Andes, Caribbean, Dispatches, Haiti, Mexico, News Briefs

Communities in diaspora are using language to resist assimilation

November 15, 2018 By Leo Schwartz

NEW YORK — Three days a week, the sounds of Haitian Creole fill the fourth floor of the King Juan Carlos I Center in Manhattan’s Washington Square Park. The source is a class taught by Winnie Lamour, a professor at New York University and the founder of the Haitian Creole Language Institute, which she created following the catastrophic earthquake in 2010 as a way to keep the larger Haitian community connected through language classes. Along with Haiti’s population of nine million, Haitian Creole is spoken by about one million Haitians who live in the United States, from New York City to Minnesota.

Haitian Creole is a blend of French vocabulary and West African grammar, a language created out of necessity by slaves as a means of communication. While Haitian Creole is not an indigenous language, it is part of the Indigenous and Diasporic Language Consortium (IDLC), a project between New York universities to teach and promote languages like Haitian Creole, Mixtec and Quechua. Lamour, along with a number of other organizations based in New York, use language to preserve marginalized communities that might otherwise be lost to assimilation and persecution.

The need to protect indigenous and diasporic communities has taken on a greater dimension of urgency with the election of Jair Bolsonaro as president of Brazil on Oct. 28. His campaign was filled with vicious rhetoric targeting Brazil’s indigenous population, such as asserting that “not one centimeter of land will be demarcated for indigenous reserves” and that “Indians smell, are uneducated and don’t speak our language.”

Bolsonaro’s words drove his supporters to action. The night of his election, 15 indigenous Guarani-Kaiowá people were shot, including a 9-year-old, by unknown gunmen in the southern State of Mato Grosso Do Sul. On the other side of the country, in the northern state of Pernambuco, the sole school and outpatient clinic serving a community of indigenous Pankaruru people was completely destroyed by fire. The Pankaruru took to Facebook to share the crime with the world, posting pictures of the wreckage with the message, “The barbarism has begun.”

Since the dawn of colonization, indigenous communities throughout Latin America have been persecuted and marginalized. Nearly eight percent of Latin America is indigenous: a population of about 42 million people. Indigenous communities face significant structural barriers, and constitute 14 percent of the poor and 17 percent of the extremely poor in Latin America, according to the World Bank. Their most significant threat, though, is extinction. Indigenous culture and language is quickly dying, through active targeting by leaders like Bolsonaro and the more passive processes of assimilation and diaspora. Many indigenous people move to urban areas or leave their countries all together, often moving to the United States. Once they leave their homes, they become even more marginalized, losing connections with their cultural heritage.

“People in the diaspora struggle with being connected. It’s hard to keep Haitian culture as your dominant culture when it’s not the dominant culture in the space where you live.”

In an interview with LAND, Lamour of the Haitian Creole Language Institute said diasporas are a major driving force to the loss of cultural heritage: “People in the diaspora struggle with being connected. It’s hard to keep Haitian culture as your dominant culture when it’s not the dominant culture in the space where you live.”

Lamour calls Haitian Creole a language of revolutionaries because it is a blend of the indigenous African languages of Haitian slaves and the language of their colonizer, developed by those who broke the yoke of slavery and created change. Through programming and classes at the Haitian Creole Language Institute and New York University, Lamour works to ensure the diasporic Haitian community can tap into that cultural power.

The indigenous languages of Latin America like Quechua and Mixtec could better be described as languages of resistance, having withstood 500 years of colonization. South America alone is still one of the world’s most linguistically diverse areas, with 448 languages spoken across the continent. Of those, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has classified 108 as endangered.

Like Lamour, other activists, artists, and teachers are using language as a tool for cultural promotion and strengthening. Quechua is the mostly widely spoken indigenous language in Latin America, with more than 10 million speakers spread over Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, Bolivia, Argentina and Colombia. The language is also prominent in the United States, and especially in New York City.

Charlie Uruchima was an undergraduate at NYU when he began to take Quechua classes with Odi Gonzales, a poet and professor. Uruchima was born to Ecuadorean immigrants, but did not grow up speaking Quechua (or the Ecuadorean variation, Kichwa).

