Argentina, Dispatches, Features, Southern Cone

Decades After Argentina’s Dictatorship, the Abuelas Continue Reuniting Families

March 24, 2020 By LuciaCholakian

This story was co-published with NACLA.

Due to the coronavirus, this year is the first time since 1983 that the Abuelas and Madres of Plaza de Mayo won’t march on the anniversary of the Argentina’s military dictatorship. Nonetheless, the “Día de la Memoria” will continue and thousands will demand “memory, truth and justice” from their homes. The struggle to hold the military to account for crimes against humanity are a part of Argentinian identity. A group of grandmothers leads the story of that struggle.

It was an atypical grandmother’s birthday. On February 18, Delia Giovanola, who had just turned 94, sang “Feliz Cumpleaños” surrounded by a group of people that included her comrades from Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. She clapped with excitement and, once the song was over, turned to hug her grandson Martín. Even though he is 44, it was just their fourth birthday together. Martín has only been Martín since the day he got the phone call that changed his life.

On October 16, 1976, Stella Maris Montesano, 27, and Jorge Oscar Ogando, 29, were kidnapped by the military. They were taken to the Pozo de Banfield, one of the many centers for clandestine detention that operated under the Argentine military civic dictatorship. The intention was to torture and kill the mostly young detainees in an alleged crusade against the “subversive germ.”

Argentina’s dictatorship took place in the context of systematic extermination of guerrillas and left-wing ideas in many other Latin American countries. Chile, Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay, and other countries had similar dictatorships, gathered under Plan Cóndor, a U.S.-backed campaign that united the military governments through intelligence to detect and suppress any potential opposition to their power. The activists in Argentina were mainly divided in two groups: Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo and Montoneros. After the 1976 coup d’etat, most of them went into hiding and organized in secret.

Stella Maris Montesano and Jorge Oscar Ogando.

During the first years of the military government, their political activity was suppressed and young activists went missing. After democracy was restored in 1983, investigations were opened and society began to find out about the crimes against humanity during the dictatorship. Some of them involved disappearing the bodies in “death flights,” throwing prisoners out of planes into the Río de la Plata.

Argentinian society was paralized and under a state of terror. Human rights organizations were the few who went fearlessly out on the streets to demand information about missing people, led by a group of mothers and grandmothers who were desperately looking for their children and grandchildren. The Abuelas of Plaza de Mayo association continues their search today. They developed scientific methods to identify their grandchildren, and achieved the construction of public policy to search for traces of the violence during the dictatorship.

Families like Martín’s have been reunited through their struggle. Stella Maris, his mother, was eight months pregnant when she was kidnapped. She gave birth to a boy named Martín on December 5, 1976. Shortly after, she was taken to another clandestine center. Both her and her partner Jorge remain disappeared, two of the 30,000 missing people after the genocide.

Juana Elena Arias de Franicevich, a midwife who collaborated with the dictatorship, forged Baby Martín’s birth certificate. She is known to have forged at least 10 other certificates. She died in 1995 and her crimes went unpunished.

The fate of the children born in captivity varied. Many were adopted by military families and grew up in violent and oppressive environments. Others, including Martín, were raised by families who had no clue of their origin. This is why Martín chooses to use the word “adoption” as opposed to “appropriation” when he refers to the family in which he grew up.

Martín was raised as Diego and lived a healthy and happy youth. When he was 22, he moved to Miami in search of new opportunities, where he made his career selling electronic devices. He got married and had two daughters, who were 11 and seven when he found out the truth about his identity.

Martín, unlike many of the almost 130 adults who have had their identity restored, showed up intentionally to find out if he was a nieto. Most people his age knew by heart the campaign of the Abuelas that ran on TV, radio and newspapers during their youth: “If you were born between 1976 and 1983 and have any doubts about your identity, call.”

