Dispatches, Features, Topics

Corruption levels in 2022 largely unchanged across Latin America

February 3, 2023 By Staff

NEW YORK — The level of perceived public sector corruption in the Americas has remained stagnant for several years in a row, with 27 out of 32 countries having unchanged levels since 2016.

The findings come from the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2022, a report published on Tuesday by Transparency International, a global anti-corruption organization. The CPI gathers data from businesspeople and country experts that indicate several factors of a country’s well being, including government transparency in the access of information, the rule of law and the extent of civil society, among others. It then uses the information to assign each country a score from zero (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean) on the perceived level of corruption in each country. The average for the Americas was a low score of 43.

The worst performing countries were Venezuela, Haiti and Nicaragua, with scores of 14, 17 and 19, respectively. Honduras and Guatemala also performed poorly, with scores of 23 and 24 respectively.

Luciana Torchiaro, regional advisor for Latin America and the Caribbean at Transparency International, told LAND, “The findings reflect that the countries are not doing enough to tackle corruption.”

Torchiaro said that most of the countries in the region have strong anti-corruption laws and have participated in global fora with anti-corruption commitments like the Summit of the Americas or the Open Government Partnership. “But they are not delivering on those commitments,” said Torchiaro. “Corruption is not at the top of the agenda at the moment in the region.”

Corruption: History and Consequences in Latin America

Corruption is broadly defined as the misuse of public office for purposes other than the public good. It can occur at the level of high-ranking public officials, known as grand corruption, or at a smaller level, known as petty corruption.

At the heart of corruption often lies the transfer of large sums of money that has been illegally obtained. It can look like corporations or illegal organizations bribing politicians with money in exchange for policy that benefits their business. It can also look like public servants funneling state money into personal accounts. Bottom line, corruption allows perpetrators to advance personal gain through illegitimate means.

The most recent large-scale corruption scandal in the region’s history involved Odebrecht, the largest construction company in Latin America. Over a period of 10 years, Odebrecht paid over US $780 million in bribes to government officials to win favorable construction contracts. As a result, Odebrecht obtained contracts and other favors to the tune of nearly US $3.4 billion.

The Odebrecht scandal had major consequences for leaders across the region.

