Central America, Costa Rica, Dispatches, Features

In Costa Rica, Defending Indigenous Territory Comes at a Price

May 27, 2020 By susannes

Across Latin America, Indigenous territories are particularly vulnerable to the coronavirus. In Costa Rica, public health measures have largely prevented infections among the Indigenous population. But for Indigenous territories like Térraba, in the Puntarenas province, other dangers remain. Even when the coronavirus shutdown ends, the threat of violence against Indigenous people defending their land will continue.

Costa Rican human rights defender Jehry River Rivera was murdered on February 24 in Térraba, over landownership disputes between Indigenous people and non-indigenous peasants. This murder is reflective of a larger pattern of violence in the Bribri and Bröran territories over landownership disputes. A year earlier on March 19, 2019, Sergio Rojos Ortiz, leader of the Bribri Indigenous movement, was killed in his home in Salitre, which is also in the Puntarenas province. In both cases, community members have identified the perpetrators but to this day authorities have not prosecuted the crimes.

When Indigenous communities attempt to recover land that legally belongs to them in the Térraba territory, they are often met with violence. Currently, over 50 percent of their ancestral land is illegally occupied by non-indigenous people. The Bribri and Bröran people must endure physical violence. The illegal occupants have also initiated large-scale burning of peacefully recuperated farmland, which is harmful to their livelihoods and detrimental for the environment. The Inter American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), an autonomous organ of the Organization of American States, has expressed concern for the situation for Indigenous leaders, and human rights and environmental defenders in Costa Rica now for many years.

“No one would think that Costa Rica has problems. But we know that’s not true, especially when it comes to Indigenous people,” says Vanessa Jiménez, Senior Attorney at the United Nations Human Rights Watch’s Forest Peoples Programme, who has been working in Térraba since 2012. “If you can’t get Costa Rica, which is where the American Convention on Human Rights was signed, to protect human rights or environmental defenders, how are you going to protect them in Honduras, and in Ecuador, and in Brazil?”

Costa Rica’s 1977 Indigenous Act recognizes 24 indigenous territories that are protected for people with historical ties to the area. In March 2016, the Costa Rican government issued the Indigenous Territories Recovery Plan (El Plan de Recuperación de Territorios Indígenas) to follow up on the implementation of this act after decades of inaction. But there has been limited progress, according to Jiménez. She says the first step is to survey who in the territory is Indigenous, to recognize their land rights.

Those who do not have a claim to the land would be removed, but there is no procedure established to carry out these removals. So far, when eviction orders are issued for these areas, the settlers immediately appeal. The cases get stuck in the judiciary, so the government never carries out the evictions.

“The violence happens, because there is no removal,” says Jiménez. “This has been known for decades, and the illegal occupation continues.”

According to local sources, messages circulated in a community WhatsAppp group the day before Rivera was killed, informing the public and the government that an angry mob of non-indigenous people was planning to attack Térraba. The government did not act to prepare police patrols and help Rivera’s community.

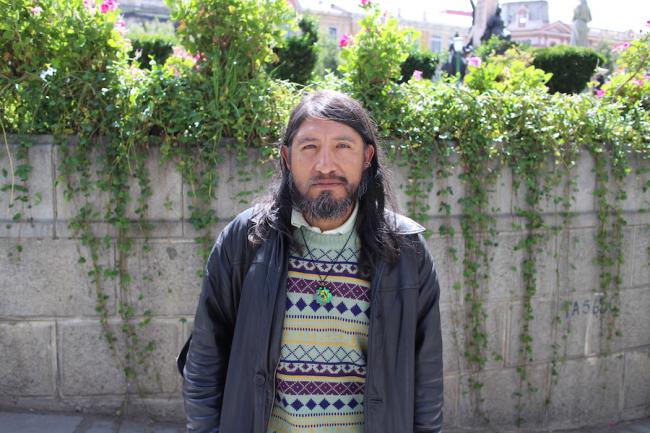

Paulino Najera Rivera, who also lives in Buenos Aires, reflects on the day of the murder, recalling the noise of motorcycles and people screaming and calling out death threats, in what is usually a peaceful and quiet town.

