Telles wonder what comes next.

Favela Residents Brace for Coronavirus Impacts

RIO DE JANEIRO- Two of the most important steps to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus are washing your hands and practicing social distancing. But for Brazil’s poorest, following those guidelines is nearly impossible.

“The mayor sent cars notifying us that we should wash our hands with soap, and stay at home for the next few days,” said Tamires Paulino, a resident of Morro dos Macacos. Paulino lives with her five children in Rio’s second biggest favela.

“But how does he expect us to wash our hands if we don’t even have water? Some of us receive soap donations, but you can’t really wash your hands only with soap,” she said.

The threat of the coronavirus to Brazil’s low-income communities has hit home in recent days. Rio de Janeiro’s first victim of the coronavirus was a 63-year-old housekeeper who worked in Leblon, one of the most exclusive neighborhoods in the country. The woman contracted the virus after her boss arrived from Italy and was waiting for her test results.

President Jair Bolsonaro compared the virus to a “small flu” on live television on March 24. In the same speech, he urged people to go back to work and said the mainstream media in Brazil was promoting hysteria. During the address, Brazilians banged pots and pans from their windows as a form of protest. In Brazil, the pandemic has already led to 77 deaths and 2,985 confirmed cases.

On March 22, the virus had reached at least four favelas in Rio de Janeiro. By March 26, Rio de Janeiro reported 421 cases and six deaths. The struggle to prevent the spread of the coronavirus has directed attention to places where the state is often absent. Residents of favelas are stepping in, educating their neighbors and addressing chronic problems, like water shortages, that will exacerbate the virus.

Residents of Complexo do Alemao hang warning signs with information about COVID-19. Picture credits: Photo courtesy of Bento/Coletivo Papo Reto.

“It took awhile for people in favelas to realize that the coronavirus was indeed an issue for them as well,” said Stella Moraes the founder of Anjos da Tia Stellinha, or Angels of Aunt Stellinha, an NGO that assists families that depend on federal welfare in Morro dos Macacos in northern Rio.

“Most mothers I work with kept telling me that this was a rich people’s disease since they are the ones who travel,” she said. “Well, now they know it affects everyone.”

Residents doubt that the government understands the full scope of the problem.

“I know at least ten suspected cases that haven’t been counted only in the community where I live,” Tatiana Viana, a resident of Morro dos Macacos, told LAND. “It is questionable if the released numbers correspond to the reality of Rio de Janeiro and Brazil.”

The situation is especially concerning because favelas usually lack open spaces. In the tightly packed neighborhoods, every square meter must be used. Most “barracos” or shacks have only a single room. It is common for several generations of a family to live together, since they do not earn enough to live in separate spaces.

This arrangement makes social distancing impossible for favela residents. Due to the lack of space between the so-called “casas de caminho,” twinned houses located in alleys, fresh air does not circulate. These are favorable circumstances for the virus to spread.

The most concerning infrastructure problem is the lack of water. Although some favelas have access to water that comes from the streets down the hill, crowded favelas face challenges to distribute water throughout the entire community. Most residents tap into the main water pipes coming into the neighborhood. But this means pumps are often compromised. When the overloaded water supply system stops working, it is to the detriment of the entire community.

An exposed water pipe located in the middle of the trash responsible for water supply in a house in Morro dos Macacos.

“These are the moments where we feel completely abandoned by the state,” said Viana. “I am self-employed and my money comes directly from the work I do each day. I have to go to the supermarket three times a week. It’s a huge privilege to go only once [to stock up]. Here we live day by day.”

LAND contacted CEDAE, the State Company responsible for water and sewer services, for comment on this story. The next day, CEDAE sent a team to one area of Morro dos Macacos to fix water pumps. Now, more members of the community have access to water despite the pump’s low pressure. Washing their hands will be a little easier.

