Andes, Colombia, Photo Essays

Outrage Over Rising Violence in Colombia Explodes Across Borders

August 7, 2019 By Hanna Wallis

NEW YORK — The desperate screams of a small child witnessing his mother’s murder in Colombia echoed around the world on July 26, when people in 80 cities around the world protested the country’s ongoing epidemic of social leader assassinations. A viral video in late June caught one of these killings on tape for the first time, showing Maria del Pilar Hurtado’s lifeless body lying on the floor in front of her young, traumatized son. Since then, Colombians’ outrage at the unrelenting wave of murders has exploded on an international scale, galvanizing the Grito por La Vida — Cry for Life — mobilization.

In New York, hundreds of people gathered in Washington Square Park as 10,000 others flooded into Bogotá’s Plaza Bolívar. In both hemispheres, the same chants rang out: “stop the violence!” “not one more!” and “they are killing us.”

An activist in New York reads an impassioned pronouncement about the urgency to stop social leader assassinations. Behind him, people hold the Colombian flag. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

A crowd watches the speeches at dusk. Two women hold signs that read “It doesn’t cost a life to care for it,” and “No one should have to die for defending the rights of all of us.” (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

During the past three years, more than 700 social leaders have been slain in Colombia, according to the Bogotá-based Institute for Peace and Development Studies (INDEPAZ) — an average of one murder every three days. The demonstration on July 26 is part of a growing movement to challenge violence in Colombia, and it reflects deep and far-reaching outrage with the government of President Iván Duque, which has done little to intervene.

In March, Colombians unified on a historic scale to shut down the Pan-American Highway for 27 days, demanding that Duque address their urgent pleas for peace and justice. Four months later, with no foreseeable end to the conditions that have fueled the violence, the Grito por la Vida symbolizes an afterlife and expansion of that struggle.

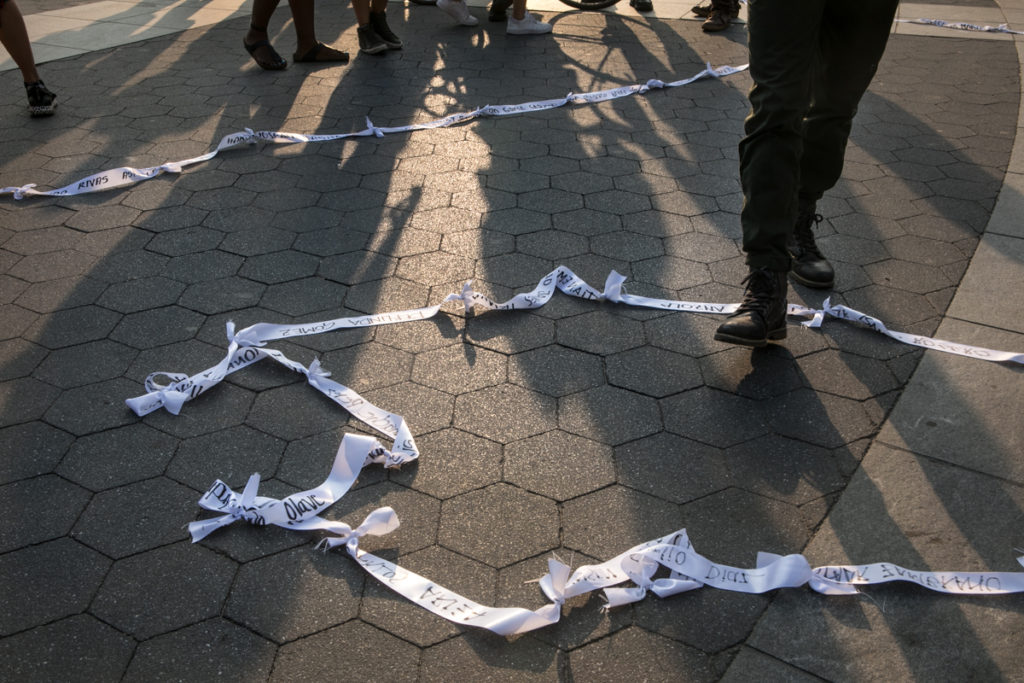

The majority of assailants responsible for social leader killings are never prosecuted or identified. Meanwhile, images of the dead fill streets around the world. Protesters in New York unfurled a long strip of white cloth, each foot-long piece of the chain bearing the name of a murdered leader in black ink. They circled the park’s central fountain multiple times, but not enough demonstrators were present to fully unspool the ribbon of victims from its tangled heap on the pavement.

