Brazil, Dispatches, Features, Southern Cone

Coronavirus Cases Rise in Brazil’s Overcrowded Prisons

June 30, 2020 By Staff

By Bruna Lima and Isabelle Xavier

RIO DE JANEIRO— Efforts to prevent the novel coronavirus from entering the Brazilian prison system failed. Now, health workers are struggling to prevent mass infections, among a prison population already at risk for infectious diseases.

Juliana, who asked her name be changed, is a nurse technician working on an itinerant team created to face the COVID-19 pandemic inside Rio de Janeiro prisons. Twice a week she leaves home and begins her journey to the detention centers.

The number of cases is increasing quickly. On June 23, the Rio de Janeiro State Secretariat of Penitentiary Administration reported 30 new cases. Just two days later, the entity disclosed 79 more cases for a total of 109, including 12 deaths. However, the true number is likely higher, due to low testing rates in the prisons.

Juliana says she is tired of witnessing inhumane treatment. After more than two decades working in the system, she hopes to retire soon. “Sometimes I feel like nothing I do will ever help,” she says.

Unattainable Recommendations

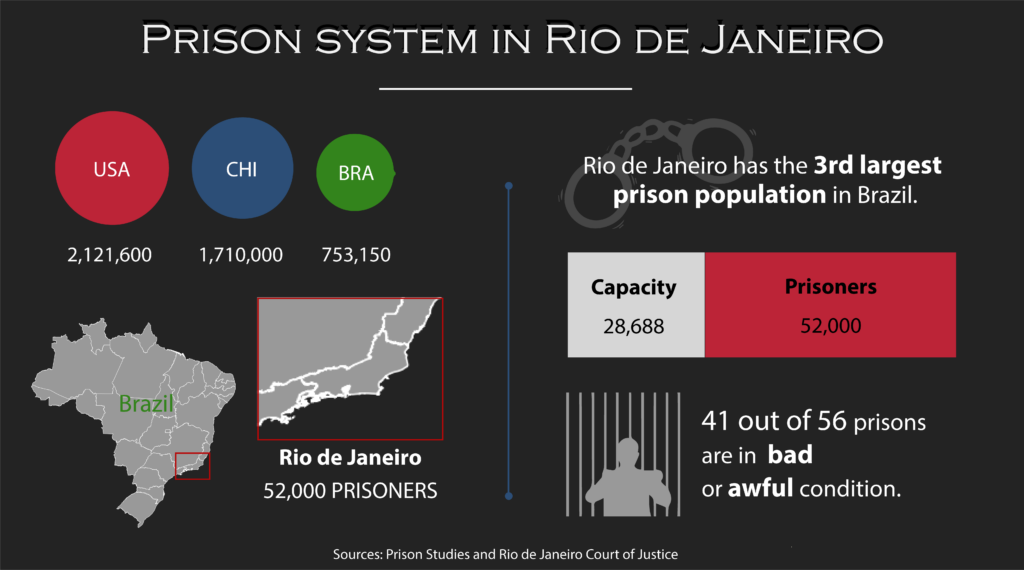

COVID-19 highlights ongoing problems in the Brazilian prison system: overcrowding, unhealthy conditions, difficulty in accessing health care, lack of transparency, and neglect. According to the State Mechanism to Prevent and Combat Torture, from the beginning of March to May 20, the prison system recorded a total of 54 deaths from unknown causes, double the total during January and February 2020. This increase coincides with the beginning of the pandemic in the state of Rio de Janeiro.

To prevent the spread of COVID-19, the Ministry of Health presented the Brazilian population with guidelines based on the World Health Organization’s recommendations. The guidelines call for prisons to maintain distances of at least six feet between individuals, without taking into account the reality inside. The government guidelines to fight the new coronavirus are impossible to implement inside prisons.

Keeping indoor spaces ventilated and improving respiratory hygiene are other recommendations. “The cells are usually designed for 80 or 90 inmates, but in most units there are well over a hundred [inmates per cell],” says Juliana. “It is impossible to maintain an airy environment.”

Murilo Bustamante, of the Public Prosecutor’s Office for Collective Guardianship of the Prison System and Human Rights, says the biggest challenge is prison overcrowding.

Monique Cruz, PhD in Social Work and a member of the human rights organization Global Justice, emphasizes that the Rio de Janeiro prison system does not guarantee basic legal rights for incarcerated people.

“When the state imprisons someone, it assumes responsibility for preserving that person’s life. But what we’re seeing is a scenario of violation,” says Cruz. “It is not possible to face this pandemic, this type of disease, the way it spreads, contaminates and kills, in the conditions of Brazilian prison units. People are being left to die.”

