Dispatches, Features, North America, United States

Undocumented Day Laborers Struggle During Coronavirus Crisis

April 30, 2020 By Jose Luis Martinez

HOUSTON—Be Someone. Everyone from Houston recognizes the iconic graffiti sprayed on the side of a railroad bridge downtown. Houston is a place where people flock to “be someone.” It is the most diverse city in the United States. Now, the streets below the railway are empty as COVID-19 brings the city to a halt.

As of April 30, there are 6,161 confirmed cases of the coronavirus in Harris County, where Houston is located, included recovered patients. 109 people have died from COVID-19 in Harris County, according to health officials. In Texas, the stay-at-home order, in place since March, expires today, April 30. Businesses were forced to close in Houston and around the state, but construction, considered an essential business, continued during the shutdown.

Jornaleros, as day laborers are called in Spanish, are used to uncertainty. But the coronavirus has taken away what semblance of routine they had. Instead of working for a labor staffing agency, jornaleros wait for work by standing at esquinas, the Spanish word for corners, where they wait for contractors to pick them up. Most jornaleros in Houston are undocumented and come from Central America and Mexico, while a few come from Africa and Cuba. As the economic recession sets in, jornaleros are wondering when their next pay day will come.

Jornaleros are people who undertake daily or temporary work in unpromising situations. They live in a cycle of anxiety and uncertainty. Jornaleros in the city of Houston in the state of Texas are trying to keep up hope despite the COVID-19 crisis.

There is no exact count of jornaleros in Houston, but there are over a dozen esquinas at Home Depots and gas stations, where usually more than a dozen jornaleros gather each day. Due to the fear of the virus propagating, contractors are not arriving at the esquinas to provide labor opportunities.

Latin Dispatch spoke to Eduardo, Álvaro, and Luis, three jornaleros in the Houston area. Their names have been changed due to their undocumented status.

“The corners have vanished” says Eduardo, who is one of few who still sometimes seeks work, out of necessity to provide for his 16-year-old daughter. Luis notes that recently at the esquinas, “they only hired one man” for the entire day, leaving behind dozens of jornaleros without work.

Eduardo was born in Honduras. By the time he was 19, a gang had killed his brother, and his girlfriend was shot in the back. He left Honduras and came to Houston, where he has been a jornalero for the past 17 years.

Eduardo has been injured while working, after which the contractor denied he knew him. His wages have been stolen. When he tries to recover stolen wages, the contractors stop picking up his calls. When he manages to get work, the contractors do not provide safety gear such as helmets or gloves.

The crisis caught his family by surprise, like a “balde de agua fría,” a bucket of cold water, and he has not worked since March 23. When asked what he plans to do in case the lockdown is extended, he responded, “We’re in God’s hands…we commend ourselves to God.”

Álvaro migrated to the United States in his forties. He grew up in Mexico City, and tried to make it as a professional soccer player. Then he became a welder and later worked with the government. However, economic stagnation lowered his wages and he left Mexico for Houston in 2001. Álvaro migrated with his wife to work and send money to the five children they left behind.

During 12 years as a jornalero, Álvaro has been threatened with a firearm. His wages have been stolen countless times. He communicates with some contractors through a translation app so they cannot take advantage of him. If someone disrespects him, he simply leaves the job. While at work, he streams Mexican soccer games through his phone and cheers for Cruz Azul, a nostalgic reminder of his younger days.

The last time he was at the esquinas was a month ago. Now his only relief is that his landlord is not making him pay rent during the crisis.

Luis was a ranch worker who cared for cows in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico. He came to the United States for a better future. Luis left behind six children. But after 15 years, he has realized that “if one doesn’t have papers, it’s the same or worse” in the United States.

After arriving in Houston, Luis says contractors threatened to call immigration on him and that he is not able to say anything because he is undocumented. He has had his wages stolen. Even now, during the coronavirus crisis, a contractor owes him money. The contractor is not answering his calls. The last time he worked was mid-March.

Because many jornaleros are undocumented, they have no source of income if contractors stop hiring. They are not able to apply to other jobs legally since they do not have social security numbers. During the pandemic, other jobs that pay in cash are unavailable. That means that the jornaleros in Houston, and their families abroad who depend on them, will struggle to meet basic needs.

Álvaro has managed to survive through a colchoncito, a little cushion, of savings he has been building up through the years. Those savings, however, are temporary and will not sustain the jornaleros for long. Luis says that in apartments where four jornaleros used to live, there are now eight jornaleros living in them just to be able to pay rent.

