Andes, Colombia, Dispatches

In Colombia, There Will Be Peace

September 24, 2015 By Leonardo Goi

BOGOTÁ, Colombia — September 23 marked a historical day for the ongoing peace process between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC. After an hour-long private meeting in Havana, Cuba, President Juan Manuel Santos and FARC commander Timoleón Jiménez, alias Timochenko, publicly announced that a peace treaty between the two sides will be signed in six months, and that FARC will begin abandoning their weapons only two months later. More than 50 years after the start of what has now become the longest-running conflict the western hemisphere, Colombia may finally be looking forward to the end of an armed struggle that has claimed over 300,000 lives.

Santos and Timochenko also stated that the two sides’ delegations have finally reached an agreement over the fifth item in the peace talks’ agenda, which deals with the judicial framework through which those responsible for the conflict’s atrocities will be judged. The announcement marks a crucial moment in the negotiations’ trajectory; it has been a year and half since the two delegations came to an agreement on one of the agenda’s six points. The fifth point, related to transitional justice, was seen as arguably the most problematic.

Sitting on either side of Cuban President Raúl Castro, Santos and Timochenko announced the establishment of a special tribunal to judge those culpable for the violence associated with the armed struggle. This, to an extent, does not come as a surprise: the current judicial system needed some adjustment to account for the challenges of the post-conflict stage, and there had already been talk of a new special judicial unit. What is most surprising is the way this tribunal will be managed, and who will take part in it.

One of the most problematic questions that today’s meeting was meant to address was who exactly would be judging the conflict’s culprits. The FARC had historically opposed the idea of submitting to the Colombian judiciary, as they rejected the legitimacy of the Colombian state, which they accused of being equally responsible for the conflict’s massacres.

Unexpectedly, the FARC agreed to allow the special tribunal to be composed primarily of Colombian judges, with some recognized international legal experts. Equally surprising are the forms of punishment that the agreement will supposedly entail.

On the eve of today’s meeting, many had argued that the FARC would have never agreed to a peace treaty that could have paved the way to their imprisonment. The negotiations between Santos’ government and the rebels were never conceived of as a trial against the latter, but a peace treaty wherein both sides mutually respected each other’s positions as warring parties and sought to come to an agreement of some sort. The FARC spokesperson in Cuba, Iván Márquez, had said repeatedly that members of the guerrilla group would not see a day in prison; and the chief-representative of Santos’ delegation, Humberto de la Calle, echoed his thoughts in a subsequent interview.

Not only have the FARC agreed to a tribunal headed by representatives of the state they had historically antagonised, they also agreed to forms of punishment that may entail prison terms for those found guilty. The new legal framework shall involve two fundamentally distinct routes: one for those who acknowledge responsibility for the crimes committed, and another for those who do not accept responsibility, or do so belatedly. Those who immediately confess their crimes will face confinement — though not jail — of between five and eight years. Those who confess after the start of their trial may be subject to five to eight years in prison, which could turn into non-jail sanctions if the culprit commits to reintegration through social work. And those who do not confess but are found guilty face up to 20 years in prison.

This does not mean that there will be no forms of amnesty whatsoever. While Santos said Colombia will grant as many pardons as possible to political crimes, and Timochenko stated that no member of the FARC’s highest cadres will be subject to imprisonment, certain crimes will not be granted amnesty. These include crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes such as kidnappings, torture, forced displacement, forced disappearances, extralegal executions and sexual abuse.

It remains to be seen whether the judicial measures agreed upon by the FARC and the government will effectively target those responsible for the violence unleashed in over 50 years of armed struggle. But even with its limitations, the agreement the government and the FARC have come to is no small achievement. Allegations that the rebels may be able to walk free once the treaty was signed had in the past severed the relationship between Colombians and Santos, whose approval ratings plummeted to 29 percent in April. That the forthcoming peace treaty now involves some forms of incarceration for those responsible for the conflict’s atrocities goes some way toward meeting the victims’ expectations.

