Paramilitary Offensives Persist in Antioquia, Colombia

ITUANGO, Colombia– “When I was in the FARC-EP, I would see displaced people,” Wilmer said, drinking coffee in a cafeteria near an improvised refugee shelter.

“I would have to go to rural areas and the people would tell me that they had to leave their homes and I wouldn’t feel anything.”

Wilmer, 25, was one of 872 refugees who fled fighting between armed groups on February 23, near Ituango, Antioquia, in northern Colombia. LAND has changed his name for security reasons.

“When you experience displacement, you see how hard it is for yourself and everyone else,” he said.

A negotiated peace agreement in 2016 ended the 52-year armed conflict between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Colombian state. FARC militants agreed to reintegrate into civilian life. Wilmer is one of them. He reintegrated into a rural hamlet called El Cedral.

Ituango’s mayor provided the municipal gymnasium to shelter 325 people displaced from the rural sector of El Cedral, the largest of the 12 displaced communities. The other more sparsely populated communities were packed tightly in a small school just outside of town.

Three years after the FARC disarmed to the United Nations, the Colombian government is still unable to establish a presence in much of the remote countryside. Many regions that experienced relative calm under FARC hegemony are now a battleground between various armed groups struggling for control.

Caught in the middle of the war are former FARC combatants and social leaders. Since the signing of the peace accord, over 191 disarmed FARC and 323 social leaders have been assassinated nationwide. In Ituango alone, 12 former guerrillas and seven social leaders have been killed.

El Cedral community meeting after arriving to their improvised shelter (Pablo Cuellar/ VELA Collective)

Displaced communities seek refuge in Ituango

Wilmer is no stranger to hardship. His mother died of a sickness in Colombia’s neglected Pacific coast. His father was macheted to death. Wilmer ran away from a Medellín orphanage when he was 12. He walked over 100 miles to the coca fields bordering Ituango’s lowlands, one of the few places an underage child could get work. That’s where Wilmer met FARC guerrillas and asked to join them, when he was just 15. Even though he was a veteran foot soldier, Wilmer had never been forcefully displaced until now.

“We are here because of an order an armed group made yesterday morning telling us that we had to leave for our own safety,” said Jorge, a leader of El Cedral. LAND has changed his name for security reasons. “No one was allowed to stay. They said that they wouldn’t promise the safety of anyone who stayed.”

The order came from FARC dissidents who were expecting a paramilitary assault from neighboring Peque to the south. The armed group preemptively ordered the displacement to safeguard the community from their preferred method of war in this region, antipersonnel mines.

Most of the refugees were children and women. Many had little choice but to sleep on the cold concrete floors of the open-air gymnasium with just one blanket to share among an entire family.

Only eight of the refugees were ex-combatants of the FARC’s former 18th Front. Either they had family in the area or had married women in the local communities, like Wilmer.

The 18th Front controlled the region up until the peace deal, when 278 fighters disarmed in the UN-monitored Santa Lucia transitory zone in the mountain canyon neighboring El Cedral. Wilmer and several other ex-combatants moved to neighboring rural hamlets after handing over their weapons.

“No one slept the first night [after being displaced]. The dogs wouldn’t stop barking and crying,” said Jorge. “We aren’t used to sleeping like this, with all the noise. I’m used to sleeping in the mountains where the nights are quiet.”

“What most worries us are the animals we left behind. Mules, chickens, ducks, dogs, pigs,” said Yarcelly, Wilmer’s wife. “All we could do was leave as much feed on the ground as we had and let them loose to search for food themselves.”

Many of the poor farmers are already registered victims of the armed conflict due to a paramilitary offensive that burned their village in 2000. Their animals and land are the only form of capital they have.

Jorge, Wilmer, Yarcelly and hundreds of other farmers spent three nights away from their farms. Local authorities, typically slow to react, were able to provide food to the displaced. They returned home, but the risk of violence remains. In the month since the displacement, the army deactivated four mines in the area.

El Cedral rural hamlet (Nicolas Bedoya/ VELA Collective)

Paramilitaries flood “gateway” region

In January, the human rights ombudsman’s office in Colombia released an Early Warning System (SAT) report on Ituango. The reports alert other government institutions of “the likely occurrence of massive violations of human rights and international law.”

According to the report, armed groups have contested Ituango since the 1980s for being considered the “gateway” to the Nudo del Paramillo region.