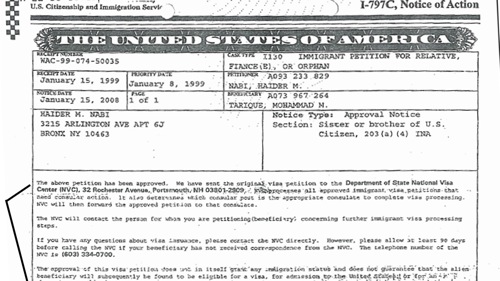

Photographed in 2019, Jornaleros gather at meeting points known as “corners,” often near gas stations or Home Depots, where they wait for contractors to arrive. Photo by José Luis Martínez.

A common misconception is that undocumented immigrants do not pay taxes. While it is not a form of employment authorization, undocumented immigrants have the option to get an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) which allows them to file tax returns and claim certain tax credits. The American Immigration Council reported that “According to the IRS, in 2015, 4.35 million people paid over 13.7 billion in net taxes using an ITIN.”

Despite these contributions, ITIN holders cannot claim unemployment in Texas and receive the benefits being offered during the COVID-19 crisis. In Houston, just two weeks after businesses began to close, more than 400,000 Texans filed applications for benefits, according to the Houston Chronicle. Jornaleros will not be able to apply to receive temporary relief and must turn elsewhere.

Federal government stimulus checks are another effort to cushion the economic effect of the pandemic that undocumented workers do not qualify for. Taxpayers who have an ITIN number do not qualify for the checks. Jornaleros are ineligible for state and federal help even if they pay taxes.

“In times of crisis, poor and rich should be equal…this feels like racism” says Eduardo.

Álvaro wishes that the government would at least consider sending undocumented immigrants some aid, even if not the full amount legal residents and citizens receive. He wishes the government would at least offer a work permit. Luis said that the local and federal government should remember that jornaleros make the country strong.

As part of the stay-at-home order which banned gatherings, local law enforcement in Harris County can also impose jail time or fines to those who violate the order, although traveling to work and grocery shopping are exempted. This results in greater scrutiny over who can drive on the roads. These measures pose a threat to undocumented immigrants who fear that they may be detained and questioned about their immigration status.

In 2018, a federal appeals court upheld portions of Texas Senate Bill 4, also known as SB4, which allows local law enforcement discretion on whether to collaborate with Immigration Customs Enforcement (ICE) or to ask an individual about their immigration status.

These measures discourage jornaleros from leaving their home to get necessities or seek out alternative sources of income. Jail time or fines would be problematic for undocumented immigrants who hope to to apply for residency or citizenship in the future.

Another impediment is the lack of health insurance. Since jornaleros are undocumented, they do not have access to timely and cost-effective healthcare. The fear of enormous hospital costs may prevent some jornaleros from going to be treated for COVID-19 in case they tested positive. The Trump administration says that immigration authorities will not target hospitals or ask for immigration status while getting tested for the virus. Jornaleros expressed that they “have no other choice” but to go to the hospital if they get sick, but that fear persists.

At the federal level, there have been efforts to support undocumented workers. Latino lawmakers are urging congressional leaders to provide economic support to the nation’s farmworkers. Organizers around the nation are requesting that the government provide Temporary Protected Status (TPS) to migrant essential workers. In California, Governor Newsom announced that undocumented immigrants will receive a one-time payment of $500 due to the crisis.

In Texas, no policy measures have been taken to provide relief or economic assistance to undocumented immigrants. Harris County Judge, Lina Hidalgo, said that inclusive recovery will take undocumented workers into account, but no specific measures have been announced. A non-profit in Houston, The Faith and Justice Worker Center, is taking online donations. The Center is distributing work equipment such as gloves and masks and hosting online information sessions to inform workers about their rights during the crisis. The consulates in Houston from Guatemala, Mexico, and El Salvador provide information about access to local food banks and other independent resources.

Jornaleros still have plans for their future. Álvaro plans to go back to Mexico to reunite with his kids at the end of this year. He says that the Latino community has to “Echarle ganas,” which means “Work hard.” Eduardo says his faith in God is helping him during the crisis. One day Luis hopes to get a license to be an electrician or plumber.

In the meantime, Houston’s jornaleros are waiting and hoping to get back to work.

Special thanks to the Faith and Justice Worker Center, which coordinated interviews with jornaleros. The Center, called Centro de Fe y Justicia in Spanish, is a worker’s rights community center in Houston that helps mobilize campaigns, provide wage-theft case resolution services, and builds a peer-support network.