As Protests Against Local Government Flare Up Across Paraguay, a 17-Year-Old Student Leads the Charge in One Town

ASUNCIÓN, Paraguay—In recent weeks, the town of Mayor Otaño in southeastern Paraguay has been the scene of a dramatic protest over alleged misuse of public funds by local authorities. And high school students, with 17-year-old activist Nelson Maciel at the helm, have been leading this protest — just one in a series of local movements against perceived corruption erupting in Paraguayan towns and cities.

Maciel, already a seasoned campaigner with numerous national and international youth organizations, said that he and other members of the student union at Mayor Otaño’s public school became deeply concerned about the town hall’s finances after hearing municipal councilors mention irregular spending practices on a local radio show in August.

“Hearing that woke us up,” Maciel said at a restaurant in central Asunción, the capital of Paraguay, shortly after a meeting with the attorney general to discuss events in his hometown. “We decided to ask those same councilors for documents from the town hall so that we could take action regarding the situation. They gave us enormous amounts of papers. It took us around a month to study them and draw our conclusions.”

He said that their analysis uncovered what they believe is proof of massive inconsistencies in public spending. For example, they claim that large contracts for road maintenance were given to a business owned by Mayor Pedro Chávez’s brother, who went on to invoice the municipality for nonexistent costs.

Another large point of suspicion was apparent misuse of funds from the National Fund for Public Investment and Development (FONACIDE). FONACIDE is a large public pot originating from the sale of electricity from the Itaipú Dam to Brazil. Municipal governments receive a portion of this money and are required to spend 80% of it on projects related to education.

“The money reserved for education was used to build a bridge — a bridge leading to the mayor’s farm,” Maciel said. “The rules of FONACIDE say that all infrastructure projects must be within two kilometers of a public school. In this case, the nearest school was 10.5 kilometers away.”

In September, they decided to act on their discoveries, positioning the misuse of FONACIDE money as the central point of their campaign. They began protesting outside Mayor Otaño’s town hall, demanding that authorities make their spending accounts publicly available. They also called for the mayor’s resignation and asked the town council to request an audit from the National Comptroller General’s Office. These demands have not yet been met.

Criminalizing Young Activists

Since taking action, the students have faced a strong reaction from Chávez and his allies. Tension between critics and supporters of the mayor has manifested in an eruption of physical violence. Maciel himself suffered a head injury during a scuffle involving a police officer outside the town hall.

The young activist also said that he has received death threats and must now rely on private vehicles and drivers to guarantee his safety. His mother was told by the president of the local association of the Colorado Party — Chávez’s political party — that she would lose her job as a cleaner at the Mayor Otaño’s public health center if she did not intervene in her son’s activism. Maciel has not slowed down, and she was subsequently fired. The Ministry of Health offered her a new position only after an intervention from Paraguayan president Mario Abdo Benítez.

In addition, Chávez and other local figures from the Colorado Party, have brought a total of four libel actions against Maciel for his role as leader of the protest.

Student protesters bear the Paraguayan flag in a protest against the suspected corruption in the office of Mayor Pedro Chávez. (Photo by Diego Pusineri)

Walter Isasi, lawyer for the Paraguayan Human Rights Coordination Group (CODEHUPY), said, “These legal suits are really just a form of intimidation being used to block Nelson’s right to demand transparency. Free access to public information is a universal human right.”

Isasi claimed that the tactic of criminalizing activists has been used in other cases against young people who have taken a stand against authority in Paraguay. In August, a long battle saw student activist Ernesto Ojeda absolved of charges brought against him for participating in a protest that pushed for improvements in the education system in the city of Fernando de la Mora in 2017. He said the government has not moved to defend Maciel from the danger surrounding him.

“I don’t have knowledge of actions taken by the state in response to the violence that Nelson has experienced,” Isasi said. “Only the Ministry for Childhood and Adolescence has taken a stand.”

The Ministry for Childhood and Adolescence published a press release in the aftermath of the protest in which Maciel received a head injury. The state institution denounced the use of “intimidation” to block the youth leader’s expression of his rights.

Despite this adversity, protesters have pushed on. The National Comptroller General’s Office did carry out an audit — without the approval of the town council, according to Maciel — and found that there had been a possible misuse of 1 billion guaranies (USD 154,466) of public funds. The report, which was submitted to the public prosecutor’s office, includes a list of 15 serious signs of embezzlement within the municipality. Mayor Chávez denies wrongdoing.