The Nudo del Paramillo is a series of mountain valleys with dense jungle where the Andes mountain chain begins. An illegal drug and arms smuggling route runs through the region, circumventing government-controlled roads and connecting the Caribbean and Pacific Coasts with the coca producing region of Bajo Cauca.

The war in the region reached its peak in the 1990s and early 2000s, when several massive government and paramilitary offensives attempted to dislodge the FARC guerrillas from this strategic stronghold.

The now extinct Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC), United Self-Defense Groups of Colombia, paramilitaries committed the 1996 and 1997 massacres of El Aro and La Granja, which the Inter-American Human Rights Commission declared crimes against humanity. Paramilitaries also burned down El Cedral and Santa Lucia and displaced residents en masse in October 2000.

By 2006, the guerrillas had decisively defeated the AUC offensives but at a heavy human cost. Testimonies describe dump trucks filled with dead and rural roads lined with beheaded paramilitaries. The FARC kept control of the region until their demobilization in 2017.

“The paramilitaries always remembered what happened to them in Ituango. They see everyone here as guerrillas,” said Wilmer.

Armed group patrolling Nudo del Paramillo (Nicolas Bedoya/ VELA Collective).

Violence returns

After the FARC guerrillas withdrew from their territories and disarmed in 2017, many of Colombia’s rural regions were left with no authority. Ituango only had eight months of peace after the 2016 peace agreement before the killings started up again. The strategic region of Ituango is once again being contested in a bloody war between paramilitaries, security forces, and FARC dissidents.

According to the SAT report, the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC), or Gaitan Colombian Self-Defense Group, paramilitary emerged from the failed AUC demobilization in 2006. They have been slowly consolidating a path that cuts through the Nudo del Paramillo with the goal of linking up their territories in Bajo Cauca to the west and Peque to the south. After 30 years, the paramilitaries have finally been able to gain a foothold in their former enemy’s territory.

Many leaders believe the blood spilling is only going to get worse. Guerrillas disillusioned with the faltering peace process formed the “New FARC 18th Front Cacique Coyara” at the end of 2017. Several experienced former guerrillas and have quickly grown the group’s ranks by recruiting youth in their total war against the AGC.

Communiques from the dissidents have stated their intention of a “paramilitary cleansing.”

“There is a lot of fear and no security. There are no guarantees for civilians and much less for us ex-combatants,” said Wilmer. “If anything, the army sends troops to our canyon and they stay twenty days, a month at most. After that, armed groups can do what they want with the communities.”

So far, the army and police have been unable to effectively combat these groups and outpace their ability to recruit. Security forces themselves have been accused of serious human rights abuses and extrajudicial killings known as “false positives.”

This is the practice of the army killing civilians and presenting them as guerrillas killed in combat. The peak of the practice took place during the administration of former President Alvaro Uribe Velez in the mid-2000s but continues today.

Dissidents train new recruits in live fire. (Nicolas Bedoya/ VELA Collective)

Local conflicts persist

Ituango’s mayor, Mauricio Mira, embodies the open wounds left by Colombia’s civil war. Mira was blocked from running for mayor in 2015 by the FARC guerrillas.

“The guerrillas kidnapped me for three days, I’ve received several death threats, and was then displaced in 2015,” Mira told LAND.

But he has also disparaged communities like El Cedral. As a candidate in October 2019, Mauricio Mira said in an interview with LAND that the people in El Cedral are “lazy” and that, “Every time there is a displacement, they are the first to be ready to go to see what they can get.”

He won the 2019 mayoral election by just 100 votes.

Displaced prepare to return to their communities after four days (Pablo Cuellar/ VELA Collective)

Mira’s first major emergency as mayor would be the mass displacement of the community he stigmatized. The government and mayor’s office provided food and hygiene kits and supported the voluntary return of the communities.

“In Ituango, the army should have occupied the land that was left by the FARC after the peace process,” said Mira. “While the territory has coca crops for cocaine production, we will never get rid of the armed groups.”

The inhabitants of El Cedral, who themselves don’t grow coca but live in the strategic canyon between coca fields and the rest of the country, expect to be displaced again in a few months as the violence picks up.

The murder of an boy on March 22 and a dissident commander five days later in one of the displaced communities is a reminder that the conflict won’t stop, even with the onset of coronavirus.

At least Ituango has a head start mitigating the spread of the new virus. Since last year, armed groups have enforced a 6pm curfew.

While the people of El Cedral returned home, the risk of violence in Ituango remains.

