Central America, El Salvador, Photo Essays

El Salvador’s Murdered Ex-Archbishop is Canonized

October 18, 2018 By John Sevigny

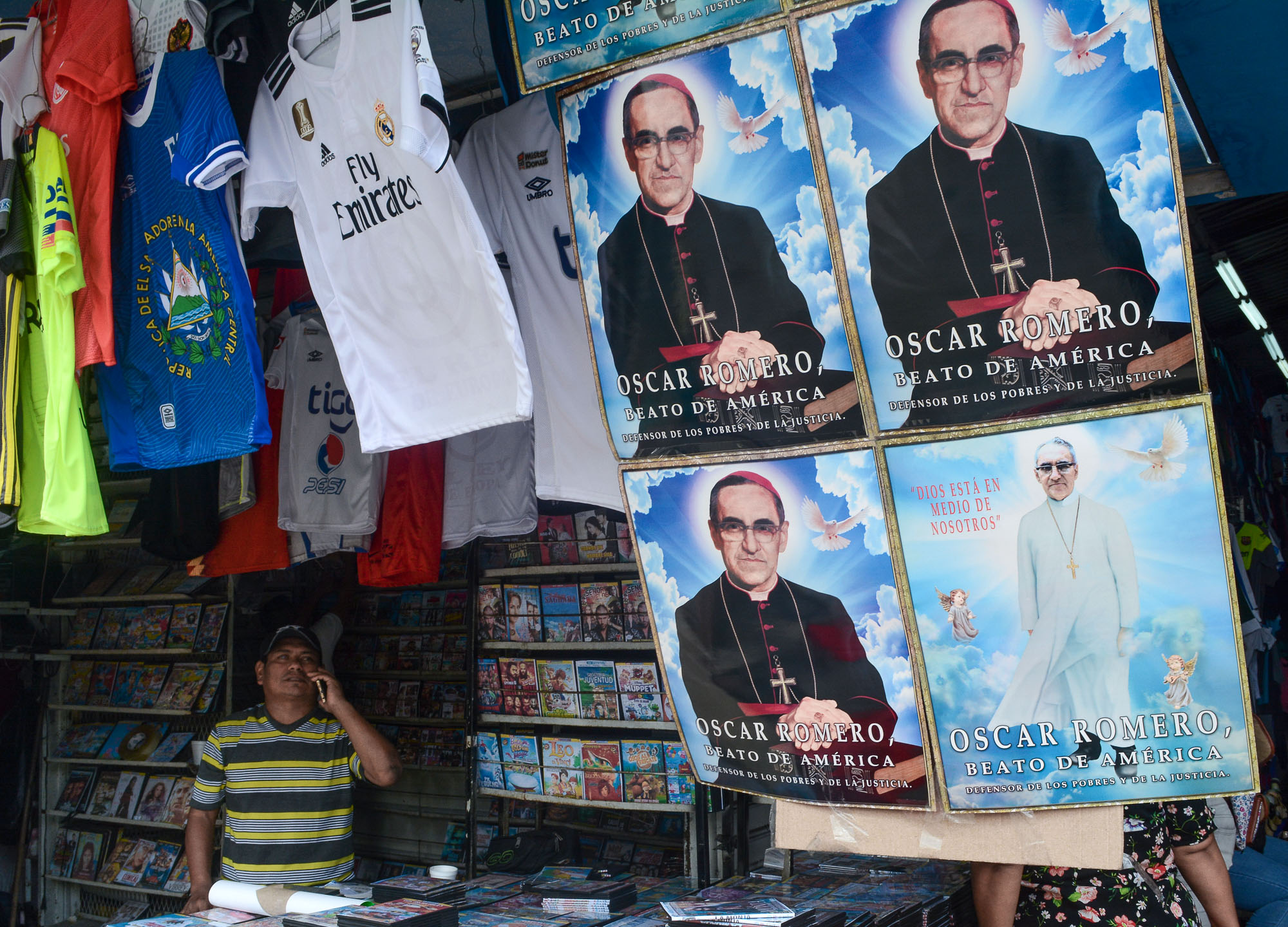

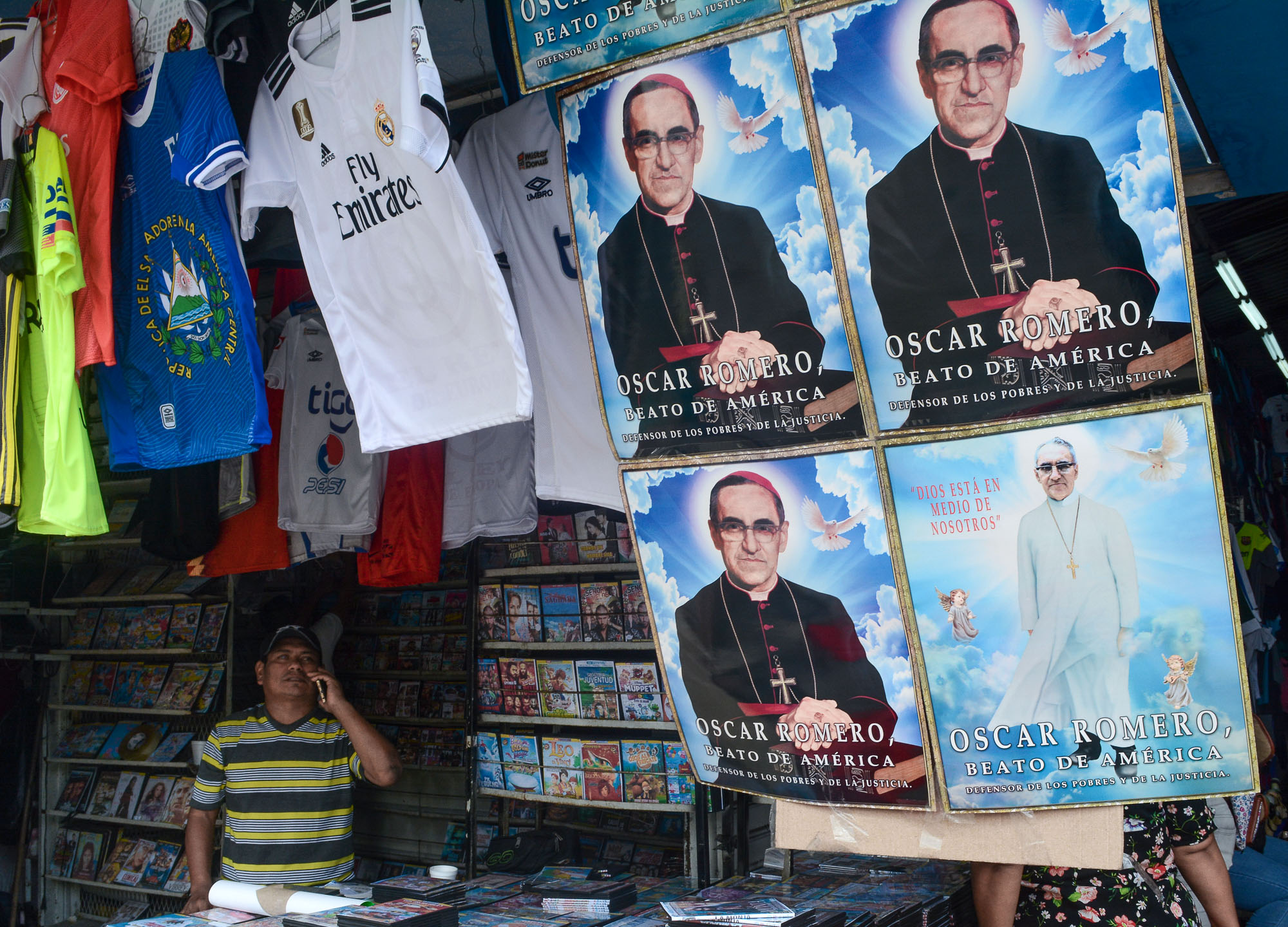

A man sells posters of Oscar Romero just moments before his canonization.

SAN SALVADOR, El Salvador – At 2 a.m. local time last Sunday, while gang-related killings continued throughout the country, El Salvador’s murdered former Archbishop Oscar Romero was canonized. It may have seemed like just a religious rite, but for El Salvador it represented more. As thousands gathered in the capital San Salvador to watch the broadcast from the Vatican and a holographic image of Romero in front of San Salvador’s cathedral, it felt like a glimpse of hope, in a country still reeling from a civil war. Church leaders said they hoped the long-awaited canonization of Monsignor Oscar Romero – killed by right-wing assassins in 1980 during mass – would bring unity and even a measure of security to a country that saw 1,300 homicides in 2017. The idea is far from unreasonable in a country plagued by crime and still recovering from an 11-year civil war in which 75,000 people died.