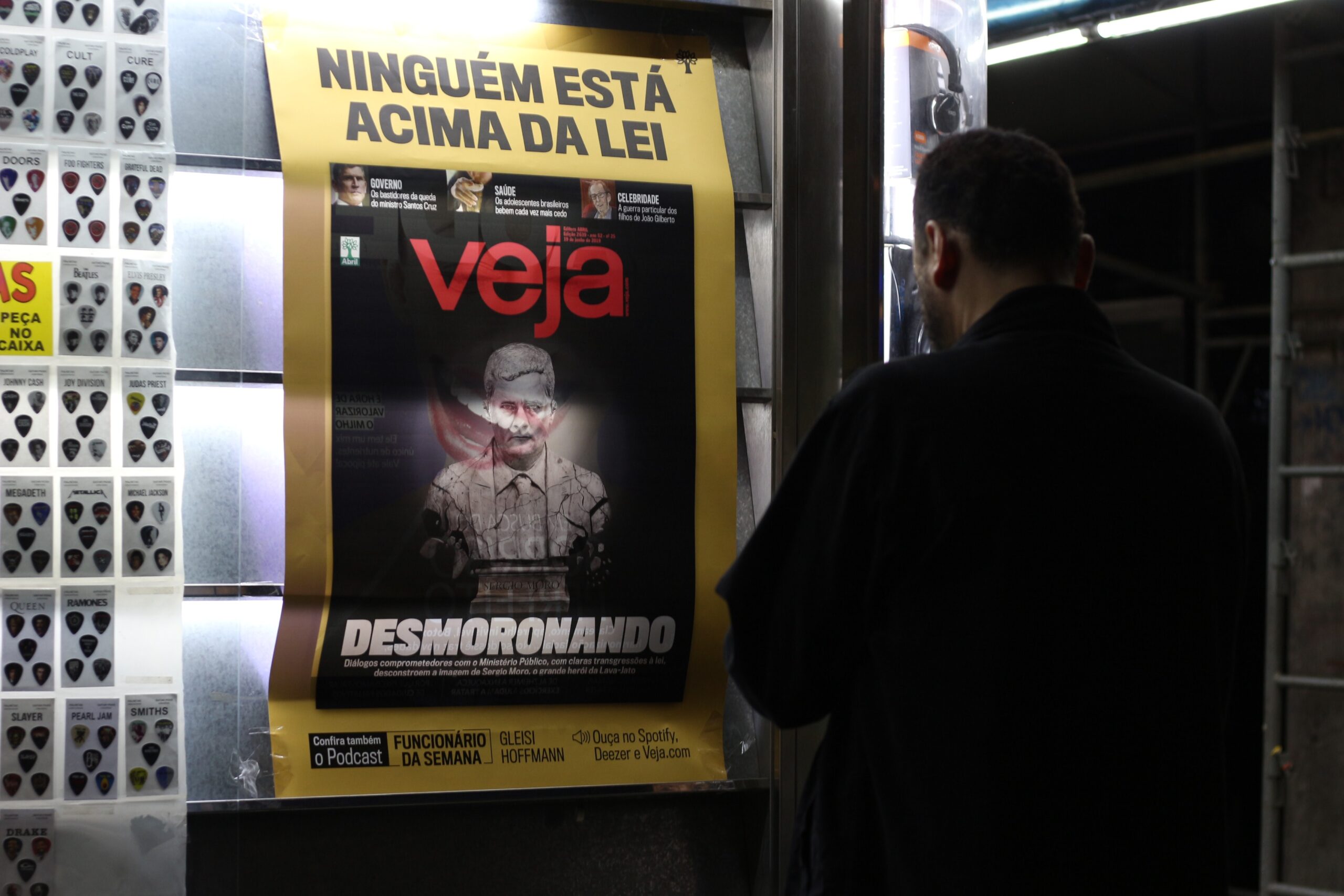

Following the investigation into Odebrecht’s corrupt practices, then-former president of Brazil Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was convicted in 2018 on charges of money laundering and corruption in connection with the scandal. The supreme court judge who presided over Lula’s case, Sergio Moro said, “No matter how important you are, no one is above the law.” Moro’s cases against Lula were annulled on June 24, 2021.

Government officials in Venezuela and in the right-wing government of Ricardo Martinelli in Panama were also implicated in the scandal. During the 2014 election in Colombia, the campaigns of then-President Santos and his competitor Oscar Zuluaga also received money from Odebrecht.

Professor of political science at NYU Patricio Navia told LAND that following the Odebrecht scandal, countries took measures to stop corrupt practices from taking place, but very few people actually went to jail.

“In essence, elites get slapped on the wrist, rather than real penalties or prison time for their corrupt practices,” he said. “That, of course, generates the perception that the justice system is not fair.”

Impunity in the face of corruption further shapes the expectation that the government is not equipped to fight corruption, increasing its perception index.

Navia also told LAND that corruption has specific, negative consequences for a country.

“Corrupt countries tend to have lower degrees of trust in institutions. Democracy doesn’t function quite as well, and there are high inefficiencies,” Navia said. “There is the perception that meritocracy is not the rule of the land, and that who you know and what kind of access you have will determine how successful you can be.”

Is corruption perception enough?

Measuring the actual level of corruption — in terms of the number of corrupt acts taking place or the amount of money being transferred in corrupt transactions — is hard to do because it happens under the radar.

As previously mentioned, Transparency International circumvents this problem by aggregating data from several country indicators.

Is the perception of corruption, however, an adequate proxy for measuring actual levels of corruption?

When asked the question, Torchiaro said, “We believe that the aggregation of these indicators is a good way to measure the levels of corruption in a country.”

But the share of people critical of the CPI is considerable, and they contend that it is misleading and distracting, at best, since it only gauges elite perceptions of corruption and sets aside Transparency International’s other work in fighting corruption.

Other ways of measuring corruption have become standards, as well. In particular, Americas Quarterly and Control Risks releases yearly their Capacity to Combat Corruption which instead of, “measuring perceived levels of corruption, the CCC Index evaluates and ranks countries based on how effectively they are able to combat corruption.”

A representative from Americas Quarterly declined to comment on the differences between its CCC and Transparency’s CPI, only saying that the 2023 CCC would be published in June.

Despite the pushback against corruption perception, experts on corruption still find value in the CPI.

Professor of politics at the University of Sussex, Dan Hough, told the Washington Post, “The CPI helps to keep the fight against corruption on the agendas of policymakers and the global commentariat.” Essentially, the CPI keeps corruption in the minds of decision makers whose choices affect the lives of everyday people.

Reporting for this story was done by Alfredo Eladio Moreno, Kiana Katrisha Paclibon and Marin Scotten.