Protesters wrap a chain of white cloth around the fountain at Washington Square Park as one of them carries a Colombian flag. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

The names of victims are splayed all over the ground on pieces of white fabric. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

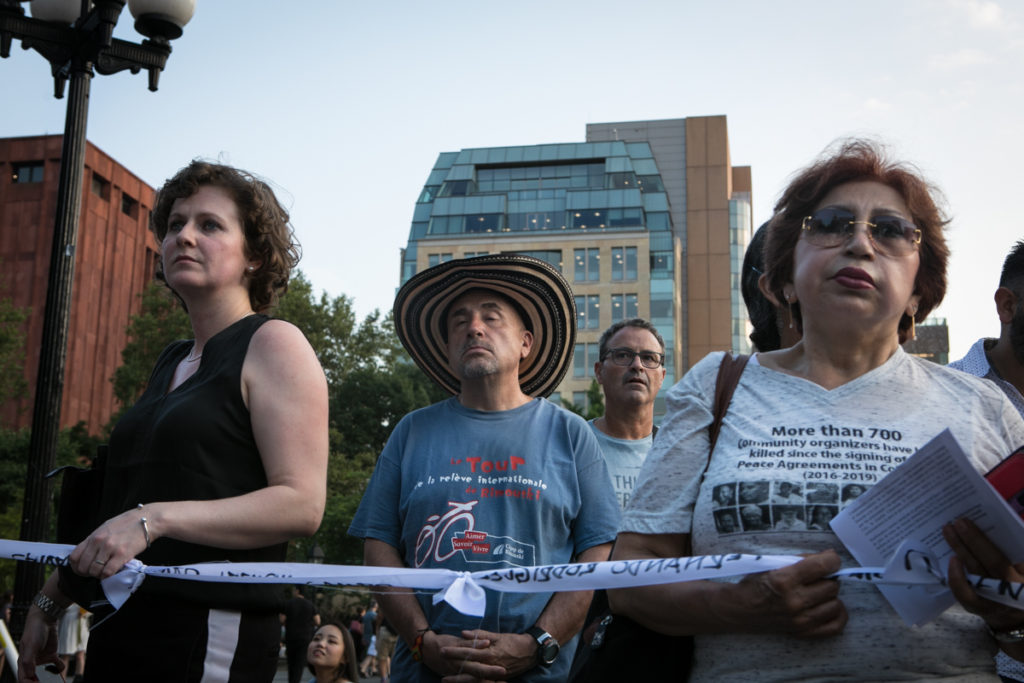

Women watch speakers as they read the names of victims and describe the ways that they were killed. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

The tide of assassinations first began to swell in 2016, when the Colombian government established a historic peace accord with the FARC rebel group and then a public referendum narrowly struck it down. After substantial revisions and implementation failures, armed groups have resurged.

Colombia’s current president, Duque, belongs to the political constituency that most vehemently opposed the peace deal and pushed aggressive propaganda to sell the “no” vote. Since assuming office in June 2018, Duque has taken strides to further dismantle key aspects of the agreement and block negotiations with Colombia’s second largest guerrilla organization, the National Liberation Army, also known as the ELN. Although the president claims that the rate of social leader murders has declined during his tenure, that suggestion is widely disputed, even by Human Rights Watch. The institutional measures his government has put forward to protect leaders have not succeeded. Many people believe Duque’s administration is enabling — if not actively complicit in — the violence.

That perception, in large part, stems from the legacy of the man responsible for Duque’s rise to power, former president Álvaro Uribe Velez, who governed Colombia from 2002 to 2010. Uribe championed an iron-fist ruling style to wipe out the guerrilla. It was so distinct it now has a name: Uribismo. Paramilitarism exploded under Uribe. Now that he effectively rules again with his hand-picked candidate in power — what some people consider a puppet-master relationship — they have resurfaced with renewed strength. Paramilitary forces carry out many of the killings against land defenders and leaders working to implement the peace accord. With Uribe and his cohort at the helm of the opposition against the peace agreement, outrage about the administration’s culpability is at a boiling point. A giant banner in Washington Square Park read, “Uribe es un Matón” — “Uribe is a murderer.”

Musicians play classic Colombian songs in front of a sign critiquing former President Álvaro Uribe. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

Bold signs at the protest make pleas to end social leader assassinations. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

In January, Colombia’s attorney general characterized the violence as “systematic” after a newly released study substantiated known patterns of who is being exterminated. It suggested that the people who are most vulnerable to attack belong to Community Action Boards, known by the acronym JAC in Spanish, which are local-level councils that organize on behalf of the communities they represent. The most targeted organizations are those that pose any grassroots resistance to big business. That includes environmental activists attempting to block development projects, like Goldman Prize winner Francia Marquez, who survived an assassination attempt in May.

People carrying out peace efforts are equally at risk of violence. Part of the peace agreement outlined a plan for land restitution and transitioning from illegal crops to legal ones. Tremendous profit is at stake in that process. It disrupts existing power structures by redistributing territory formerly inhabited by the guerrilla and removing coca, the base plant ingredient of cocaine. As armed groups stake out who fills the power vacuum left by the demobilized FARC, violence has surged.

Strong resistance to the peace process and the proliferation of armed groups that have emerged are part of the equation, but they don’t account for the phenomenon at large. Hundreds of victims have no relationship whatsoever to these efforts. Many people consider the wave of assassinations part of a concerted, structural project that has existed for decades to suppress social organizing and wipe out movements that challenge the ruling status quo. Darío José Mejía Montalvo, a leader from the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC) who survived an assassination attempt in March, sees the killings as a symptom of a much more insidious challenge for communities in Colombia.

