China, International, United States

The U.S. Is Overstating China’s Influence in Latin America

April 8, 2023 By Miquel Vila Moreno

This story was republished with permission from World Politics Review.

Heightened tensions between the U.S. and China have many observers likening their strategic competition to a geopolitical struggle reminiscent of the Cold War. While the focus of that competition is in Asia, it extends to all the world’s regions, particularly where China has made inroads into what were historically regarded as U.S. spheres of influence, like Latin America.

In recent years, Beijing has established a strong foothold in the region, causing anxiety in Washington about China’s desire to blunt U.S. influence there. These fears have intensified amid the recent resurgence of left-wing and nationalist governments, particularly in South America. China’s demand for Latin American commodities and the region’s demand for Chinese consumer goods are the pillars of this relationship, which is reinforced by shared distrust of the U.S. and a mutual interest in rewriting the rules of the international system. But although Beijing has made considerable gains in the region at Washington’s expense, claims about China’s influence there might be overstated.

Over the past two decades, China has cemented its status as the largest trading partner for the region’s heavyweights like Brazil, Chile and Argentina. In addition, trade between China and Latin America reached an all-time high of $450 billion in 2021, making it the region’s second-largest trading partner, behind the U.S., and South America’s top trading partner.

Last year, too, one estimate suggested that China allocated nearly $10 billion toward investment in the region—including through offshore financial centers—more than what it directs to the considerably larger economies of the U.S. and European Union. That would make China the third-largest source of foreign direct investment for Latin America, and second in terms of mergers and acquisitions.

The majority of China’s investments in Latin America are concentrated in energy, mining and infrastructure. More recently, the growth of the electric vehicle industry and increased demand for lithium has factored into Beijing’s calculations in the region as well. Chinese companies now dominate the mining sector in the “lithium triangle” countries of Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, for instance.

Although China’s power-projection capabilities pale in comparison to the U.S., Beijing is a crucial partner for Washington’s adversaries in the region. China is Venezuela’s main benefactor, with Caracas now the leading importer of Chinese arms in Latin America, and Beijing is deepening cooperation with Cuba as part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Until the early 2000s, the Monroe Doctrine was a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy for over 200 years, premised on Washington’s preeminence as the undisputed hegemon in the Western Hemisphere. Viewed through that prism, China’s growing influence in Latin America poses a threat to the United States’ interests, especially given the number of governments that oppose Washington’s dominance in the region. But despite inroads Beijing has made in Latin America, it cannot be said to have displaced Washington there.