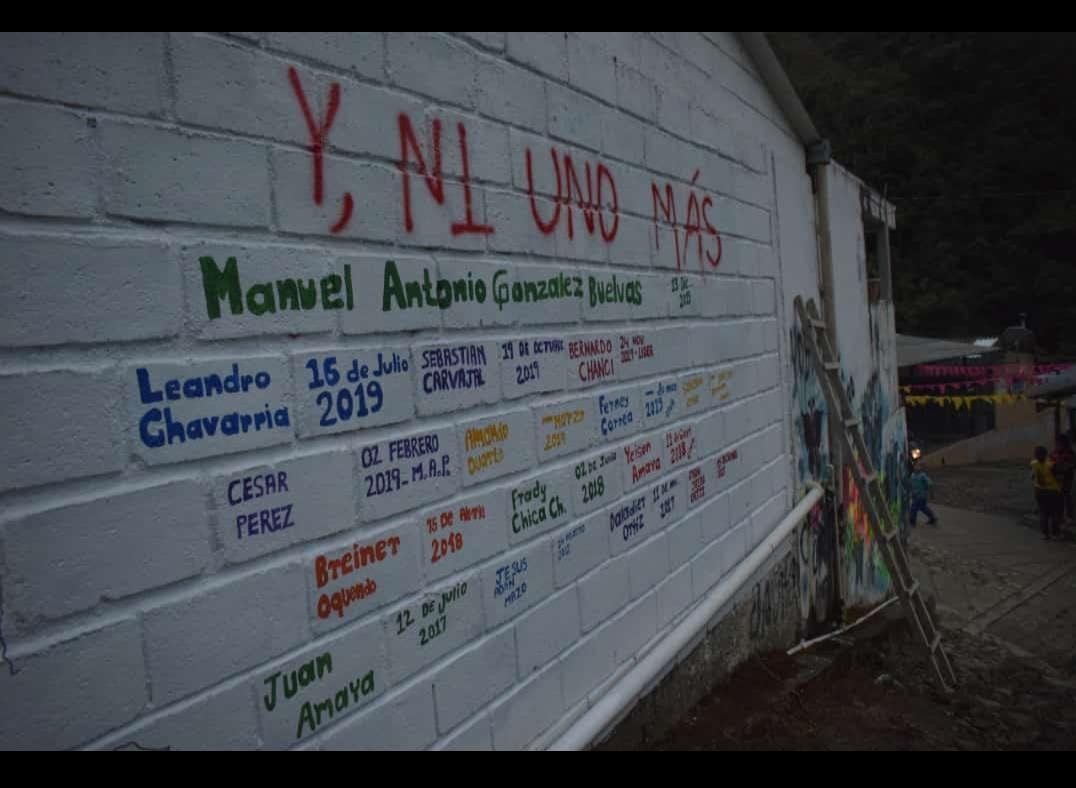

It is hard to predict whether the new judicial scheme will yield the sorts of punishments called for by those who have suffered the consequences of Colombia’s armed struggle. Both Santos and Timochenko have recognised the importance of the conflicts’ victims as the backbone of the peace treaty. Only an agreement that will pay justice to the thousands of casualties the conflict has left behind will lead to a durable peace. And a durable peace may only be achieved with the help of a judicial system that will allow for the uncovering of the truth behind the massacres, a degree of justice and reparation for their victims and the promise of no repetition. The new judicial framework established this Wednesday appears able to meet the challenge. Another much more difficult question is whether the government and the FARC will have the will to fully submit to it.

For now, it is nice to think the handshake between Santos and Timochenko will be remembered as a first step in this direction, and not just a historic photo opportunity.

About Leonardo Goi

Leonardo Goi is a researcher for FIP, Fundación Ideas para la Paz, a Bogotá-based study center that focuses on Colombia's armed conflict and its repercussions on the country's development.

< Previous Article

September 24, 2015 > Staff

Colombian President, FARC Rebels Say Peace to Come in Six Months

Next Article >