Dispatches, Features, Paraguay, Southern Cone

Survivors Recount Sexual Violence During Paraguay Dictatorship

June 12, 2020 By LuciaCholakian

This story was originally published by VICE en Español, and is translated to English for the first time on Latin Dispatch.

Trigger warning: This article includes references to sexual violence and child sexual abuse.

BUENOS AIRES—Coronel Pedro Julián Miers, commander of the Presidential Guard Regiment in Nueva Italia, Paraguay always called Julia Ozorio Gamecho “Pulgita,” or the Little Flea. He used this nickname for two years while he held her captive in the Laurelty estate. During the dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay, from 1954 to 1989, Laurelty was one of five sites where girls and women were sexually exploited, enslaved, and tortured.

Julia was 12 on February 4, 1968, when Coronel Miers kidnapped her and took her to Laurelty. According to her testimony and that of several others, Miers kept girls enslaved for military officials. Her captivity lasted until March 10, 1970. Today, speaking from her home in Buenos Aires, where she has lived for more than 40 years, she emphasizes one thing: “They keep pursuing me.”

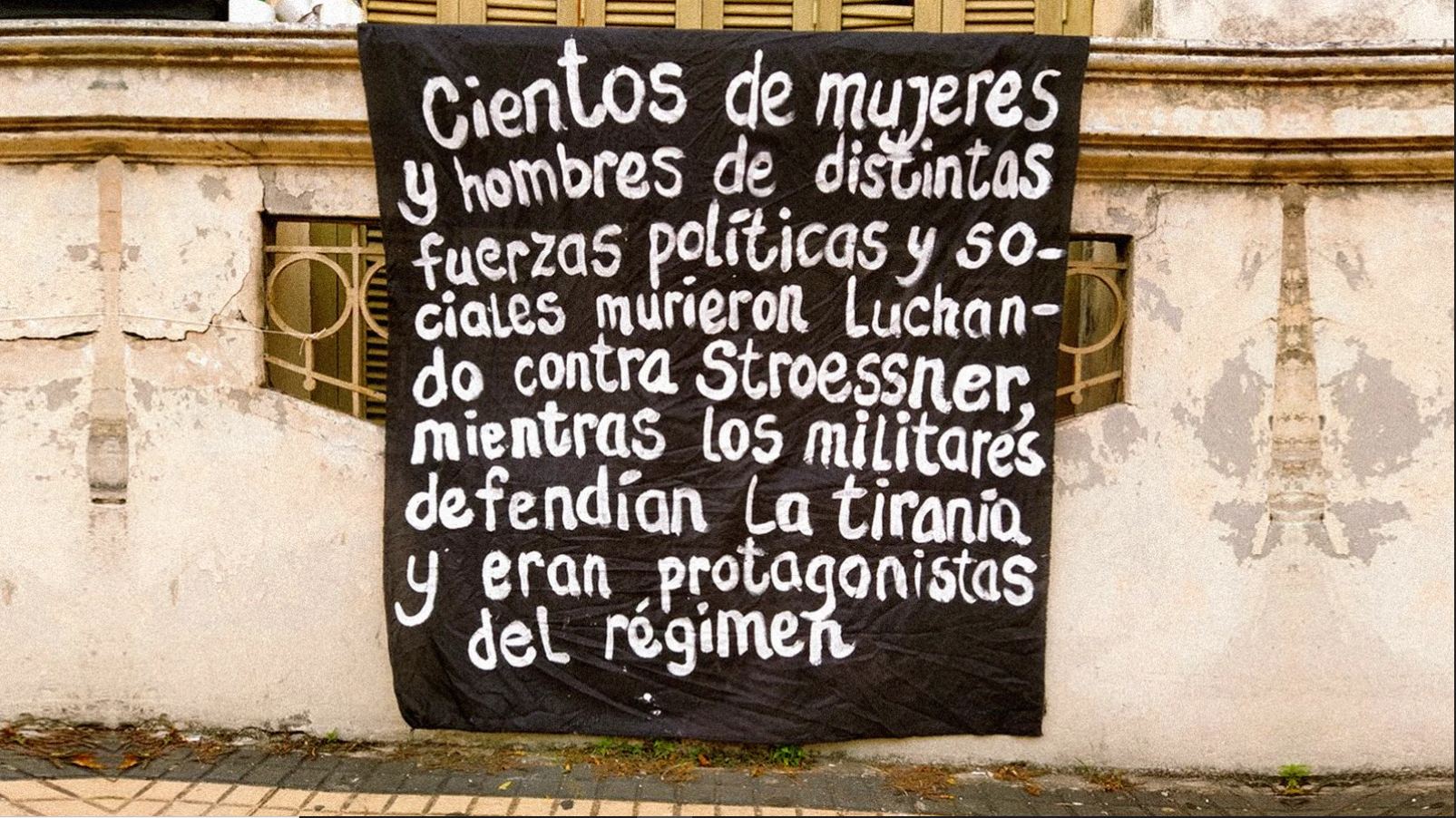

Unlike many other countries of the Southern Cone, Paraguay did not have a process of historical memory and reconciliation after the end of the dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner. This goes beyond juridical processes to address the profound, cultural impacts of dictatorship. Paraguay abandoned the possibility of constructing social memory, allowing the sexual and racist crimes committed by members of the regime to be forgotten. Many members of the military dictatorship died without punishment, some of them remembered as heroes. The dictatorship was especially brutal against the Guaraní people and campesino organizations, who conformed the Agrarian League, one of the strongest resistance groups to the regime. The crimes that Stroessner and his henchmen committed at the estates in Asunción must be viewed as state-sanctioned misogyny and racism.