Martín’s adoptive father was open about the fact that he was not his biological father. Martín began actively searching for his true identity after his adoptive parents died. That year, 2015, he visited the Buenos Aires office of the Abuelas. A few days later, he was already back in Miami getting the DNA test at the consulate.

“I was determined to find out the truth about my identity,” he recalls. His sample was sent to the National DNA Data Bank (BNDG), the archive of genetic material extracted from relatives of disappeared people.

Seven months later, he was at his office in Miami when his phone rang. It was Claudia Carlotto, head of the National Commission for the Right to Identity (CONADI).

“Sit down,” Claudia said to Martín. “I’ve got some news.” Claudia informed him that his DNA tests came back positive, and that he was the son of Stella Maris and Oscar.

“And you have a grandmother,” she added. “She’s been searching for you like crazy for 39 years.”

Finding Martín

Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo are now a worldwide symbol, but their struggle went unrecognized for many years. Delia was one of the 12 founders of the organization and searched relentlessly for over 500 missing babies born in captivity. She still does, as 400 remain missing. Martín was the grandchild number 118 that the Abuelas found with support from the CONADI and the National Bank of Genetic Data.

When she found out about Martín, Delia was in a car heading to a conference about the search for the missing grandchildren. She received a phone call from Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo asking her to come to a meeting. She refused; Delia never misses commitments. Back at the office, they asked the organizers of the conference to tell Delia it was cancelled. After they did, Delia agreed to go to the Abuelas office, with no clue of the news she was about to receive.

The three words that she’d been waiting for came from the president of the Abuelas, Estela de Carlotto:

“We found Martín.”

Delia broke into what she describes as a mix of laughter, tears, and shrieks. Her joy grew when Claudia added that he wanted to talk to her on the phone. This was a first: Grandchildren usually take their time before contacting their families of origin. Martín was enthusiastic about hearing the voice of the woman who had searched for him for almost 40 years.

“Hola, Martín! Martín!”

“Hola…You are calling me Martín, but my name is Diego…”

Martín was hesitant. He was sitting down, and the surroundings in his office stood still while his life transformed with each passing second. Delia told him that she had searched for him under the name of Martín—that it was the name that his mother had chosen for him. And again, he absorbed the new information. He accepted being called Martín.

Delia told him she was very modern and used social media and Whatsapp daily, so they could connect easily. The subsequent calls were through Skype, the platform in which they “met” officially. He travelled to Argentina a few weeks later, in December. He visited with his now ex-wife and two daughters.

“I had told my grandma I would visit after lunch,” Martín says. “But we arrived a bit later. That’s what she told me when she saw me: that I was late!”

Martín and Delia.