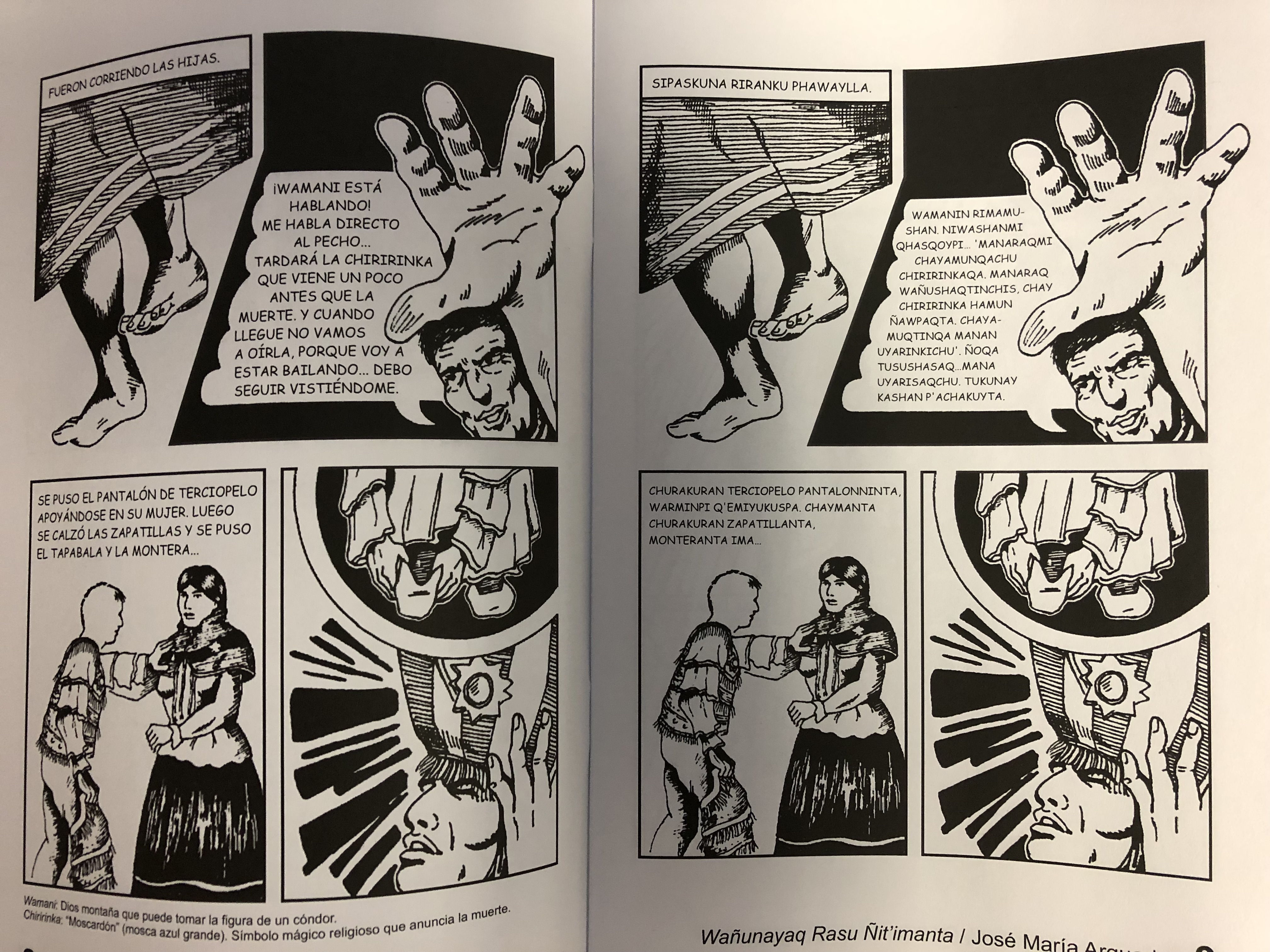

Credit: Walter Ventosilla and Odi Gonzales, URPI Editores

In an interview with LAND, Uruchima said that he always had a curiosity to learn Kichwa. He heard certain phrases from his parents growing up, but never thought of it as a language on its own: “When I could learn it at NYU, though, it was holistic. I wasn’t just learning a language on its own, but I was learning the context around it.”