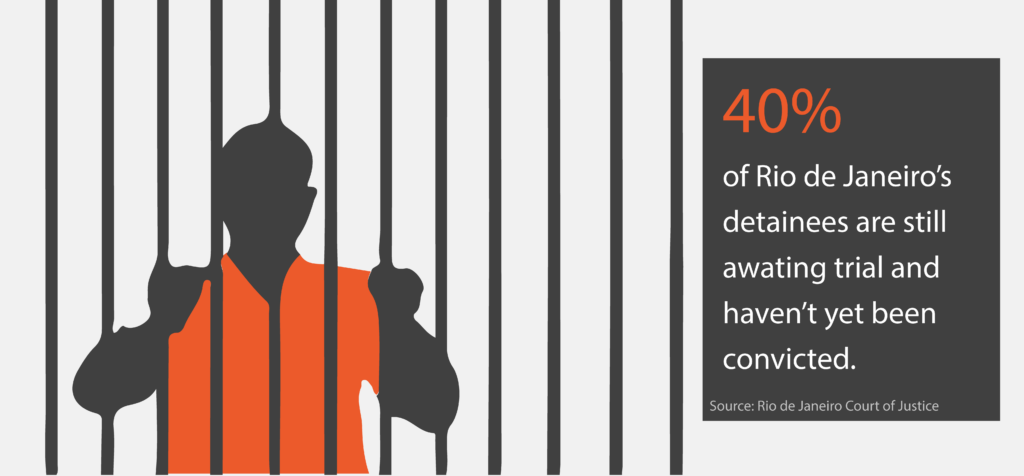

One of the recommendations of the National Council of Justice is to reevaluate pretrial detentions. This measure seeks to relieve, even if slightly, overcrowding in prisons. However, some judges argue that incarcerated people are better protected from the virus inside prisons.

Former Minister of Justice and Security, Sergio Moro, and President Jair Bolsonaro both say that the pandemic should not be a pretext to release incarcerated people. More than 40% of people in Rio de Janeiro’s prisons are pre-trial detainees, that is, they are awaiting trial and have not been convicted.

Rafaela Albergaria, member of the State Mechanism to Prevent and Combat Torture, says it is converning to have judges and politicians argue that incarcerated people are safer inside prisons. “They know that it is not feasible to follow the measures proposed by health institutions. It’s clear that is a policy of leaving [the inmates] there to die,” she said. Failing to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in prisons is a form of necropolitics, when the state chooses who should live and who should be left to die.

Prosecutor Murilo Bustamante says the situation is critical. To solve it, the prosecutor says would require collaboration across different spheres of the government, including the health and judiciary secretariats. “I see that many efforts are being made, but they are not enough and the situation is becoming more urgent,” he says.

“Doctors in the system are a luxury item”

The outpatient clinic of each prison unit has the duty to identify incarcerated people who have symptoms related to coronavirus and put them in isolation cells. Only doctors who work at the outpatient clinic can provide diagnosis and referral for treatment in the prison hospital.

“Doctors in the system are luxury item,” Juliana says. The State Secretariat of Penitentiary Administration created an itinerant health team for the pandemic period to address the shortage.

The traveling heath team assists as many prisons as possible during the day and monitors the inmates isolated for suspected COVID-19. According to Juliana, the health professionals are divided into groups of two nurse technicians and one nurse.

The traveling team only has four doctors, not nearly enough to make up for the shortage. There are not enough doctors to assist every prison, so they do not usually accompany the nurse technicians and only attend to severe cases.

The symptoms of the new coronavirus are similar to those of asthma, tuberculosis, respiratory syndromes, and common flu. Juliana believes that some inmates are being treated as suspected COVID-19, but actually have tuberculosis. Tuberculosis is the main cause of death from infectious disease in the Brazilian prison system.”Sometimes the person is considered a COVID-19 patient and isolated with other inmates who are symptomatic. And then when you see it, tuberculosis has already done a lot of damage,” she says.

Rafaela Albergaria of the State Mechanism to Prevent and Combat Torture says that the lack of doctors inside prisons to make proper diagnoses and refer patients to treatment is dire. She says the nurses and nurse technicians who work at prison outpatient clinics are not able to distinguish between symptoms of coronavirus, tuberculosis or common flu, causing improper isolation, and increasing the spread of the virus.

Before the pandemic, incarcerated people in Rio de Janeiro already considered isolation a form of punishment. Now people suspected of having COVID-19 are being isolated with others undergoing treatment for different infectious diseases. The situation only reinforces the idea of isolation as punishment.

The COVID-19 swab test is available at the prison hospital only for inmates who have severe symptoms and have been referred by doctors, or for the deceased. The hospital’s emergency room only has five swabs to perform the tests.

Incomplete case numbers

Mass testing of detainees would aid in proper isolation measures and timely identification of cases. The State Secretariat of Penitentiary Administration notified in its latest bulletin, updated on June 25, that 109 detainees in Rio de Janeiro prisons tested positive for the new coronavirus, 12 have died of COVID-19, and 97 are stable.

Speaking to Juliana on May 21, when the Secretariat had only reported 11 cases of COVID-19, she expressed doubt in the official figures. “That’s a lie. In the hospital alone there were a lot of cases, and everything got contaminated after the first deaths,” she said.

The Public Defender’s Office of Rio filed a Public Civil Action case alleging that at least 14 additional deaths between March and April should have been classified as suspected COVID-19.

By disclosing only the cases and deaths confirmed by the swab test, authorities are concealing the true scope of the pandemic inside the prisons. COVID-19 presents an urgent risk to incarcerated people, and is exposing deep-seated problems within the prison system. The government has not yet made real efforts to help the prison population, which has been forgotten and neglected for years.

“A lot of people don’t understand that I look at the prisoner as a human being. If he is in jail, he doesn’t owe the society anything else,” says Juliana. “Fighting for their dignity in the system is exhausting.”

Bruna Lima is an undergraduate journalism student at ESPM-Rio, in Brazil. She is currently an intern at the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism and has been covering freedom of expression and violence against journalists in Brazil.