A New Start

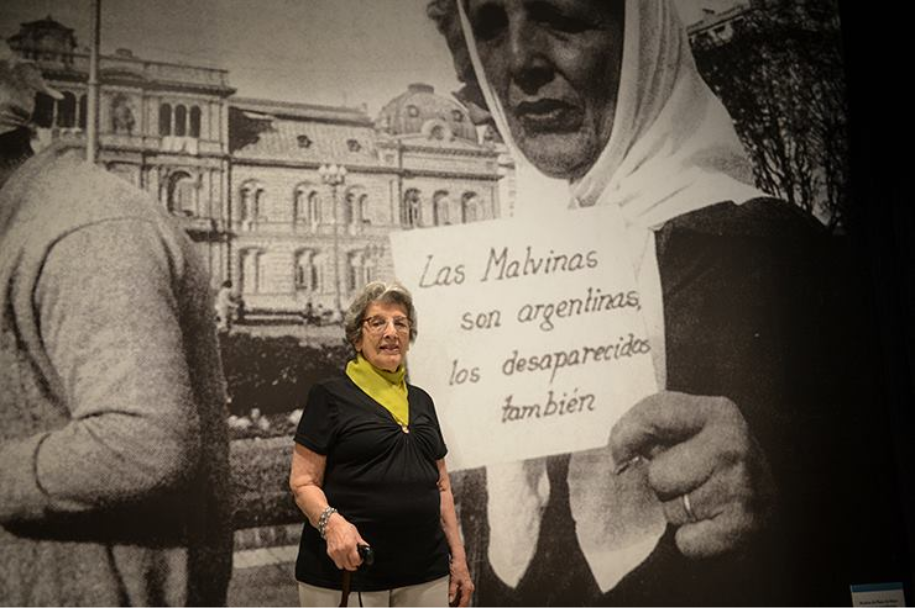

Delia has a reputation for fearlessness. During the beginning of the Falklands War in 1982 that Delia seized on the presence of international media in the country, and held a sign in front of the news cameras that read, “Malvinas are Argentinian, the disappeared too.” The courage of the Abuelas was a threat to the military government, and many of them were kidnapped and disappeared. Nothing stopped them.

She was grandmother to a girl, too. Virginia was Martín’s older sister. When Jorge Oscar and Stella Maris were kidnapped, Delia took her in and raised her. Virginia joined the struggle of the Abuelas to find the truth about what had happened to her parents and to find her little brother. But the pain was unbearable and Virginia died by suicide in 2011. Delia recalls this as one of the hardest moments of her life.

Now, Martín shares her family history. He says, “This is what came with my search: my history. It’s a very hard truth.” Still, he is happy he found it. After finding out about his true identity, Martín started traveling back to Buenos Aires every month.

“Having been in the US for a long time, I felt uprooted from Buenos Aires for the first time after 2015,” he remembers. His work allows him to spend time both in Buenos Aires and Miami, where his daughters still live.

Being part of the Latinx diaspora in Florida, Martín faced a double challenge: He had to adapt to his new identity in a different country that did not share the consciousness of what it means to be a grandson to Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. Luckily, Martín is mainly surrounded by Latinx friends and colleagues, making it easier to share his story. Before the DNA result, he had barely spoken about the fact that he knew he was adopted. Only his ex-wife knew about his doubts. Now, in spite of keeping Diego as his legal name in the US, he is open about his story.

The life of the grandchildren change swiftly when their identities are restored. Many re-do their lives completely, change careers, separate from lifelong partners, and move to different cities. One thing that Martín shares with many of the 128 restored grandchildren is the commitment to their new families and particularly to the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. With the aging of the Abuelas, the grandchildren know they will be the ones to carry out the project in the future. And the search will grow even more complex. The grandmothers started looking for children, then for young men and women. Now, they are searching for mature adults and even great-grandchildren.

Martín is aware of the privilege he had by being able to connect with his grandmother and finding her healthy enough to share adventures. Delia was revitalized when she found him. Each time he visits, she makes plans for both of them, takes him to different conferences, and expects him to spend time with her in her house in Villa Ballester, in the northern suburbs of Buenos Aires. He has his own room: She moved into a smaller bedroom so that he could be comfortable. In spite of being part of a league of exceptional and now world-famous grandmothers, Delia is a typical granny. She even resists cursing in front of him.

Every Día de la Memoria gathers hundreds of thousands marching across the country under the slogan “memory, truth and justice.” These three words have not only defined the generation of young people that lived under terror during those years but have also constituted a social identity that shapes today’s youth.

After singing happy birthday, after Delia hugged Martín for several minutes—something she had been dreaming about for 39 years—Estela de Carlotto invited some school students who were visiting the Association for the first time to share cake and wish Delia a happy birthday. As she let them in, she warned them:

“You are now in the house of Las Abuelas, where there is no sorrow. Only lucha.”

And the Abuelas will never lose their perseverance: The struggle will go on for all of them until all of their grandchildren are reunited with their families.

Lucía Cholakian Herrera is a freelance journalist based in Buenos Aires. She reports human rights stories, feminist struggles and investigates identity in contemporary Latin America. She has won a Premio TEA for her coverage on sexual assault trials in Buenos Aires.