Features, Mexico

Children of Mexico’s Disappeared Seek Justice

March 30, 2010 By Mari Hayman

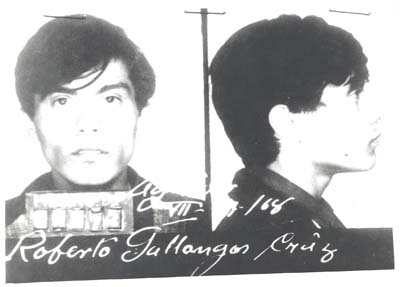

Aleida's father, Roberto Gallangos, was detained on July 26, 1968. This photo was taken by Mexico's Federal Security Directorate (DFS).

NEW YORK — Aleida Gallangos is not easily deterred. Over five years ago, when she realized that the only way to find her long-lost brother in the United States was to comb through all the entries for “Juan Carlos Hernández” in a phone book, she made the calls. When her brother’s adoptive family thwarted Aleida’s first attempts to contact him, she got on a plane from Ciudad Juárez, Mexico and flew to Washington D.C. to look for him herself. And when Juan Carlos finally called Aleida to determine whether she was really his sister, she spent days on the phone with him as he struggled to come to terms with the truth.

“Do you want us to see each other?” Aleida asked. “I promise I don’t want to hurt you.” The siblings finally reunited in the winter of 2004 after 29 years of separation, and shortly thereafter, Aleida moved to Washington D.C. to be near Juan Carlos.

Five years after finding her brother, Aleida, now 37, is not done fighting. Her new mission: to bring the Mexican government to trial for the clandestine war that disappeared over 1,000 people, including her parents, her uncle and their two friends, 35 years ago. On March 8 of this year, Aleida filed a petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) against Mexico for failing to investigate human rights abuses carried out in the country during the 1970s and 1980s. The petition contends that the Mexican government is not only responsible for mass kidnappings, torture, and disappearances during the country’s “dirty war,” but also for its failure to address the mounting evidence of these crimes in a court.

“I am demanding that the government apologize to all the families for our pride and dignity and above all, because these things keep happening,” Aleida said. “There are still arbitrary detentions even now with Calderón.”

Aleida’s own parents were political militants in the Red Brigade of the September 23 Communist League, and witnessed the violence of the 1968 student protests preceding the massacre at Tlatelolco Plaza that killed hundreds of Mexicans. Documents obtained from Mexico’s National Archive show that from as early as 1968, Aleida’s father was under surveillance for suspected “terrorist” activity. In June 1975, security forces raided the Mexico City house where Aleida, then only two years old, was living with her parents, her three-year old brother Lucio Antonio and other members of the September 23 Communist League, and took Lucio Antonio away. In the following weeks, Aleida’s parents were kidnapped – her father Roberto Antonio, 25, and her mother Carmen, 23, were never seen again.

Alone and suddenly orphaned, Aleida was rescued by Francisco Gorostiola, a young friend of her parents who left her in the care of his family before he, too, was kidnapped and disappeared along with his companion Emma Cabrera, six months pregnant at the time of her detention. The Gorostiola family raised Aleida as their own daughter and renamed her Luz Elba. Aleida grew up unaware of her real name and with no memory of the violent destruction of her family. Lucio Antonio, abandoned in an orphanage after the police raid, was adopted in 1976 by a couple who renamed him Juan Carlos Hernández and raised him as their own. Neither of the children were told they were adopted until much later in life: Aleida at sixteen, and Juan Carlos only after Aleida came looking for him.

Unlike his sister, Juan Carlos chose to retain the name his adopted parents gave him.

“I grew up like any child in Mexico, with problems, with happiness, with the same problems as any kid in Mexico,” he said. “I was not rich, my family was not rich. We were poor. My parents tried to give me what they could, they fed me, they sheltered me. I don’t feel I regret growing up with them, I still don’t feel like a victim.”

Juan Carlos, 39, supports his sister’s petition before the IACHR but also wonders whether justice is something the commission can actually achieve. “It’s not a win or lose case because even if we go to court and win, I think, ‘what are we going to win?’” he said. “Sometimes I think about how I can be face to face with the people who kidnapped my parents and the people who took me away from them.”

“Sometimes when I’m by myself I think about it. I wonder if [my parents] are still alive, or worry about their lives or if they went to another place to hide,” added Juan Carlos. “Sometimes I think about where their bodies could be and what happened to them. You have to have this happen to you to know how it feels.”

***

Thirty-five years after they were taken from their family, Aleida Gallangos and Juan Carlos Hernández still represent the only two cases in which Mexican desaparecidos have been successfully recuperated. Juan Carlos’ “discovery” in 2004 was presented as a victory not only for his sister but for FEMOSPP (the Special Prosecutor for Social and Political Movements of the Past), the office former Mexican President Vicente Fox created in 2001 to investigate disappearances by the Mexican government.

Invited to join FEMOSPP’s Citizen’s Committee in July 2002, Aleida soon left the committee in disgust. According to Aleida, Special Prosecutor Ignacio Carrillo Prieto failed to pursue the leads she and her family gave him, and it wasn’t until Aleida tracked down her brother’s files herself at an orphanage called Casa Cuna de Tlalpan that any progress was made on Juan Carlos’ case. In declassified documents, the U.S. embassy cited an independent study that called Carillo’s office “overly focused on administrative tasks” and “unresponsive” to victims’ needs.