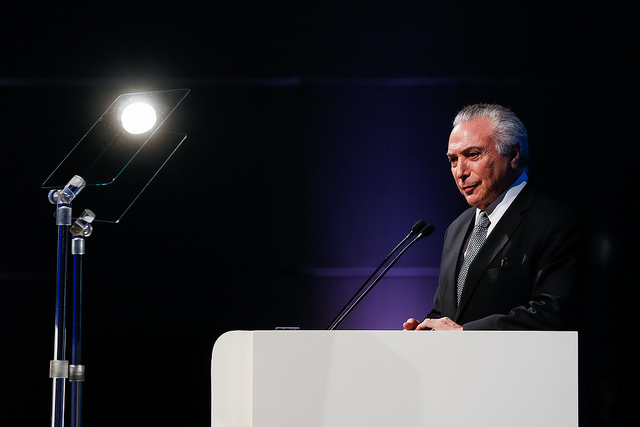

Gregorio Rosa Chavez, El Salvador’s first cardinal, talks about Oscar Romero’s life and legacy.

In an interview before leaving for the Vatican, Cardinal Gregorio Rosa Chavez, who served as Romero’s right-hand man, said he believes the now-sainted archbishop holds appeal for the young and that his canonization may bring a measure of peace to this troubled country.

“Monsignor Romero attracted young people and this could mean a positive change for the country,” Rosa Chavez said. “We see that young people are interested in knowing about Romero’s life and work.”

Some think that’s idealistic.

The celebration in San Salvador underscored the fact that this country the size of Massachusetts remains as divided and violent as ever. Moreover, it reopened conversations about Romero himself, detested by the right, embraced by the poor, and left vulnerable by the Vatican.

A boy walks past an image of Oscar Romero near the chapel where the bishop was murdered in 1980.

At a plaza fronting the cathedral, television screens showed pictures of Romero as well as local pundits discussing his legacy to a few thousand waiting to watch the canonization scheduled for 2 am local time Sunday.

Anyone expecting solemnity would have been in for a surprise.

On one screen, a holographic image of Romero walked back and forth among attendees projected behind the computer-generated Romero. There were drum circles, a magician doing tricks on a nearby side street and people dressed as popular cartoon characters mingling with the crowd. A girl handed out coupons for a local pizza parlor and a band played tropical-style music.

Visitors passed through the basement of the cathedral where Romero’s body is entombed. Vendors sold Romero T-shirts, key chains and other souvenirs.

A group of musicians crosses San Salvador’s central plaza just hours before the canonization of Bishop Oscar Romero.

Worshippers kneel to pray at the tomb of Saint Oscar Romero inside San Salvador’s cathedral.

One of hundreds of police officers providing security for the all-night celebration dismissed the idea that Romero’s message and canonization would reach the young and marginalized in this society – particularly members of Barrio 18 and Mara Salvatrucha 13 – El Salvador’s two largest gangs.

“Let me put it this way,” said the officer, who declined to offer his name because he was not authorized to speak to the media. “Between dawn and 11 a.m. we had four shootings, three of them fatal, all within two blocks of here. And we’re investigating another. This event has a beautiful message but it doesn’t penetrate the world of delinquency

Nor did it convince right-wing, government delinquents – emboldened and financed by Ronald Reagan – in the 1980s, people who coined the phrase, “Be a patriot – kill a priest,” according to Virginia Garrard-Burnett, a researcher at the University of Texas’ Department of Religious Studies.

Romero is the subject of a song by Panamanian music legend Ruben Blades, at least two movies and countless books. His image, with thick-framed glasses and a gentle face, is as well known here as that of the Virgin of Guadalupe is in Mexico. Appointed archbishop of El Salvador in 1977, he was seen as a reserved priest who would keep the church out of politics in a country in which tensions between the rich and poor were rising.

Between 1977 and 1980, 50 priests, misunderstood or maliciously characterized as communists, were threatened, attacked or murdered, Romero said in a March 1977 sermon at the funeral for his friend and colleague Father Rutilio Grande.