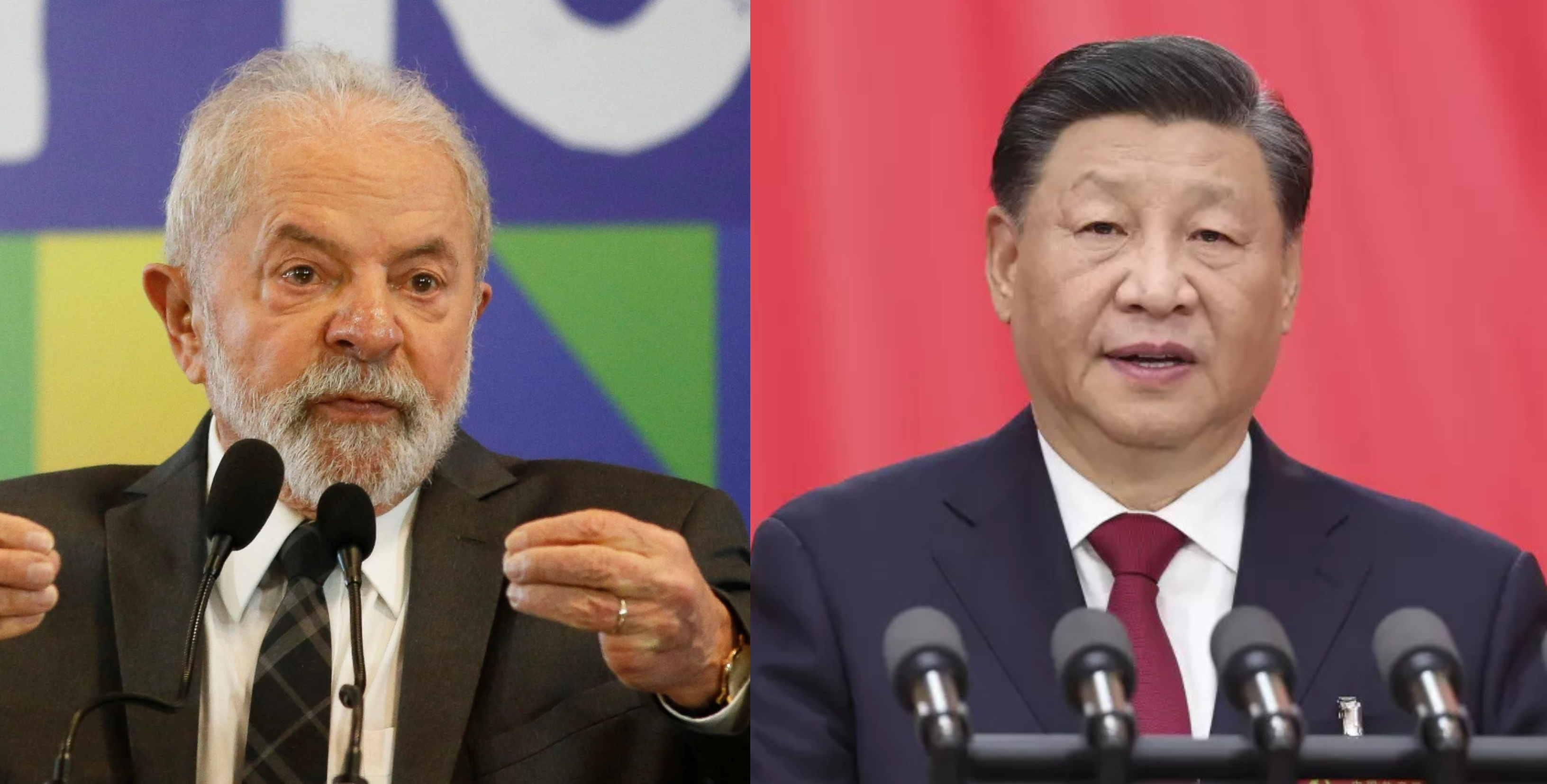

Chinese engagement in Latin America has yielded some political dividends. In the past decade, El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, Panama and Nicaragua have switched their diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing; just two weeks ago, Honduras followed suit. And at the United Nations, Latin American countries have cast votes on a range of issues that have proved valuable to Chinese interests, including a failed effort at the Human Rights Council to open a debate on allegations of human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Bolivia, Cuba and Venezuela voted with China, while Argentina, Brazil and Mexico abstained. Moreover, the resurgence of the left, particularly in South America, could play into China’s hands, given the Latin American left’s historical animosity toward Washington. The return to office of Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, for instance, will undoubtedly boost efforts to counter U.S. influence in the region. During his previous stint in office from 2003 to 2010, Lula demonstrated a preference for close ties with China and worked to revitalize South-South relations in forums like BRICS, an informal grouping of countries that includes Brazil as well as Russia, India, China and South Africa.

But close ties to China, in Brazil and elsewhere, go beyond ideological alignments, even in the case of countries like Cuba, Venezuela and Bolivia. Economic realities across the region mean that changes in government are unlikely to affect trade and commercial relations with China. Indeed, in Uruguay, right-wing President Luis Lacalle Pou is currently negotiating a free-trade deal with China.

Similarly, Lula’s predecessor, former far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, used “tough on China” rhetoric as a candidate during the 2018 election campaign, but once in office, he did nothing to hamper trade with China. Brazilian demand for Chinese goods, services and investments, continued unabated for the four years he was in office. In 2021, Brazil received nearly $6 billion in foreign direct investments from China, while BYD, a Chinese automobile manufacturer, announced plans to open three factories in the country, with a total investment of $565 million.

In addition to China’s imports of commodities and exports of affordable manufactured products to Latin American consumers, it is also opening factories and providing other services that will deepen bilateral relations between Beijing and Latin American governments. In recent years, this engagement has also broadened to involve local authorities and the private sector. This has given way to a deeply entrenched Chinese presence in the region that is more resistant to political fluctuations.

Nevertheless, there is little evidence of an inclination in Latin America toward embracing the so-called Beijing Consensus or accepting China’s aspiration toward a global leadership role. For instance, opinion surveys conducted in 2021 in Mexico and Brazil show that most respondents regard U.S. global leadership as better for their country than China’s. The U.S. is a top destination for migrants from Central and South America, and China will likely be unable to recreate the broad links those communities build. And Chinese culture and language will be hard-pressed to compete with U.S. soft power and cultural hegemony in the region.

The Cold War framework that is commonly used to describe the growing rivalry between China and the U.S. is also historically misplaced. During the actual Cold War, the region’s domestic ideological battles between U.S.-sponsored free-market capitalism and Soviet-sponsored communism corresponded to the broader ideological battle between Washington and Moscow. But while Latin American countries today are profoundly polarized, that polarization does not necessarily map onto a preference for either China or the United States.

The original Cold War also entailed a territorial division of the world into spheres of influence against the backdrop of a militarized confrontation, while marking newly independent nations in the Global South as battlegrounds for geopolitical competition. Today, China might envision an independent trading bloc composed of countries from the Global South, while many in Washington talk about an “economic NATO” and “friend-shoring” among democracies. But most of the countries they might hope to recruit for these blocs are unlikely to accept becoming satellites of either China or the U.S., nor will they be content to view themselves as pawns on a geopolitical chessboard. Global power is more distributed today than it was in the 20th century, with countries like Brazil and Mexico desirous to play a contributing role within the international system.

Finally, a recent piece in The New York Times pointed to the ways Chinese companies are taking advantage of Washington’s nearshoring tactics in Latin America, by opening production plants in Mexico to facilitate domestic firms’ access to the U.S. market. If that formula proves to be effective, it will likely be replicated. But while this will benefit Chinese businesses, it may also paradoxically strengthen commercial links between the U.S. and Latin America, instead of weakening U.S. influence there.

That speaks to some of the difficulties of reproducing a system of closed spheres of influence in a globalized economy with much more interconnectedness—and far more consolidated nation-states in the developing world—than existed in the 20th century. In anticipation of the next phase of globalization, companies—and governments—are likely to take advantage of multipolarity in the international system, dispersing their production into various supply chains in order to retain access to both Chinese and U.S. markets.

All of this means that, while China and the U.S. might be slipping into a “Cold War 2.0,” Latin America, and the rest of the world, might not necessarily play along.

About Miquel Vila Moreno

Miquel Vila is a consultant and analyst specializing in geoeconomics, nationalist movements and China. He is the executive director of the Catalonia Global Institute. Follow him on Twitter at @miquelvilam.