Beyond Corruption

The protest in Mayor Otaño is by no means unique. Other towns and cities across Paraguay have been witnessing upheavals in response to perceived wrongdoing by local authorities.

Citizens egged the mayor of Arroyito and complained about “ghost projects” — initiatives that were paid for but that only appear on paper. In early November, councilors in the city of Lambaré requested an intervention in the administration of Mayor Armando Gómez due to multiple financial irregularities that left the municipality with no funds to pay its employees.

The Paraguayan news media also frequently publish articles on municipalities’ mass failings to properly administer funds. For example, it was reported this year that over 97% of municipalities did not acceptably justify their FONACIDE spending.

The town hall of Mayor Otaño following one of a series of protests led by student activists. (Photo by Diego Pusineri)

Mariela Centurión, director of the independent Center for Investigation and Studies of Public Administration and Governability (CIAG), said these figures should not lead people to jump to generalized conclusions about the honesty of Paraguay’s municipal administrators. She said that while corruption is undoubtedly a large and important factor that must be addressed in places like Mayor Otaño, other elements are at play in hindering the effective administration of municipal budgets.

“The message that these articles put across, which I think is extremely severe, is that municipalities are incapable of managing their own resources and fulfilling their functions,” she said.

Centurión points to figures from FONACIDE that, if accurate, indicate that the misuse of funds is nowhere near as endemic as is often implied. Over the period of 2013 to June 2019, municipal governments received USD $365.5 million from FONACIDE. Of this total, just 0.69% was employed illegally, according to FONACIDE. Centurión said that the worrying figures reported in the press can be attributed to other factors besides corruption, such as widespread administrative errors.

Paraguayan municipalities have largely been victims of a poorly executed plan to decentralize power that began with the new constitution of 1992, Centurión added.

“There’s a contradiction. On the one hand, the constitution mentions a mandate of decentralization, but there are no laws, no regulations nor resources to drive the process of strengthening municipal governments,” she said. “There is no training for municipal employees. Work from the executive branch to fulfill its responsibility of working with municipal staff to modernize municipal management is entirely absent.”

This lack of support leads to poor performance in local governments, including the frequently botched reporting of spending. The executive branch, she said, has set municipal governments up as its scapegoat.

Centurión expressed worry that the portrayal of municipal governments as innately corrupt institutions threatens their ability to work with local communities. She said that municipalities are unrivaled in their capacity to identify the needs of residents: if their responsibilities are taken away from them as a result of this perception of ineptitude, this great benefit will be lost.

The very low participation of citizens in the day-to-day running and decision-making processes of local government is another concerning factor, according to Centurión. She claimed that beyond participating in elections, there is limited interest in using the mechanisms available to allow locals to form part of the workings of their institutions and regulate public spending to deter corruption.

“I think that in Paraguay, we haven’t been able to develop the ability to hold a dialogue and debate,” she said.

Centurión said that this lack of regular involvement can lead to lowered trust in institutions and, in cases where corruption is present, a vital filter is lost. This disconnect can lead to a buildup of tension, with consequent explosive reactions from citizens. She said that the multiple protests of recent weeks should be a wake-up call to the Paraguayan government: citizen participation must be encouraged at all levels of local government in order to empower residents to regulate and shape municipalities’ activities and spending.

According to Nelson Maciel, the low participation of the population of Mayor Otaño in vetting the running of its town hall has allowed for all types of wrongdoing over the years. The current protests, he said, are the first step in changing this.

“Mayor Otaño is a submissive town in which people don’t challenge the status quo,” Maciel said. “There has never been a citizen protest in response to the actions of a politician. People have been put to sleep by so much fear and injustice. Now, we, the young people, are working with the community. It’s only a question of igniting the flame so that they can go out onto the streets to demand what is theirs.”

With the Help of Nuns and a Lawyer, a Paraguayan Indigenous Group Wins Back Their Ancestral Territory

ASUNCIÓN, Paraguay—In early May, the Jejyty Miri Indigenous community in Paraguay received the good news they’d been waiting for. After three years of struggle over their 500-hectare territory near the town of Itakyry in the department of Alto Paraná, they won the right to return to the land they claim is their ancestral territory.

“After going through so many difficulties, hearing this decision makes us very happy,” Marciana Araujo, a member of the community, said. “It’s incredibly important. It means we have the possibility of going back.”