A study by the Locomotiva Institute/Data Favela found that seven out of ten families that live in favelas throughout Brazil have had their income affected because of the crisis. Moreover, the same study also shows that 47 percent of favela residents are self-employed or informal workers.

Brazil’s Health Minister said on March 20th that COVID-19 is likely to cause a collapse in the health system. According to Dr. Guilherme Werneck, an epidemiologist at Rio de Janeiro’s State University, the number of beds in Rio de Janeiro is not enough to treat a pandemic.

“The biggest issue right now is the underfunding of the Sistema Único de Saúde,” or Unified Health System (SUS), said Dr. Werneck. The Brazilian universal healthcare system is one of the world’s largest, covering 210 million people, more than three fourths of the country. The recent passage of amendment 95 in 2019 limited public expenditures in areas such as health and education. The results are being seen and felt right now.

The state of Rio, with a population of 16.46 million people, has approximately 3.6 ICU beds available per 10,000 people. The problem, however, is that 70 percent of these hospital beds are not located in public hospitals, which is where 70 percent of the patients usually go.

Rio de Janeiro declared a state of financial emergency right before the Olympic Games in 2016. Four years later in March 2020, the state’s governor declared a state of emergency due to the coronavirus. Rio de Janeiro’s fragile finances and cuts to the public health system are the perfect recipe for the virus to take hold.

Rio’s Complexo do Alemão. Photo by Neila Marinho.

Werneck adds that the precarious conditions in the city’s favelas go strictly against the recommendations of the World Health Organization.

“What we see, on the other hand, is the mobilization of civil society in order to contain advances of the COVID-19 in more vulnerable areas throughout the country,” said Dr. Werneck.

Organized criminal groups and militias are trying to control the situation by imposing curfew in several favelas in Rio de Janeiro. According to messages delivered through social media and cars with loudspeakers, favela residents received death threats if seen on the streets after 8pm.The groups also oriented people to stay inside and only leave their houses in case of extreme emergency.

Other favelas residents are working to spread reliable information about the virus. Near Morro dos Macacos, communicators have been working hard to raise awareness. “Voz das Comunidades” started out in 2005, when 11-year-old Rene Silva decided to create a newspaper for the residents of “Morro do Adeus,” one of the favelas that form the “Complexo do Alemão” in Bonsucesso, in northern Rio. The publication became famous after Rene transmitted events of the military occupation in the Adeus slum in Rio live on Twitter in 2010.

Today, the communication platform works in nine different favelas in Rio de Janeiro to highlight social issues that residents face and to bring attention to people whose voices are not necessarily heard by mainstream media.

“Our main concern now is to do the best job we can, to alert and to give support to the ones who need it inside our communities,” Neila Marinho, a journalist and the organization’s press coordinator, told LAND.

“Voz das Comunidades” broadcasts live video streams on Instagram informing the population about daily news. As the pandemic spread, the organization started to dedicate time and space to educate people about its consequences. Their broadcasts became famous in the communities and reach thousands of viewers.

The next weeks will determine how the coronavirus impacts the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. The densely-populated neighborhoods lack the infrastructure necessary to prevent the spread of the virus. Public hospitals are likely to be overwhelmed. But civil society organizations and groups of neighbors are busy working to close the gap.

“We just hope that people follow our instructions,” said Marinho. “And that we make it out of this crisis quickly.”

