Andes, Colombia, Dispatches

Despite ‘No’ Vote, Colombian Indigenous Groups Say They’ll Implement Peace Accord

October 17, 2016 By Hanna Wallis

With a red and green bandana fastened around his neck, Colombia’s high commissioner for peace, Sergio Jaramillo, approached the edge of a stage adorned with fresh flowers as if walking to the edge of a precipice. Below him, 8,000 people hushed in anticipation. They wore the same colors, representing blood and land, each with the insignia of one of Colombia’s strongest minority movements: the regional Indigenous Council of Cauca, or CRIC. In the background, a banner hung like a limp sail with the black and white faces of dozens of assassinated indigenous leaders in a long, unnamed row. “A transition to peace in any part of the world is full of risks, full of doubts,” Jaramillo said. “We cannot let fear overtake us.”

When Jaramillo uttered those words in the indigenous reserve of La María, Cauca, less than two weeks had passed since the government finalized a peace accord with the leftist guerrilla group FARC, seeking to end over 50 years of armed conflict. On Oct. 2, the public voted against ratifying the deal, shocking the world with a “No” decision that won by a sliver margin of 50.25 to 49.75 percent.

For indigenous communities like the crowd in La María, that outcome was unacceptable. Colombian indigenous leaders say they’ll move forward with the peace accord anyway, contending that their communities have borne the brunt of a conflict that has claimed an estimated 220,000 lives, 81 percent of them civilian.

“Indigenous and Afro-Colombians cannot wait for a solution to this crisis while the Colombian government makes institutional adjustments,” an official CRIC statement said on Oct. 4. Luis Fernando Arias, the president of the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia — ONIC, in Spanish — said in a radio interview the day before, “We believe that the victims of this conflict voted in favor of the accord, and this is legitimate.” Both organizations called for continued U.N. security monitoring to uphold the bilateral ceasefire in effect as of Aug. 29.

The unexpected outcome left the country in a vertigo of unknowns. The referendum was an all-or-nothing arrangement with “no Plan B,” and polling before the vote erroneously forecast a safe approval victory. Now, it’s unclear what will become of the result of four years of negotiations in Havana to resolve the oldest armed conflict in the Americas.

“There are several possible routes forward,” José Domingo, a top leader from CRIC, told the Dispatch in an interview. “In every case, it’s going to be very complicated.”

Indigenous groups’ stake in the peace process has a different gravity than for many other Colombians. The violence has not torn through the country uniformly — it concentrates more heavily in the countryside, afflicting indigenous, Afro-descendent and campesino communities disproportionately. Colombia has the highest number of internally displaced people in the world at over six million, many of whom are ethnic minorities, a 2015 Amnesty International report found.

The areas of the country most victimized by the conflict and considered most vulnerable during the post-conflict, like the southwest department of Cauca, largely voted “Yes” for the peace agreement with generous majorities.

Depending upon how the country reshuffles the peace process, minority groups could potentially experience new waves of violence, get pushed out of the negotiation process or lose their hard-fought protections from the 1991 constitution that recognizes Colombia as a multiethnic, multicultural country. With so much to lose, indigenous authorities want to uphold the terms of the existing agreement at a local level.

On Oct. 21, three municipalities in Cauca — Toribio, Corinto and Jambalo — will begin collecting signatures that allow local leaders to implement the accord in their territories. This process relies on a constitutional process called “open council,” which establishes public consultation rights.

“We don’t want an accord that is only between elites,” Domingo said. “With our local authorities and our own communal organizations, the peace accord doesn’t necessarily have to be imposed; we can find a way to apply it for ourselves.”

Like the half century of conflict itself, the referendum vote carved up the population along different allegiances, just as messy as the violence that necessitated it. Many opponents — most prominently former President Álvaro Uribe, a vocal defender of the “No” campaign against the peace deal — argued that the agreement allowed for impunity of guerrilla members who perpetrated war crimes. Critics felt it offered too many concessions to the FARC, a group the U.S. State Department continues to categorize as a terrorist organization.

Minority movements were also skeptical of the accord, but for different reasons. Indigenous communities have constitutionally recognized collective land ownership rights that prevent division of their territories from individual purchase or sale. Beginning in 1971, indigenous people in Cauca began a movement under CRIC to reclaim their ancestral land and self-determination. Today, indigenous collective lands, known as “resguardos,” have a parallel self-governance structure from the central state.

Although international law reinforces the same rights under the International Labor Organization’s convention 169, indigenous leadership feared that aspects of the peace agreement could undermine their independence.

“We are going for the yes vote, but in a critical way,” indigenous counselor Nelson Lemus told the Dispatch. On a national scale, the indigenous movement consolidated around the “Yes” vote under certain conditions– “Yes, but with guarantees to protect our territories, our communities and our autonomy. Yes, but with demilitarization,” Lemus said.

Lemus participated in the Ethnic Commission that represented minority interests in the Havana negotiations. Since the beginning of the peace dialogues in 2012, Colombia’s indigenous movement, led by the CRIC and ONIC, sought participation, arguing that whatever the government and FARC decided upon to end the conflict must take into account their unique forms of autonomy. Although the Ethnic Commission formed in 2015, it wasn’t until June of this year that they paid their first visit to Havana, and it wasn’t until three hours before the dialogues closed that they succeeded in appending an ethnic chapter to the 297-page peace agreement.

