Colombia, Dispatches, Regions

Colombian Victims in Exile Fear Speaking Out

August 4, 2016 By Daniela Castro

NEW YORK – Carlos, a middle aged man from southern Colombia, arrived in New York City last June, fleeing a series of death threats against him.

“There was [a] high-ranking officer,” said Carlos, describing what happened the day he was captured by the police at the beginning of the 2000’s. “He started to treat me badly. He took out a rifle. It looked like an AK-47. He wanted me to grab it…I started to scream. What they wanted was to have my fingerprints on the rifle so they could charge me.”

Carlos said the police presented him as a paramilitary soldier. It took him several years to prove his innocence. When he finally got out of jail, he started to receive death threats and had to hide for over ten years.

In April 2015, when the last threat occurred, he realized it was the time to leave the country. Fleeing to the United States, however, didn’t put an end to the menaces.

Colombia is close to signing a peace agreement that could end more than 50 years of armed conflict. For the first time in history, the victims have a voice at the negotiating table, which has gathered in Cuba since 2012. Sixty victims of the conflict — in five groups of 12 people from various backgrounds, harmed by different actors and injured by diverse crimes — went to Havana in 2014 to contribute to the talks. In the victim’s clause, the parties agreed to address issues of truth, justice and reparations.

But for Colombians who fled the country for security reasons, the equation is more complex and violence is far from coming to an end.

According to information from a source inside the commission in charge of selecting the representatives, the delegations included only two victims in exile. Cristina Espinel, from the Human Rights Committee in Washington D.C, estimates that this representation pales in comparison to the actual number of victims living abroad.

Another exile victim is 31-year-old Maria. Like Carlos, she asked not to use her real name for fear of reprisals.

Maria came to New York in February 2015, and lives in Queens. In Colombia, she lived in an area that funnels drugs and arms in and out the country. From the age of 6, she and her family were forced to move repeatedly. They faced death threats and saw relatives killed at the hands of armed groups: the left-wing Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), right-wing United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), and more recently, criminal groups that emerged after the demobilization of the paramilitaries, known as BACRIM (a Spanish-language acronym for “criminal bands”).

Maria left the country after two men threatened her, pointing a gun at her face outside her business in a Colombian city.

Victims in exile such as Maria and Carlos can request inclusion in the Unique Victims Register (UVR). This register, in place since 2011, compiles information from the testimonies of the victims of the armed conflict. The register includes information on demographics, crimes committed, perpetrators and the status of the request. Only victims whose registration requests are accepted can receive reparations. Once a victim requests inclusion in the UVR at one of the Colombian consulates around the world, the request goes to the Victims Unit in Colombia for review, and within 60 business days the request is accepted or denied.

However, Espinel said that the victims in exile fear registering at their Colombian embassy or consulate, preferring to maintain a low profile.

“People are scared. They don’t want to talk,” she said. “People don’t want to identify themselves because they want to avoid reprisals against their family members who are in the country. People don’t want to mention names.”

Carlos said he doesn’t trust the state but has applied to the UVR on the advice of his lawyer. Maria — despite her fears — did apply to the registry last May and said she was promised monetary compensation. She doesn’t know how much or when she will receive it.

Yet, she is not willing to apply for land restitution — another way to compensate the victims — at the Consulate of Colombia in New York, because she fears retaliation against her family members. She said that it is not safe to return to her land.

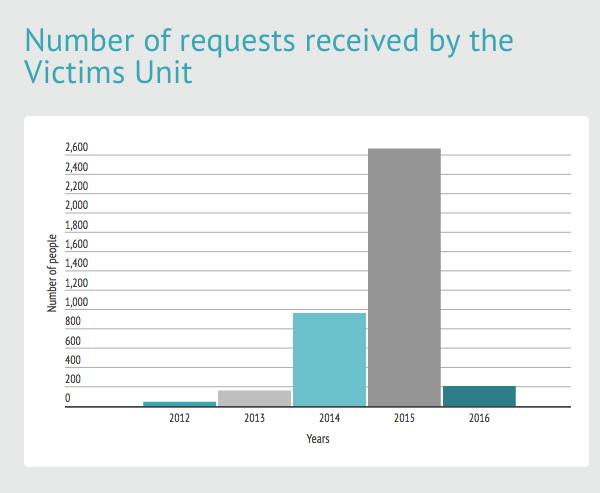

Since 2012, the Victims Unit has received 4,049 requests from victims abroad, of which 2,837 have been accepted, 675 have not and 474 are pending, according to data compiled by the unit. The highest number of requests are from Canada (822), Ecuador (806) and the United States (785). Most of those in exile fled between the late 90s and the beginning of the 2000s, when the violence in Colombia reached its peak.