“They were screaming and screaming,” he says. “Everybody was panicking. A lot of people did not understand what was going on. The police were very passive.”

Najera Rivera knows Rivera’s family, which was at the forefront of the indigenous fight for development and recuperation. Someone turned himself into the police, confessing to shooting Rivera, claiming it was self-defense. He was later released.

“The community is frightened. If such a thing can happen twice, first to Sergio, then to Jerrhy, it might happen again. It might happen to anybody,” Najera Rivera says.

Rivera and Najera Rivera were actively working together for joint goals. Najera Rivera says, “We always talked about the indigenous fight. [Rivera] knew the contracts and the laws very well.”

Najera Rivera was also a close friend of Ortiz, who was killed in 2019. Three days before Ortiz’s death they had been chatting in the center of Buenos Aires, Najera Rivera recalls, “He told me, ‘I am not afraid of dying, if I die, I die. I am always going to tell the truth. The most important part is the ideals we fight for. And our fight is justified.’”

The documented cases of violence and threats in Terraba continue with impunity. In February, Bribri member Mainor Ortíz Delgado was the victim of the third shooting directed against his family by the same perpetrators. He was shot in the right leg, and his attacker was set free less than 24 hours after the attack.

In 2013, non-indigenous men shot at Delgado, and attacked him with a machete. The perpetrators of the recent attack on him and his family live next door and all belong to the same family. Every time Delgado plants new crops and tries to rebuild his land, these people come and burn down the harvest.

“Nothing has happened, nothing has gone in our favor. [In Salitre] we live in fear,” Delgado says.

The IACHR issued precautionary measures in 2015, urging the Costa Rican government “to protect the lives and physical integrity” of the Bribri and Brörán communities. Ortiz was supposed to be protected under these precautionary measures, which include increased police presence, a hotline to document violence and threats in the region and punishing those responsible for the attacks. Despite the issuance of these precautionary measures, there was no implementation. To Delgado, the murders of “his brothers” have demonstrated that the court’s precautionary orders have done nothing to protect their lives and physical integrity.

Jiménez says that since she started doing her work in Costa Rica in 2012, there have been hundreds of cases of horrible violence against indigenous people and activists. “In 95% of the cases, no one’s ever been sanctioned at all. The 5% is where someone has gotten a slap on the wrist,” Jiménez says. “Considering this amount of impunity, it doesn’t come as a surprise that these acts of violence, often committed by the very same perpetrators, keep happening.”

A large part of this discrimination against Indigenous communities is due to stereotypes and racism. Pablo Sivas Sivas, who is a leader of the Bröran people, says, “A lot of Indigenous people don’t take a stand, because they think it’s the white people who have rights. Because they have the money, they can afford the lawyers, they can win the judicial process.”

Lesner Figueroa Lazaro, who is the Legal and Policy Coordinator for the Bribri people, reflects on how the government has failed to comply with indigenous law and protection, causing the current state of violence in the region. He regards impunity as the greatest problem. To Lazaro, the Costa Rican state recognizes Indigenous land and Indigenous rights on paper but does not enforce them. “If there are acts of violence it’s always us, the Indigenous, who are violent, who are aggressive. It’s always the Indigenous who engage in unlawful acts. All that would have to be done is to actually apply what’s written on paper,” Lazaro says.

A large public protest took place on February 28 after Jerhy’s murder. Members of Indigenous communities united to protest his death and the violation of their landownership rights, hoping to finally be heard by their government.

When asked about this united action and his hopes for the future of Térraba’s Indigenous population, Najera Rivera seems hopeful that justice will ultimately reign. “When we initiated the recuperation process forty years ago… …It was very hard, there were no laws in place yet,” he says. “But today forty years later, we can see that our work paid off and has shown results. It’s like planting a tree, first the seed turns into a small plant, and years later there is a large, enormous tree.”

Like Najera Rivera, Indigenous activists in Puntarenas remain hopeful. Delgado says, “This is a fight and no fight is easy. The only way this can change is if the state applies the laws as they are written and gives us our lands back.”

Banner photo via Flickr.