The Jejyty Miri community’s struggle for land is by no means unique among Paraguay’s roughly 500 Indigenous communities. A 2015 report from the United Nations special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples states that in addition to the 134 Indigenous communities that are entirely landless, 145 communities face problems related to the possession of their territories, such as ownership conflicts with business enterprises. Few of these communities manage to win their battles in the courtroom as the Jejyty Miri has done, however.

The Jejyty Miri community, who are part of the Ava Guaraní Indigenous people in eastern Paraguay, won their case with the help of an organization run by nuns. The Espíritu Santo Pastoral Mission has won land rights cases for about 30 Indigenous communities involving more than 25,000 hectares of land, according to Sister Mariblanca Barón, a founding member of the organization.

“We have an efficient lawyer, and we, the nuns, are good at what we do, too,” Barón said. “Those communities have the deeds in their hands.”

Members of the Jejyty Miri community with the Espíritu Santo Team. Front row left to right: Maricana Araujo, Sister Mariblanca Barón, Sabino Piris, Aníbal Alfonso. (Photo by William Costa)

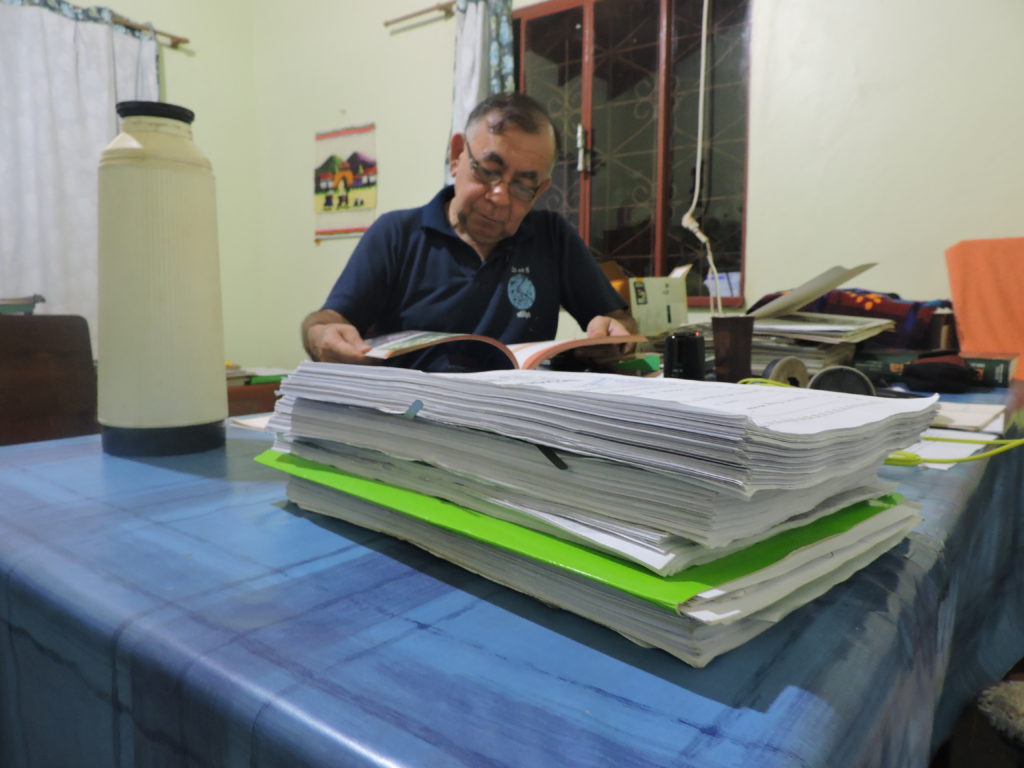

For more than 40 years, the nuns at the mission have collected records and legal documents related to the Ava Guaraní people, helping them win land rights cases and amassing an enormous archive of evidence of their legal land rights. Aníbal Alfonso, the mission’s lawyer who represented the Jejyty Miri, used this archive to piece together a five-tome, 500-page dossier to defend Jejyty Miri’s claims over its land.

“This is the center of it all. This is our laboratory,” Alfonso said of the archive, located in the small town of Nueva Esperanza. “Here, we study the documents and see what we have to work with. In the case of Jejyty Miri, we have very strong proofs. There’s a lot of documentation.”

The dossier Alfonso created includes photos, letters from public ministries and contracts. To the soy farmers fighting against Jejyty Miri, the 500 hectares of disputed land represent money — specifically $6 million. But to the Jejyty Miri, the land has more than economic value.