Mayor of Ituango (far left with glasses) listens to Augustin, the former FARC 18th front commander, speak. (Nicolas Bedoya/ VELA Collective)

180th Ex-FARC Guerrilla Member Is Killed in Colombia, Increasing Pressure on Peace Process

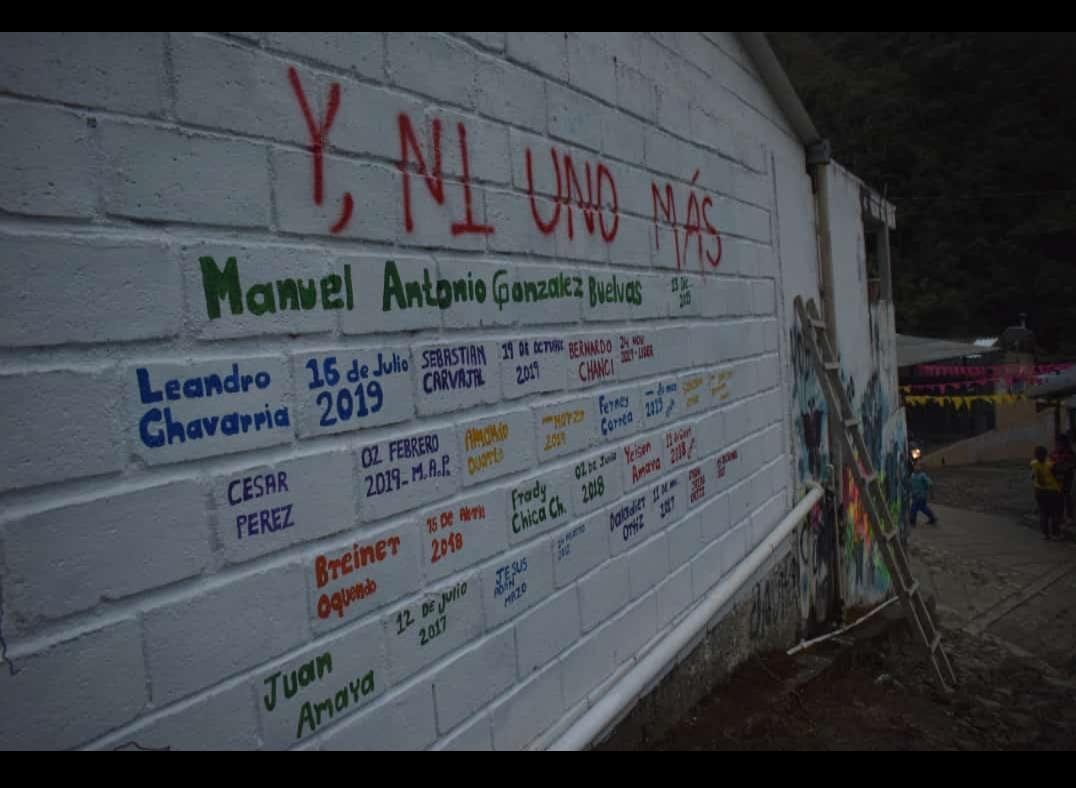

On Tuesday, the rural community of Santa Lucía in northern Colombia held a ceremony to grieve the death of another ex-combatant. Manuel Gonzalez was the 180th FARC guerrilla member to be killed in Colombia since the signing of a peace accord in 2016 between the rebel group and the government.