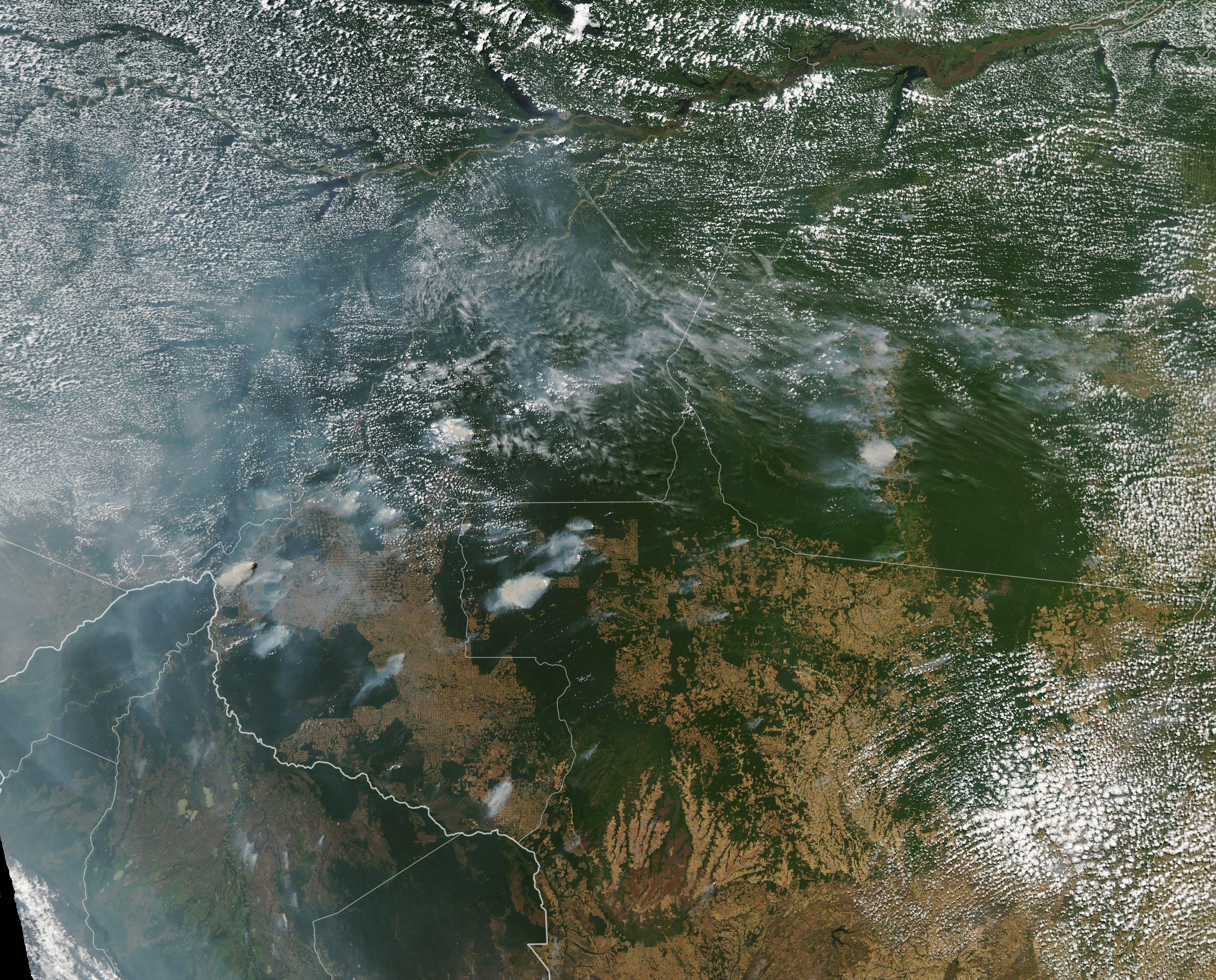

In Brazil, Growing Inequality Fuels Fires Burning the Amazon

NEW YORK — The fires in the Brazilian Amazon continue to burn more than two months after they first darkened the skies of São Paulo and caused an international outcry. As the rainforest speeds closer to its tipping point — when it will no longer be able to recover from deforestation — most of the outrage is focused on Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s environmental policies. But experts say the fires will continue, even if Bolsonaro changes these policies.