“For the community, alongside what it represents economically, it also has an affective, emotional value,” Alfonso said. “It is the source of their way of life, of their culture. If they are stripped of their land, of their territory, as so many other communities have been, they also lose their customs, their traditions.”

Aníbal Alfonso goes over the case dossier. (Photo by William Costa)

For the Jejyty Miri, the trouble began in 2016 when a conflict with a Brazilian soy farmer erupted over ownership of the lands traditionally inhabited by the community. The Indigenous group suffered repeated instances of threats and intimidation, which culminated in a violent eviction from the territory in early December 2017.

“They burnt our homes, and they almost burnt my children who were inside,” Araujo said.

Gunmen fired on the Jejyty Miri, hitting Araujo’s husband, Sabino Piris, who is a leader in the community. The assailants then burned their homes and used bulldozers to destroy their crops. The Indigenous families initially resisted but were soon overwhelmed.

One of the main causes of Indigenous land rights conflicts in Paraguay is the sustained boom in soy farming, which started in the 1960s, according to Luis Rojas, an economist researching rural development in Paraguay. The purchase of enormous swathes of land — using both legal and illegal means — by select, wealthy groups has dramatically increased the area employed for intensive soy cultivation from 1,200,000 hectares in 2000 to almost 3,600,000 at present. This trend has largely contributed to Paraguay’s status as the most unequal country in the world in relation to land ownership, according to the World Bank.

Soy fields near the Jejyty Miri land. (Photo by William Costa)

“This skewed distribution of Paraguay’s land is a source of permanent conflict, a conflict that wages between the powerful mechanized agriculture sector on the one hand and the Indigenous and peasant farmer sectors on the other,” Rojas said.

The virgin lands of eastern Paraguay have now been almost entirely incorporated into the soy and cattle-ranching sectors, with only about 10% of the once vast Atlantic Forest of the region left. As a result, industrial farmers have largely turned their attention to areas held by other groups, such as Indigenous peoples, in order to further the expansion of the green sea of soy.

Farmers have frequently taken over Indigenous land by claiming they have deeds to the land. This is what happened to the 500-hectare territory of the Jejyty Miri, the lawyer Alfonso said. After the Jejyty Miri were evicted from their homes, they were forced onto a 15-hectare section of the territory. The soy farmer defended himself by saying the Indigenous community always lived on the 15-hectare section, but not on the rest of the territory.

“Indigenous communities are vulnerable,” Alfonso said. “They don’t have many ways of defending themselves. The soy farmers know that.”

The soy farmer who took over the Jejyty Miri land exploited a bad land deal made by the state in 1996. The government bought the 500 hectares for the Indigenous group, but they purchased it from someone who did not have the authority to sell it, according to Óscar Ayala, executive secretary of the Paraguayan Human Rights Coordination Group (CODEHUPY). The deal came back to haunt the community years later as they fought to stay on the land.

“Once again, we are seeing a case where corruption has produced conditions in which the rights of an Indigenous community have been violated,” Ayala said in an interview with the La Unión radio station.

The Paraguayan Constitution establishes the right of Indigenous peoples to communal ownership of their lands and prohibits their removal from these areas without their direct consent. Additionally, Paraguay is party to several international treaties that act to protect Indigenous land rights. The state’s refusal to guarantee the territory of Jejyty Miri was a grave violation of the legal guarantees held by Paraguay’s Indigenous population. The state’s actions are hardly surprising, however. Historically, authorities in Paraguay have strongly favored the interests of powerful landholders over Indigenous communities.

“From a legal perspective, the state has all the necessary conditions to fully recover ownership of the land and to finalize the deeds for this Indigenous community,” Ayala said.

The state still did not act, however, forcing the Jejyty Miri to embark on a three-year legal battle, with Alfonso and the nuns at their side. In the end, after a successful appeal by Alfonso, the court declared that the land was the rightful possession of the Jejyty Miri community.

“We’ve won the case. We’ve categorically won,” Alfonso said. “They’ve awarded us 100% of what we were asking for.”

Following the announcement of the legal decision, members of the Espíritu Santo Pastoral Mission traveled to the 15-hectare area, where the community is living, to share the news. After a ceremony on June 19, the Indigenous families will return to their ancestral 500-hectare home. For community members like Araujo, the homecoming is not just a victory for them, but also for their ancestors.

“Our grandfathers and grandmothers are in the cemetery,” Araujo said. “We couldn’t leave them behind.”