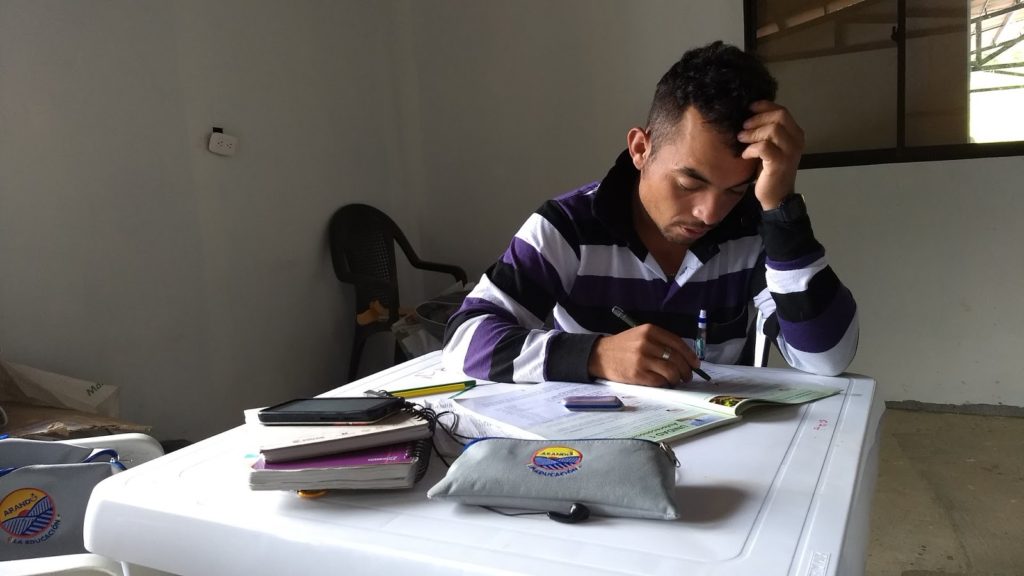

Gonzalez joined the FARC guerrillas when he was 15 years old. The peace deal gave him a shot at a “normal” civilian life after 14 years fighting the government deep in the jungle. He settled down in Santa Lucía where he was undergoing the reintegration process. The small rural hamlet hosts a territorial training and reintegration camp for over 70 former guerrilla fighters of the FARC. They are part of the 7,000 ex-combatants who demobilized and turned over their weapons to the United Nations.

At the camp, Gonzalez learned to read and write, taking advantage of educational opportunities denied to him during years of armed conflict. In February, Gonzalez’s wife gave birth to a baby girl. He supported his family working in a collective cattle project and as a motorcycle taxi driver.

Manuel Gonzalez learned to read and write in the Santa Lucía reintegration camp. (Photo by Viviana Vargas)

Last Friday around 1 p.m., Gonzalez got a request to take a passenger to the small town of Ituango — an hour and a half away on his motorcycle. On the journey back, he was stopped by armed men just 40 minutes from the camp. Gonzalez was forced to lay face down on the ground, and he was executed. Following his death, the FARC released a statement condemning the warning left by the armed group: “any ex-combatant seen transiting the road today will be killed.”

Franklin, a friend of Gonzalez’s and fellow ex-combatant living in Santa Lucía who goes by an alias, said he found out about Gonzalez’s death about three hours after it happened.

“Here you can’t move at night,” Franklin said over the phone. Armed groups had imposed a curfew preventing any movement on rural roads past sunset. “It was hard because authorities wouldn’t retrieve the body.”

Despite the fear and danger of violating the curfew, the community refused to leave Gonzalez’s body on the road. “Out of the pain and impotence we all felt, 14 of us decided to go pick him up and bring him to the camp,” Franklin said.

The community waited until the next morning for authorities and crime scene investigators to arrive at the camp and take the body. However, faith in government security forces hangs by a thread in this region. Ituango, the municipality where Santa Lucía is located, boasted one of the highest homicide rates in Colombia in 2018, and 11 ex-combatants have been killed there since the signing of the peace accord.

Thirty years after armed groups began operating in Ituango, the area once again became a conflict zone at the end of 2017. The government proved ineffective in preventing narco paramilitary groups from taking over former FARC territories. Paramilitary offensives in former rebel territory have led to a rise in the number of guerrillas choosing to rearm to combat their old nemesis.

“Ituango has taken the worst of this peace process by far,” commented one woman who was forced to leave her hometown last year. She didn’t want to provide her name for safety reasons. In November alone, fighting between FARC dissidents and the Clan del Golfo paramilitary group displaced over 200 people in the municipality.

However, it is not only ex-combatants who have been targeted. In the last three years, over 700 social leaders have been killed too. Bernardo Chancí, a community leader who promoted the government’s voluntary substitution of coca crops, was assassinated in Ituango just 20 days before Gonzalez was killed. The police also “accidently” shot social leader Ferney Piedrahita outside his home last month without warning, allegedly mistaking him for a combatant.

“The implementation of the peace process requires very delicate leadership,” Franklin said. “Any loss of an ex-combatant or social leader is an attack on the peace process. Unfortunately, us Colombians have gotten used to getting killed. We pick up the dead and bury them, we pick them up and bury them again. Nothing changes.”

Many fear the new FARC political party, whose leaders are mostly ex-combatants, will share the fate of the Patriotic Union political party, which was born out of peace negotiations in 1985. Throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, over 2,000 of its members and politicians were systematically assassinated by security forces and paramilitaries. Many ex-combatants say this is already becoming true of the FARC. Elmer Arrieta, Gonzalez’s father, has received multiple death threats. Arrieta recently ran for the departmental assembly as a candidate for the FARC political party. Before the peace process, he was the second in command of the FARC front that operated in Ituango.