The walls of the context, though, were collapsing. While New York’s Ecuadorean population is more than 130,000, only around 10,000 speak Kichwa. As a marginalized subset of an already underrepresented community, many Kichwa speakers were hesitant to to communicate in their native tongue. Uruchima stayed at NYU for his master’s degree, seeking to strengthen his community in New York, and create connections with its shared heritage back in Ecuador. With two other Ecuadorean immigrants, including the owner of a DIY Ecuadorean radio station, they started the first radio station in the United States that would broadcast in Kichwa, and named it Kichwa Hatari, or “raising Kichwa.”

Kichwa Hatari is for “folks who felt their language had been stripped from them,” according to Uruchima. “Language is a tool to bring people in and create this sense of community and to distinguish ourselves more as an indigenous community, as natives of the Americas, no longer falling into this liminal space of not belonging.”

Kichwa Hatari also creates a bond between diasporic communities and those back in Ecuador. From a small sound booth in the Bronx, it has been broadcasting every Friday night since 2014. “We use our own voice to amplify the situations happening on the ground over there,” said Uruchima.

His teacher back at NYU, Odi Gonzales, also believes in language as a medium for preservation, which he has employed in his “La Agonía de Rasu Ñiti” project. As a semester-long workshop with his Quechua class at NYU, Gonzales and his students translated the legendary Peruvian story into Quechua. He then had his friend and illustrator Walter Ventosilla create accompanying pictures, which they compiled into a comic book written in both Spanish and Quechua. The book was just released this year.

One of the most famous Peruvian authors, José María Arguedas, originally wrote the story “La Agonía de Rasu Ñiti” in the 1960s after researching movements of resistance against the Spanish Crown during the period of colonization. Instead of fighting back against the Spanish through battle, some indigenous resistance fighters fought back through the artistic expression of the danza de tijeras, or the scissor dance. Scholars believe the dance evolved as a reaction against colonialism and the repression of indigenous culture. Wearing elaborate costumes and wielding iron rods, the dancers would compete against each other for hours on end in a feat of strength, will and endurance.

“La Agonía de Rasu Ñiti” chronicles the dying words of one of these dancers, passing his final testimony on to a fellow scissor dancer as a way of keeping the tradition alive. While Arguedas was fluent in Quechua, the story was originally written in Spanish, although with Quechua syntax.

In an interview in Spanish with LAND, Gonzales said that the motivation for the translation project was not only linguistic, but to share the story with a broader audience. Having the text in a comic book format makes it that much more digestible.

Like Uruchima, Gonzalez sees that most media consumed by indigenous populations is exclusively in Spanish, especially for children. With the comic book, he has created a way for children to learn Quechua and Spanish side by side: “For all the kids who speak Quechua, they can continue speaking it so they don’t lose the language.”

A similar project, out of Mexico, is 68 Voces. Created by the filmmaker Gabriela Badillo, 68 Voces is a collection of animated shorts, each narrated in one of Mexico’s 68 indigenous languages, such as Mixtec and Nahuatl. The films—all just a minute or two—each tell a story from a Mexican indigenous culture: a fable, an origin story or a myth. Each film is illustrated with its own style, ranging from rich abstract figures to sparse minimalist landscapes that match the complex rhythms and sounds of each individual language. Badillo sought collaborators for the shorts, as the films are narrated by the elders and often co-illustrated by the youth of each community. All of the films are available to watch online.

Celebrate Mexico Now, a weeklong festival that takes place every year in New York, brought Badillo’s project to showcase the beautiful layers of Mexican culture. According to Claudia Norman, the founder of Celebrate Mexico Now, 68 Voces is a way to spread awareness of the need for indigenous culture: “As these languages are disappearing, 68 Voces is a testament and a statement—a reminder that this is something we have to preserve.”

Indigenous and diasporic communities have faced marginalization for centuries, yet they continue to fight to protect their heritage. Today, that preservation has never been more necessary. With xenophobia already permeating American discourse, Bolsonaro’s election and his impact on the region will pose even more threats to the vulnerable communities of the Americas.

To each of these activists, educators and artists, the best way to protect their cultures is to celebrate them and to share them, especially in the face of barbarism. As the threat of hate and ignorance grows throughout the Americas, these organizations believe in the power of communication and language as the most effective tools to fight back.

About Leo Schwartz

Leo Schwartz is a journalist and researcher pursuing a master’s degree in journalism and Latin American studies at NYU. His reporting has appeared in Roads & Kingdoms, Street Sheet, and Cinema Escapist, and he previously worked as a producer at The Players’ Tribune. His research interests include freedom of the press and the rise of digital media in Latin America.