Photographs of guerillas, civilians and other victims of Salvadoran death squads on display during the celebration to mark Bishop Oscar Romero’s canonization.

If he ever planned to sit on the sidelines, that changed the year of his appointment when Grande was murdered by government security forces, according to the London-based Archbishop Romero Trust. Grande had embraced the cause of the poor and vulnerable long before Romero. Five more high profile priests were killed soon afterward. The others were posted at small churches in rural areas and their deaths often went unreported. Despite the violence, Romero remained focused on the rural and urban poor, people who often lived far from the capital and were most vulnerable to attacks by the military, police and other forces.

Romero rejected the idea, rooted in the bloody division of the Cold War, that the solution to El Salvador’s problems was further violence by this country’s left-wing guerillas.

“Let no one present today think that this gathering in the presence of Father Grande’s body is some political act with sociological or economic implications,” Romero said at Grande’s funeral in March 1977. “There can be no peace or love based on injustice, violence or intrigue.”

Romero, many say, was well aware that own his life would end in violence.

According to accounts by Bishop Orlando Cabrera, a retired bishop, and Romero’s own brother, the controversial priest was well aware he was going to die when he closed his penultimate homily by ordering soldiers to disobey their commanders.

A man looks at an exhibition of photographs of slain bishop Oscar Romero.

A man views a reproduction of a Diocese newspaper showing Oscar Romero’s body gunned down during mass.

“I would like to make a special appeal to the men of the army, and specifically to the ranks of the National Guard, the police and the military. Brothers, you come from our own people. You are killing your own brother peasants when any human order to kill must be subordinate to the law of God which says, “Thou shalt not kill.” No soldier is obliged to obey an order contrary to the law of God. No one has to obey an immoral law. It is high time you recovered your consciences and obeyed your consciences rather than a sinful order … In the name of God, in the name of this suffering people whose cries rise to heaven more loudly each day, I implore you, I beg you, I order you in the name of God: stop the repression.”

He was shot and killed the next day during Mass at a small hospital chapel, his blood, according to legend, dripping into communal wine on the altar.

Most Salvadorans over the age of 30 know the last sentence of the above passage by heart. Indeed, it’s one of the most passionate and direct orders given by a priest in modern times.

Many Salvadorans, including Evangelical Christians and others have recognized Romero’s sincerity. But many young people, have no memory of Romero or familiarity with the civil war or the period of violence against priests.

At San Salvador’s main plaza, a police officer stands guard in front of the National Palace adorned with quotes by Oscar Romero.

Jorge Rivera, a Honduran Garifuna who has spent a decade in El Salvador “running errands” for one of this country’s gangs, is as skeptical as the aforementioned police officer.

“This country fought a war, had a major gang crackdown, then a gang truce all to put things in order,” Rivera said as he sat with friends in a cavernous, near-abandoned bar a few blocks from the celebration. “What makes them think that elevating one man to sainthood is going to heal this country? The problem is division.”

Rivera referred to a crackdown called Super Mano Dura by former president Tony Saca now in prison on corruption charges, and a short lived truce between gangs and the government in 2012 that briefly lowered homicide rates before the government scrapped the plan.

But Dennis Balasio, an attendee of the celebration, said that whether gang members and others come around or not, the church has to work to spread Romero’s message.

“We have to make the call to everyone all the time and hope they will approach the church and Santo Romero,” Balasio said. “But the decision is in the hearts of each individual.

A framed image of Oscar Romero sits atop San Salvador’s Cathedral on the eve of his canonization.

At a market, a man sells Oscar Romero posters and other souvenirs related to the slain bishop.

A street musician crosses San Salvador’s main plaza the morning before Oscar Romero’s canonization.

About John Sevigny

John Sevigny was born into a family of Methodist Civil Rights advocates and political activists. As a photographer and writer he has worked for the Associated Press in Mexico and in the Miami office of EFE News, the official agency of the Spanish government. He has covered the drug cartel war in Northern Mexico, Central American gangs, contemporary activist movements in Guatemala, elections and issues related to religion. He has given guest lectures on his own photography, journalism, structural violence and Modernism at universities including Pratt Institute, Loyola in Chicago, Depaul University, and many others. Sevigny has had more than 50 photography exhibitions in the United States, Latin America and Europe. He currently gives photography classes at the Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas in San Salvador, El Salvador. His website is www.johnsevigny.org.