“Today they took my son, but not just from me,” Arrieta said at his son’s burial on Tuesday. “They took him from the people, from peace and from the hope that reconciliation will prevail. Peace should not cost us our lives.”

At the end of the ceremony, the Santa Lucía community painted a mural listing the names of their dead loved ones at the entrance of the hamlet. With the situation growing more tense by the day, the sobering list is only expected to get longer.

As Violence Continues at Home, Exiled Colombians Reconstruct Collective Memory

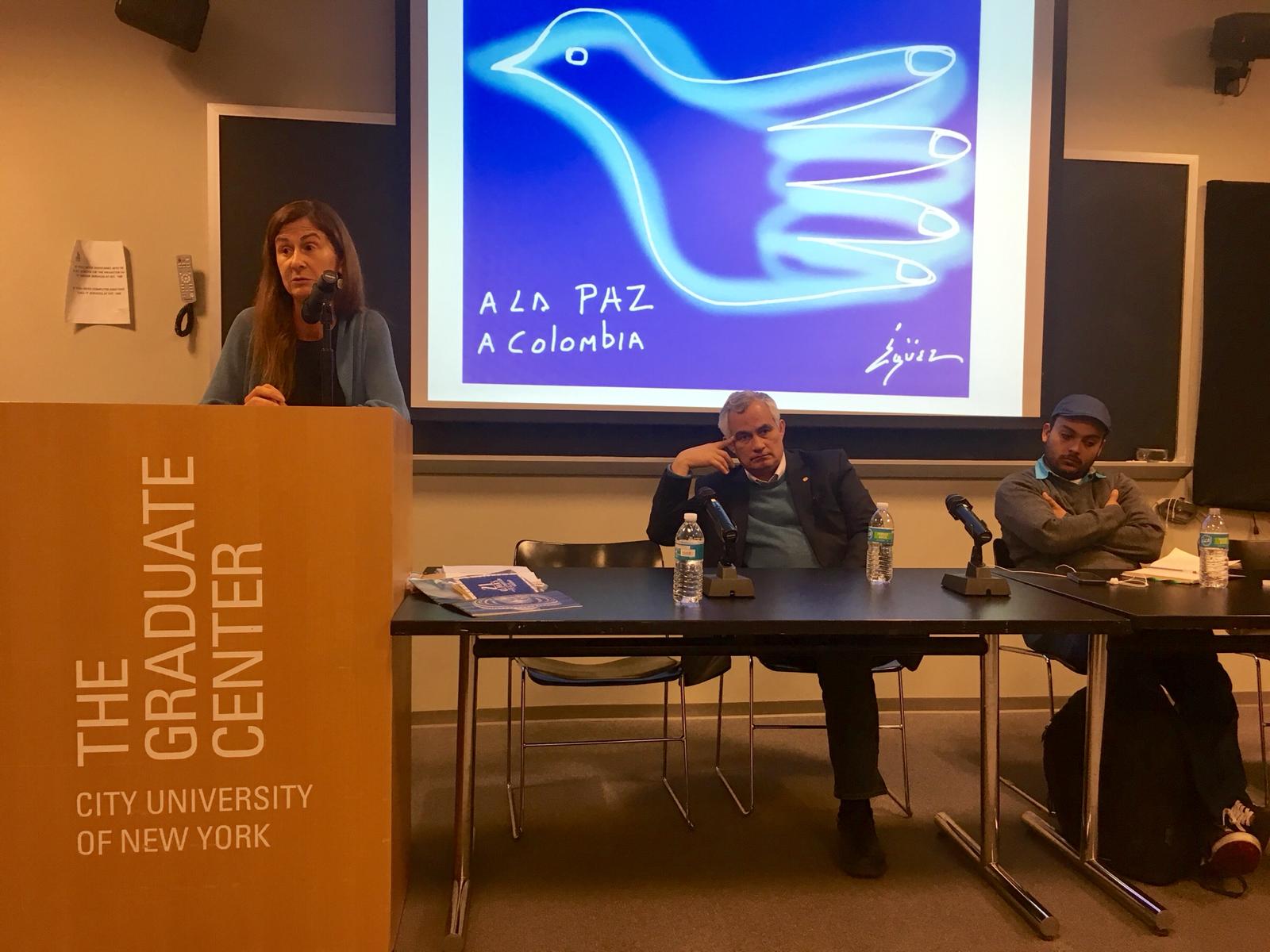

In a small classroom at the City University of New York (CUNY), exiled Colombians gathered to talk with Arancha García del Soto on April 16. Del Soto is part of Colombia’s Commission for Truth Clarification, Peaceful Coexistence and Non-Repetition, also known as the Truth Commission, tasked with piecing together the complex history of the country’s decades-long armed conflict.

