Central America, Dispatches, North America, United States

A Day on a New York City “Rocket Docket”

October 8, 2014 By Nicki Fleischner

The minors and their guardians sit in the fluorescent-lit room and stare at the sketch on the whiteboard. The image represents a map of Mexico and the U.S. separated by a line: the border. Elvis Garcia Callejas, a case manager with Catholic Charities, presides over the information session.

“So, you all crossed that line and that’s why you’re sitting here, right?” Callejas asks the group. A few sheepishly smile while others are busy texting on their phones.

A native of Honduras, Callejas was an undocumented minor himself before gaining citizenship. He understands the trauma many of the people in front of him experienced as well as the legal options available. In his rapid-fire Spanish presentation peppered with plenty of jokes, Callejas aims to provide the minors with necessary information while also putting them at ease before their impending deportation hearings.

At one point Callejas likens immigration officers to iguanas because of their green uniforms. At another, he explains how the inside of a courtroom looks like a church and is “just as boring.” By the end of the session minors and their guardians are chuckling along. Not only does Callejas speak the vernacular, but he is well rehearsed: he holds an identical session weekly at 26 Federal Plaza — the building that houses New York City’s immigration court — just one hour before minors are to appear before a judge.

Catholic Charities is just one of the organizations in New York City that has taken advantage of so-called “rocket docket” days, in which judges hold initial hearings for many minors simultaneously, on multiple days each week. The expedited court process is just one of President Barack Obama’s strategies to handle the surge of unaccompanied minors in the country and the subsequent backlog of immigration cases.

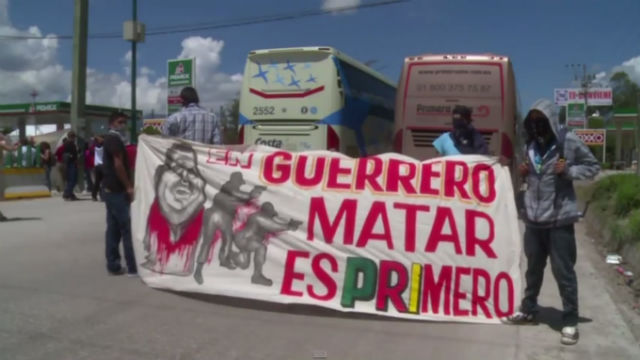

Between October 2013 and July 2014, an estimated 63,000 children crossed the U.S. border from Mexico. The majority of the children come alone from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, three countries plagued by violence and extreme poverty. The primary reasons for the surge of minors are safety concerns in native countries, misinformation regarding the leniency of U.S. immigration policy and desires to reunite with family already here.

Salvador Rodriguez, a 15-year-old from El Salvador, now lives with his 20-year-old cousin in Long Island. He left his home on a crowded bus over two months ago, leaving his parents and three siblings behind, and was detained in Texas, Arizona and New York before being released to his cousin in late August. On Sept. 26 he appears in court for the first time, along with 30 other minors.

“I have no idea what is going to happen,” Rodriguez says in Spanish after Callejas’ presentation. “I don’t speak any English, but apparently there is a translator for the judge.”

Rodriguez recognizes two boys from his journey to the border, both from El Salvador, during the presentation. The three exchange handshakes and stories in the minutes before entering the courtroom. Other minors sit silently with their guardians fidgeting with backpack zippers or listening to music from their cellphones. Nearly all of them have overstuffed envelopes in their laps containing the letter with their court date and other official forms.

Catholic Charity representatives shuffle in and out of the room, at times pulling certain families out for free legal consultations. Those not selected look on in confusion.

“Is the trial starting?” one whispers to another in Spanish.

“I have no idea.”

After about 30 minutes of anxious anticipation, Margaret Martin, Catholic Charities’ supervising attorney, announces it is time for the first group to take the elevator upstairs to the courtroom. The minors will see the judge 12 at a time, and Martin will act as a “friend of the court” during their hearings.

Once in the courtroom, minors take the stand one by one while the others merely observe, straining to hear what the judge says in preparation for their own turn. Charity representatives and a group of Columbia Law School students observe the proceedings, entering and exiting the courtroom regardless of whether someone is on the stand or not. Minors in the audience whisper to their guardians. The atmosphere is casual, the judge seemingly unperturbed by the room’s noises compounded by sounds of cellphone chatter and a television program somewhere down the hall.

Each case takes only two minutes. The judge asks for the minors’ names, the name of their guardian and their relationship to them, their native language and whether they have already enrolled in school. A translator murmurs the judge’s questions to the minors in Spanish, and most respond with short sentences. Although the judge begins each hearing with a statement declaring that these are proceedings to determine whether the minor will live in the United States, nothing near a resolution is established. Each of the 30 cases heard by Judge Virna Wright on this day merely results in the issuance of another court date on Dec. 1. In the meantime, minors hope to start school and seek help where they can find it.

“I tried to enroll him in school, but he tested positive for TB,” Rodriguez’s guardian and cousin explains. “Now he has to get a chest X-ray, but he still doesn’t have insurance, so I’m paying for it myself.”

Rodriguez’s cousin feels that getting him started at school is an important step, and one judges look upon favorably down the road. She is relieved at the speed of the first hearing, but worries it will become more involved and complicated later on.

“I was so nervous, like, what are they going to ask him? But they didn’t really make him speak at all,” she says. “It was great, now we have time to get him adjusted to Long Island.”

The children and their guardians trickle out of the courtroom as they leave the stand, their futures just as unsure as when they arrived. For now, legal limbo will be the fate of the hundreds of unaccompanied minors flooding 26 Federal Plaza in the months to come.

Image: Youtube

About Nicki Fleischner

Nicki is a Henry MacCracken Fellow at New York University, where she is earning a masters degree in Global Journalism and Latin American Studies. She is from New York City but has lived and traveled throughout the Caribbean, where she studied, wrote and worked as an English and Spanish teacher. She is particularly interested in contemporary culture in Havana, Cuba. Nicki earned her bachelor’s degree in International Literary and Visual Studies at Tufts University.

1 Comment

[…] Read the full story in Latin America News Dispatch. […]

Comments are closed.