José Enrique González, a lawyer from the Foro Permanente por la Comisión de la Verdad who helped Aleida write her IACHR petition, agreed that FEMOSPP failed to achieve its goals. “The work of FEMOSPP was a fiasco,” he said. “They only took a few cases to court and furthermore, the cases were poorly-supported because they didn’t use the judicial standards of international law and didn’t touch the Mexican army.”

González has presented numerous petitions to the courts on behalf of the families of Mexico’s disappeared, and he admits that the process is long and difficult. “The most serious problem we confront when we deal with these types of issues is proof,” he said. “Normally, repressive acts are conducted in obscurity and rely on the protection of the State apparatus. Witnesses don’t want to speak because they’re afraid, and documents can easily disappear or get crossed out or erased.” González added, “The real difficulty is always in establishing proof, because those in power can easily erase their tracks.”

And yet, in the Gallangos Vargas case, official documents are clear which Mexican government agencies and individuals were responsible for the disappearance of Aleida and Juan Carlos’ parents: members of Mexico’s Federal Security Directorate (DFS) and the Interior Ministry. The Washington D.C.-based National Security Archive obtained pages of documents related to the case by submitting Freedom of Information Law requests to the U.S. Embassy in Mexico, the FBI, and the Mexican National Archive.

According to Kate Doyle, Senior Analyst at the National Security Archive, the organization is just starting to analyze approximately “four inches of documents” related to the Gallangos Vargas case, some of which Aleida cited in her petition to the IACHR.

“Normally in human rights cases in the past, you go to the Inter-American Commission or a court in your country with testimonies and eyewitness accounts and that’s it,” said Doyle. “And now, for the first time, we can take internal secret documents that were written by agents inside these intelligence and police institutions, signed in many cases by the chief, the director of the DFS, that clearly indicate in an irrefutable way that one; these people were under surveillance for five, six, seven years, and two; agents of the Mexican government state the dates of their internal capture and these match the date of their disappearance.”

“This is just a completely different kettle of fish,” Doyle said in reference to the abundant evidence supporting Aleida’s case. “This is a criminal case; now you’re talking. The sad thing for me is that she has to present it at the [Inter-American] Commission. This should be at the court of law in Mexico.”

***

Although there is little chance that the individuals responsible for her parents’ kidnapping will be actually prosecuted through the Inter-American system, Aleida is adamant that her petition before the IACHR will produce important results. “Some of [the perpetrators] are already dead, if not the majority. But I still think that we have to go forward with the case,” she said. “These cases make it possible to regulate the laws so that the same repressive techniques can’t be used again.”

Aleida admitted that there is a lot she hopes to learn while her petition is being considered. “Right now, there’s nothing, I don’t know where they have all that information, there’s nowhere that relatives can go to ask about these cases.”

If Aleida’s experience is any indication, the relatives of Mexico’s disappeared have few if any resources available within the country to pursue their cases. After FEMOSPP was dissolved in 2006, the office of Mexico’s General Prosecutor (PGR) presumably assumed FEMOSPP’s investigatory responsibilities. But no cases have been brought by the PGR on behalf of the disappeared since then. PGR spokeswoman Liliana Macias said that FEMOSPP had been absorbed by the PGR, but was unfamiliar with Aleida’s case. “These people have full possession of their rights,” Macias said, referring to Aleida and her family, “and one of the things those in full possession of their rights need to do is write a letter to the PGR asking for information about the missing people, and the General Prosecutor will direct them according to the information and the case. That is the resource that they have.”

Asked what had happened to the cases that had already been investigated by FEMOSPP, Macias responded, “I don’t have any information about specific cases; the General Prosecutor has that information. If they petitioned [FEMOSPP], the previous findings are sealed, and only direct victims can seek that information.”

Doyle of the National Security Archive says the PGR’s bureaucracy makes it easier to keep cases like Aleida’s a secret from the general public. “The PGR says ‘no, these are ongoing cases,’ but no, there’s a lot of lies and nonsense,” she said. “Until what point do you call this an ongoing prosecution if nothing has been done, no evidence has been moved, and this has been going on since 2003? The Mexican state will claim there is an open case here, but you can only claim that for so long.”

***

Meanwhile, Aleida and Juan Carlos hope to raise the public’s awareness of Mexico’s “dirty war” and its long-lasting consequences. “You know the stories of Chile, Argentina, Guatemala, Nicaragua,” Juan Carlos said. “You know different stories about military governments that have killed and disappeared people. Did you know about this story in Mexico before this? The government is ashamed of this story. They try to hide this story.”

“I think our story must be told,” Aleida said. “We’re just one family among so many families in this situation. There are so many families that don’t have the opportunity to bring a case before a commission.”

Juan Carlos said that he has always considered himself apolitical, but the example of his parents inspires him. “My parents had an idea of justice and they wanted to help people,” he said. “They wanted to change their lives, the social conditions, they wanted to help, they wanted to make change, and that’s very powerful for me.

“Now we know they disappeared people, they killed people for their political ideas, so that’s one of the good things that I think that has come out to the public,” Juan Carlos said. “You can say, ‘one person, okay, maybe she’s crazy’; ‘two people, okay, maybe it’s a conspiracy.’ But when hundreds of people speak, you cannot deny it.”

Images courtesy of the National Security Archive and used with Aleida Gallangos’ permission.