Colombian Consulates around the world have been working with the Colombian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in outreach initiatives to victims to inform them about the peace process and to give them a space to communicate their fears and doubts, according to a spokesperson at the Colombian Consulate in New York City.

The chart below shows an increase in the number of requests to the Victims Unit. But because many victims are afraid or unwilling to report the crimes, it is not clear how this number compares to the total number of victims in exile.

According to a spokesperson from Colombia’s Movement of Victims against State Crime, persecuted citizens fled the country without reporting the crimes, so it is difficult to confirm the true number of victims.

In spite of the government’s outreach efforts, Colombia’s history of impunity has fueled skepticism and uncertainty among victims abroad.

In the case of Carlos, he has said that a high-ranking police officer was behind the attacks against him. The police officer was dismissed from his post for five years, but he was then reintegrated into the police force. Carlos said the high-ranking police officer is still pursuing him, and he now seeks security guarantees from the state for his family in Colombia.

The abuses committed by the Colombian state and the pervasiveness of impunity, especially among high-level public figures, have been well-documented by both national and international organizations.

“Of 1982 massacres reported, 158 — 8 percent — were committed by the security forces [from 1983 to 2013],” according to a report by Colombia’s National Historical Memory Center, a governmental body in charge of collecting data and testimonies on human rights violations in the context of the conflict. This figure does not include massacres committed in collusion with other armed actors. Additionally, the center asserts that “from the 23,000 selective killings, 2,400 were committed by members of the security forces, more than 10 percent.”

Furthermore, a 2015 Human Rights Watch report concluded:

“As of July 2014, the Human Rights Unit of the Attorney General’s Office was investigating more than 3,500 unlawful killings allegedly committed by state agents between 2002 and 2008, and had obtained convictions for 402 of them. The vast majority of the 785 army members convicted are low-ranking soldiers and non-commissioned officers. Some military personnel convicted of the crimes have enjoyed extravagant privileges in military detention centers.”

Carlos sued the state in 2013 and won the case on May 15, 2015. According to the courts, the government is required to pay Carlos an indemnity for the damages caused, which he has not received yet.

The economic compensation, however, is not the only closure that many Colombian victims seek. “No one apologized to me,” said Carlos. “Nobody repaired me psychologically, and sometimes that is more important than the money,” he said.

Carlos is a patient of the Roberto Clemente Center in New York City, where he receives psychological support after being diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Maria is also skeptical about the peace process. In spite of the negotiations, she said the violence and death threats have not stopped in her hometown.

“If a peace process is signed, I don’t plan to return [to Colombia], nor forgive,” she declared. “The peace process is a lie. I don’t believe in these people [the FARC] or the government.”

Maria and Carlos are applying for political asylum. But starting a new life isn’t simple.

“It is not easy to be here as a victim and undocumented,” said Carlos.

Maria said that she misses her home life in Colombia.

“It has been very hard,” she said about her life in New York. “I was depressed. Without my friends… my brothers and sisters… Starting here from zero has been very difficult, very very difficult.”

About Daniela Castro

Daniela is a Colombian freelance journalist currently living in New York City. She is pursuing a Master’s degree in Journalism at the City University of New York (CUNY) where she specializes in international and investigative reporting. Daniela worked for over three years at InSight Crime, a web-based think tank based in Medellin, Colombia, specialized in investigating organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. She has studied the armed conflict in Colombia as well as organized crime in Latin America, and more recently in Eastern Europe. She has covered issues related to human rights, immigration and organized crime. She has a bachelors degree in Political Science from the Universidad de Los Andes in Bogota, Colombia.