The country’s extreme social and economic inequality also contributes to deforestation. The number of fires in the rainforest tripled from 2018 to 2019, mirroring the growth of inequality in Brazil. According to a study conducted by FGV Social, a Brazilian higher education institution and think tank, inequality in the country has grown steadily since the end of 2014, with the income of the poorest half of the population declining 17% and the income of the richest 1% growing by 10%. The study cites higher cost of education and a rising unemployment rate as the main reasons for these numbers.

Gabriel Santos is a member of the Brazilian political movement Acredito, which aims to decrease inequality in the country and engage more Brazilians in politics. Santos, who came to New York City for last month’s Climate Week, running in conjunction with the United Nations General Assembly, said the sole focus on the environment in combating the Amazon fires is the wrong approach.

“Deforestation and preservation are also economic, social and political matters,” Santos said. “The singular focus on the environmental question, however, ignores all other factors that also contribute to deforestation.”

Data provided by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, shows that 40% of Brazilians older than 25 did not finish elementary school. Schools play an important role in teaching young Brazilians about conservation and sustainability, but they fail to do so when their students drop out. “How do you expect people who have never had access to education to be aware that they are indeed committing a serious crime, mostly in times of an economic crisis?” Santos said. “Of course, there are people who are consciously deforesting, but that is not always the case, and this is something we need to start talking about.”

Brazil is the world’s largest exporter of beef, and 80% of the rainforest’s deforestation is related to cattle ranching, according to the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. The land’s low cost and relatively easy transportation make cattle ranching a profitable and attractive business opportunity, together with soy cultivation in the Amazon, the study said. But the perceived economic benefits aren’t the only reason people are burning the rainforest, said Frederico Seifert, a finance manager at an environmental performance analysis company in Brazil called SITAWI.

“There is a predominantly false idea among some people in the region that burning up trees in the Amazon to make space for cattle and soy cultivation is an easy way out to make profit out of the forest, mostly poor Brazilians after the financial collapse,” Seifert said. He added that this idea undermines other reasons people set fires in the Amazon. “Socially, Brazil is still behind, and this is one of the main issues that affect all significant areas in the country. Environmental consciousness is missing. People need to be educated and be aware that we actually need the Amazon.”

The rhetoric of Bolsonaro and his administration hasn’t helped raise this consciousness. Before he assumed office, Bolsonaro chose Ernesto Araújo as Brazil’s next foreign minister, despite — or perhaps because of — Araújo’s claims that climate change is a Marxist plot, echoing some of Bolsonaro’s own beliefs. In August, Bolsonaro fired Ricardo Galvão, the director of Brazil’s National Space and Research Institute, known as INPE, after Galvão said deforestation was 88% higher in June 2019 than it was in the same month in 2018. In response, Bolsonaro called INPE’s findings “lies” and said two months later at his first UN General Assembly that the forest remains “untouched despite related NASA data which proves the increase of the fires.”

Some of Bolsonaro’s non-environmental policies are also contributing to the inequality growth, critics say, which may add fuel to the fires. Since his inauguration, Bolsonaro has been trying to transfer control of decisions on Indigenous land rights from Funai, a Brazilian agency that works for the protection of the Indigenous, to the Ministry of Agriculture, a move largely seen as reducing the power of the Indigenous and transferring it to large-scale farmers and other industries that want to develop the Amazon.

Franz Baumann, former United Nations special adviser on environment and peace operations, connected the Bolsonaro administration’s actions directly to the Amazon fires. “There have always been fires in Brazil — man-made, since natural ones are quite rare — but the uptick this year, induced by the new government, is concerning,” Baumann wrote in an email.

While opening up the Amazon for development could allow for short-term economic growth for some Brazilians, it doesn’t address the lack of education that lies at the heart of the country’s inequality. Seifert said addressing this issue is crucial in saving the Amazon. Banning deforestation alone isn’t enough.

“Environmental policies need to achieve more of an economic character,” Seifert said. “Otherwise this problem will never end. Brazil needs to stimulate the national economy so that it will grow, and people won’t feel the need to deforest anymore.”