“The violence isn’t the cause of the problems,” Montalvo said in an interview. “It is the process by which certain sectors of society are protecting their interests to concentrate land property or develop an economic model that permits narcotrafficking. That includes our politicians and the international financial sector.”

A man at the Grito protest in Washington Square Park wears a traditional Colombian hat. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

A woman solemnly holds part of the chain of victims below the park’s historic arch. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

Indigenous organizations, like the one Montalvo belongs to, have withstood systematic assassinations to their leadership for decades. Their grassroots strength and successful land recovery represent a threat to the interest groups Montalvo described, and the recent uptick of killings still victimizes them disproportionately. Other minority leaders from campesino and Afro-descendent communities have also suffered some of the highest death tolls. All of these groups tend to live in rural areas most affected by the armed conflict, where the failures of the peace process have led to a proliferation of armed groups. In the state of Cauca, the birthplace of the largest and oldest Indigenous organization in Colombia, The Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC), more leaders have been murdered than any other part of the country. Between Aug. 1 and 4, two CRIC activists in the north of Cauca were assassinated. For the Indigenous movement in Cauca, this tide of annihilation belongs to a centuries-long arc of violence. While the specific motivations and character of extermination have changed, the need to resist it has existed for generations.

A man on the street in Cauca, Colombia, wears the bandana of the CRIC wrapped around his face while the organization’s flag flaps in front of him. The CRIC flag reads, “Unity, Land, and Culture” — central values of the Indigenous movement. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

Following this tradition of resistance, the CRIC launched the mass highway mobilization in March alongside more than a dozen minority movements. Afro-descendent and campesino groups united on an unprecedented scale with common frustrations about rising violence and state neglect. Leaders from the council sent a letter to Duque inviting him into dialogue to discuss this issue and others, like minorities’ exclusion from the national development plan. When he neglected their offer on March 11, over 10,000 people descended upon the Pan-American Highway outside of Caldono, Cauca, and shut down the core passage of the continent that connects Colombia to all countries south of it. Demonstrators vowed to uphold the blockades until the president engage them in conversation. They withstood a constant barrage of tear gas explosions, gunfire, rubber bullets and aggressions by federal police, never losing resolve to force the government to address their collective demands.

“What we are asking for is simple,” an Indigenous spiritual mayor, or elder, said at the protest in Cauca. “The right to defend our territory, the right to peace, the right to life itself.”

Demonstrators sit on cinder blocks and sand bags that are part of blockades on the Pan-American Highway in March. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

Protesters sit on a bridge leading to the demonstration, where graffiti reads, “The people rule and the government obeys … Peace.” (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

Sand bags dispersed along the highway create barricades to block the passage of vehicles. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

By the time the president acquiesced on April 9, “The Minga for the Defense of Life, Peace, Territory, Democracy and Justice,” as organizers titled the effort, had drawn nearly 20,000 participants, all of them undeterred by — or galvanized to resist — extreme state violence. The more that riot police abused protesters, burning down their encampments, beating them up and directly firing on them, the more people joined the demonstration. By its conclusion, the minga had marshaled support from 33 congressmen and hundreds of organizations and blockades had proliferated into 12 states throughout Colombia. Now, four months after the minga’s conclusion, The Cry for Life is reinforcing the same spirit of unified resistance and solidarity. As the social leader murder tally rises, so too does the number of people around the world decrying it.

Peaceful protesters flee tear gas explosions on the highway. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

A protester observes a crowd congregating in the distance. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

Dozens of people surround an injured protester on the ground being resuscitated by first responders. More than 10 mingueros died and over 100 were injured during the month-long demonstration. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

“What they’re seeking is to intimidate us — that we become filled with fear,” Giovanni Yule, a CRIC leader, said in an interview. “But they are the ones who are scared that the Colombian people rise up and demand our freedom, our rights and the possibility of governance with transparency.”

The fallout of the minga seems to support Yule’s reading. On April 9, Duque was set to meet mingueros in Caldono, Cauca, forced to placate their request for dialogue after militarized efforts to disband the demonstration had failed, but he never showed. Yule suspects that the president’s absence was not a question of security concerns, as his representatives had cited, but fear about facing the seething anger and demands of the people.

A group of mingueros stand on the highway with their faces covered. Protesters tried to protect themselves from tear gas and remain anonymous to avoid being criminalized. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

One protester holds a rock for self defense as riot police lash out against people in the distance. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

Despite the anticlimactic finale, minga leaders consider the effort an ongoing process of popular organizing and daily resistance that has no end. “Minga” is a Quechua word that refers to any collective, community effort. With resistance now crossing borders in the July protest, that project is growing.

“What they don’t realize is that by trying to intimidate us, they are doing the opposite,” Yule said. “When we see that there is a collective response, that we back each other up as a community, that we are always ready for whatever happens, this gives us so much more strength to keep going.”

A man at the minga stands firm against the encroaching threats in the distance. He wears a bag that says “Colombia.” (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

Protesters return home at sunset beside a fire on the pavement generating smoke to block the effects of tear gas. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

A protester rests in the shade of a tree by the highway, holding his shield made from a road sign. (Photo by Hanna Wallis)

1 Comment

Very informative article.

Comments are closed.