Although there is no reliable statistic, del Soto says there are an estimated 350,000 to 500,000 exiled Colombians as a result of the internal armed conflict, which, despite a peace agreement signed in December 2016, continues to rage. Since the signing of the peace deal, over 450 social leaders have been murdered.

As a result of the historic peace accord with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the Colombian government created the Truth Commission to gather the collective and individual memories of the victims of the conflict. It’s the first commission of its kind in the country’s history. The event in New York offered the exile community the chance to contribute their own memories, which have historically been silenced, according to Mary Roldán, a professor of Latin American history at CUNY who has researched the conflict in Colombia.

“The incapacity of people to share their voice and see their story reflected in the official narrative that gets published and reproduced in a country is a way to suppress the lives of others but also marginalize and exclude,” Roldán said.

At the end of it’s three-year mandate, the Truth Commission must produce a final report that explains what happened during the armed conflict, why it happened, the consequences of the violence and recommendations for ending the cycles of violence.

The commission is led by the Jesuit priest Francisco de Roux, who is well-known for his defense of human rights and work in some of the most hostile places in Colombia. De Roux has witnessed the worst of Colombia’s armed conflict, having buried 27 of his murdered friends and coworkers. Only one member of the commission, Carlos Martín Beristain, was born outside of Colombia. It was Beristain who proposed working with the exile community. He and a team of 40 specialists, including del Soto, are traveling the globe and defining the methodology for the task. After the inauguration of the Truth Commission in November, del Soto and Beristain got straight to work in their native Spain and then traveled to Germany, France, Switzerland, Australia and now the United States to meet with the dispersed exile population. This community often has been overlooked due to the impression in Colombia that they were better off and had more opportunities, but exiled Colombians see it differently.

“In Colombia, leaders are killed, but here in the United States, even though we have freedom of expression, we are killed morally,” Yolanda Naranjo said at the CUNY event.

Francisco de Roux leads a moment of silence before starting a meeting with exiled Colombians in Washington, D.C., in November 2018. (Photo by Nico Bedoya)

The pain of leaving their homes and families and uprooting their lives with no or little support has further silenced victims. The Truth Commission hopes its presence in countries with exiled Colombian populations will cultivate the trust necessary for victims to share their painful stories. However, the new Colombian government, headed by President Iván Duque and the Democratic Center governing party, has been openly hostile to the commission. By the time the commission was inaugurated on Nov. 28, 2018, their budget had been reduced by 40%. “This is an attempt to strangle the commission,” del Soto said.

As a presidential candidate, Duque wrote an op-ed in El Colombiano, a national newspaper, hinting that he believed the commission was trying to justify the armed rebellion of the FARC. To dispel these accusations, del Soto reiterated several times during the meeting that the commission wants the testimonies of all victims willing to tell their stories, no matter their politics or affiliations with armed groups. Since the Truth Commission is an extrajudicial body, the victims’ testimonies can have no legal repercussions, providing more incentive for victims and victimizers to tell the truth.

“Transitional justice is black and white, but the historical truth is gray,” de Roux said at a meeting with exiled victims in Washington, D.C., in November.

At the meetings held in the United States, exiled journalists, politicians, businessmen and religious and social leaders have answered the commission’s call. Victims of paramilitaries, the national army and guerrillas have attended these initial meetings to hear the mission and methodology of the commission. In many cases, the pain of exile has passed on to the next generation. In Washington, the children of victims attended the meeting instead of their parents, who said they preferred to not reopen wounds.

Del Soto and Beristain have opted for a psychosocial approach to the victims, prioritizing their well-being to avoid re-victimizing them. “Our biggest challenge is in creating that trust and the collective environment necessary to share that pain that is so fragmented, divided and hidden,” del Soto said.

In today’s world where “truths” themselves have become the subject of debates, the work of the commission may seem impossible. But for the dozens of victims and commissioners who meet behind the closed doors of universities, the truth of the conflict is slowly being pieced together.

“Silence kills but you can’t cover up the truth,” del Soto said. “The same way you can exhume bodies, you can also exhume the truth. That is our conviction.”