Julia Ozorio Gamecho, like many of the girls, was kidnapped near her home in Nueva Italia, a city close to the capital. “We arrived and there were soldiers and civilians guarding the place,” she says. “When I got there, I threatened to escape. But [Miers] stopped me and said in his military voice, ‘Stop, Pulgita. There is no exit here. So, don’t even try to escape.’”

Forty years after her kidnapping, in 2008, Julia published a book called “Una rosa y mil soldados.” The book relates her life history. Even though Julia gave testimony to the Human Rights Prosecutor’s Office in 2008, Miers died in impunity. The book was a way to share her testimony with whomever wanted to listen. She wrote that Miers visited the estate about twice a month. The rest of the time officers of lower ranks lived at the house. She saw many other girls pass through. She said that most of the Indigenous girls who were kidnapped were later killed. Julia’s testimony is one of the few that informs our understanding of the system of sexual violence that operated under the Stroessner government.

One night in 1975, Malena Ashwell, member of a well-known diplomatic family, was having dinner with her husband, a naval officer, at the house of one of his superiors. Neighbors called them over to their house, where they had found the bodies of three girls, between eight and nine years old, on a pile of sand. They had signs of sexual abuse. Ashwell’s life changed that day: she began to try and call attention to the situation any way she could, including telling the story to The Washington Post using a pseudonym. But the regime persecuted her, eventually throwing her in prison. While detained, she was tortured and attempted suicide. Finally, her father was able to arrange her release on the condition that she would go to the United States and not return to Paraguay.

What Ashwell witnessed took place at a house in the Sajonia neighborhood of Asunción, where Coronel Perrier kept girls he bought from poor, campesino families. The testimony of one anonymous victim, in the “Calle de Silencio” documentary (2017), revealed more details about the house. The girl was sold when she was 13, for 31,000 guaraníes (less than 5 USD) by her mother. A woman took her to the home of Colonel Perrier, who greeted her, and they talked for three hours. Then she was lead to a bedroom. The sexual slavery continued. Every so often they would allow her to go to her family for a night, and then would come looking for her the next day. “I lived waiting for them to capture me,” she says in the documentary. “And there I met the president.”

Stroessner visited the residence in Sajonia. Other girls were known to be held captive in a house in Ití Enramada, a neighborhood in the south of Asunción. “The president would visit and would drink tereré [a type of yerba mate], and sometimes he would have lunch,” the victim remembers. Neighbors would see him arrive at night once or twice a week, driving his own car, and parking at the house.

Many girls died at the Sajonia house and their burial sites are unknown. The identity of the three girls who Malena Ashwell saw was never confirmed, nor their final resting place.

Feminist sociologist Kathleen Barry warned in her 1979 book Female Sexual Slavery that the Stroessner government facilitated sexual exploitation of campesino girls domestically and as part of international trafficking networks. “The enslavement of girls and women in Paraguay can be traced to the corrupt military dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner,” Barry wrote. “Before his coup, there was only one brothel in all of Asunción.”

The consequences of naturalizing sexual exploitation persist to this day. According to the General Department of Statistics and Censuses, almost 50,000 girls and boys in Paraguay live in conditions of “criadazgo,” in which parents give their children to families of a higher economic status who, in exchange for education and food, make them do domestic labor. These children’s confinement often leads to physical and sexual abuse. The stories of youth abused in the criadazgo system are not so different from the stories of the girls held captive during the Stroessner regime.

Julia Ozorio says that the genealogy of what she lived through and what children live through today is the same. “It is with that mentality that the dictatorship controlled the people in the countryside and elsewhere. It shouldn’t be like this, but it is. The violence that I suffered and the violence against the criadazgo is racist. And the country continues to be racist.”

While in Argentina the objective of the dictatorship was to eliminate leftist and Peronist political organizations, in Paraguay, the regime targeted the Guaraní and Indigenous culture more generally. According to the Commission for Truth and Justice, acts of sexual violence targeting girls usually took place during military and police operations in campesino communities. 37% of girl in the Commission’s survey reported suffering these abuses, of which 85.2% took place in departments in the country’s interior, with majority Guaraní populations.

During her captivity Julia remembers that a German doctor appeared, who studied several of the girls’ bodies. “It was Mengele. Now I know,” she says, referring to the Nazi doctor who spent time in South America. “When a girl in fifth grade is alert, intelligent, knew how to write, he realized it. I wrote, I wrote poems and short things in the sand. And he said: this girl is going to be smart. He injected me, gave me vaccines, to fatten me up and later sell me.”

There is not specific proof that Josef Megele, the Nazi doctor who is attributed with coming up with the gas chambers, visited the houses. But there are studies showing that the regime received him in Paraguay for a period of time between the fall of Perón in Argentina in 1955, and his death in Brazil in 1979. Megele is known to have been obsessed with the bodies of girls and young people with certain physical characteristics. In his experiments on humans, he killed hundreds of people, in addition to the crimes he committed during the Nazi regime.

Julia Ozorio Gamecho’s story opened the door for more documentation of how the violence of the dictatorship persists in different forms today. Few women chose to speak up publicly about their experiences. But Julia is persistent, and she maintains a network with the women who have shared their stories with her.

“Many girls were sold during my time,” she says. “I remember names. Many of them have written to me, including from other countries where they were sold off. I have told them, ‘I will be your witness.’ I named them in my testimony. Even though nothing has come of it.”

Despite the torture that Julia suffered as a young girl, and the violence that was never recognized by her country people, on the other end of the phone she sounds animated when asked about her story. She repeats that she wants is for all of it to be known. In Argentina she learned that talking is the best antidote against forgetting.

“I spoke out because I wanted to help all the women who were like me,” she says. “We cannot continue holding this story without talking about it. Every story written with blood must be told, so it does not happen again. We have to let go of the monster inside us. Why continue crying? We didn’t invent our stories. We were just girls.”