“You could say that the Ethnic Commission didn’t participate until the final hours of the negotiations,” Jaramillo said in La María. “But you could also say that they were the only ones to make it to Havana at all.” The chapter enshrines their right to consultation and direct leadership for any projects occurring in their territories, like rural development initiatives or the placement of “concentration zones” where FARC combatants were supposed to demobilize and hand over their weapons.

The week after the vote, hundreds of people in Cauca mobilized a caravan atop brightly painted “chiva” busses to Bogotá as a protest of the decision. The procession culminated at the ONIC’s national congress, where 7,000 indigenous people converged from all over the country to show their commitment to implement the peace agreement.

“In whatever way, the war necessarily cannot continue,” CRIC counselor Favio Alonso Avirama said. “We support the peace process with all of the uncertainties there have been, even if from here forward, we must make some modifications.”

Still, if the FARC and government return to negotiations to revise the peace deal, they will likely have to adapt it to placate its strongest detractors. Uribe and his supporters in the Democratic Center party have insisted that guerrilla war criminals must receive harsher punishments. His platform of “peace without impunity,” however, does not account for the culpability of other armed groups beyond the FARC; the Colombian armed forces and paramilitaries groups also committed egregious human rights violations, with the latter accounting for three times as many massacres as the guerrilla.

Many concerns linger for indigenous and Afro-descendent communities, who have endured violence from all sides while maintaining a peaceful position of neutrality. In an impassioned speech before the representatives in La María, prominent indigenous leader Aída Quilcue read the latest threat from the paramilitary group the Aguilas Negras. Just a day after the meeting in La María, a campesino woman in Cauca who was a vocal peace leader was assassinated. Most people in the area presume that paramilitaries committed the killing to intimidate “Yes” voters.

Quilcue acknowledged all of the victims, like her husband and the 27,016 other indigenous people in Cauca slain in the conflict, who could not be present to witness the historic meeting. Her eyes were wet, though her voice remained poised and commanding. “We applaud the victims during this moment of great achievement,” she said. “Today, the end of conflict is announced.”

For some communities in the epicenters of violence, Quilcue’s pronouncement already spoke to a palpable shift. In Toribío, Cauca, a predominantly indigenous town that suffered more attacks by the FARC than almost any other place in Colombia, the population has now lived almost two years without a single hostility, which the mayor Alcibiales Escue attributes to the negotiations. Eighty five percent of voters from Toribío supported the accord. Escue acknowledged that constructing peace will require many decades of reconciliation, but it helps to start from a foundation of tentative tranquility.

With all of its gaps and uncertainties, the peace accord represented a profound opportunity for Colombia to transition into a new chapter of post-conflict. At the U.N. General Assembly in September, all 15 members of the security council unanimously voted to support it. Now that the Colombian population has struck it down, maybe the country’s minority groups will lead the effort to turn the page.

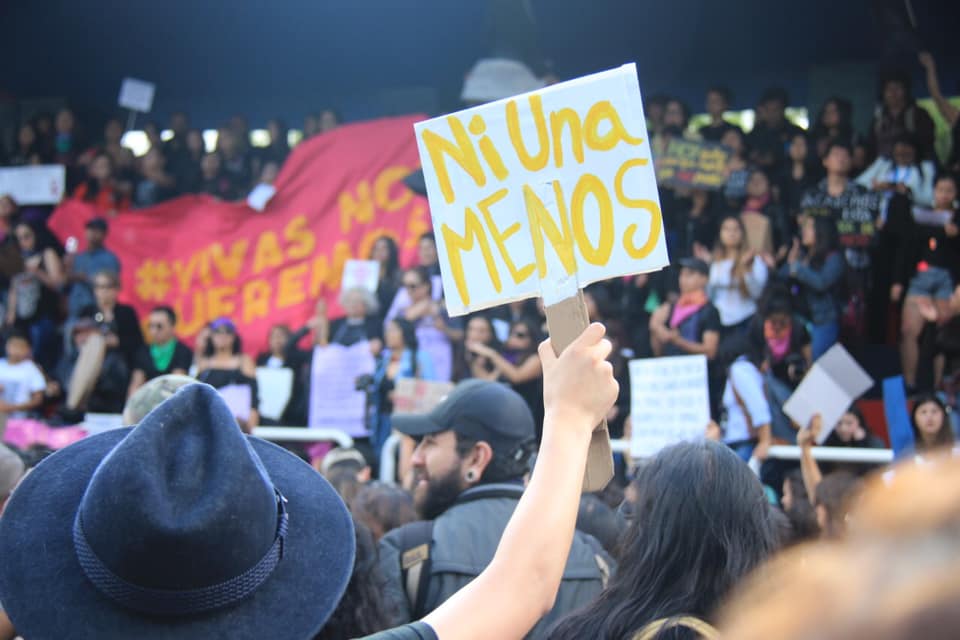

[supsystic-gallery id=1 position=center]All photos by Hanna Wallis

About Hanna Wallis

Hanna Wallis is a writer and filmmaker focused on indigenous issues in Latin America. She received her masters in Global Journalism at NYU, where she began reporting on the Colombian peace process. Her video and written work has been featured in Fusion, The Huffington Post, Latino USA, and the North American Congress of Latin America. She is currently developing a film about indigenous resistance in Cauca, Colombia.