Andes, Dispatches, Ecuador, Features

‘Todos Somos Martha’: Ecuadorians Protest Gender Violence, Femicide and Xenophobia

March 27, 2019 By Gabriela Barzallo

QUITO — For two days in January, thousands of people mobilized on the main avenues of Quito, Guayaquil and several other cities in Ecuador, protesting sexual violence, femicide and xenophobia. Days earlier, a group of men gang raped a 35-year-old woman in a bar in northern Quito and a pregnant woman was murdered by her Venezuelan partner in front of the police in Ibarra, sparking a wave of violence against Venezuelan refugees in the city. With these two cases, there are now approximately 600 registered femicides in Ecuador since Jan. 1, 2014.

The 35-year-old woman, Martha, whose rape led to the mass mobilizations, was drugged and tortured by three men she considered close friends, she said in a testimonial. The men, who recorded video of the rape on their cellphones, were immediately detained by the police and are now awaiting their sentences. The collective outrage went viral on social media. Thousands of Ecuadorians, using the hashtag #TodosSomosMartha (#WeAreAllMartha), condemned the crime and organized peaceful marches on Jan. 20 and 21 to demand justice for victims of gender-based violence around the country.

Gender violence is a structural problem in Ecuador, with roots in patriarchal practices and machismo, said Ann Frias, an Ecuadorian sociologist and gender studies analyst, by phone.

“People have unconsciously normalized gender violence within the country,” Frias said. “It is common for women to the be victims of street harassment, either verbal and even physical. However, their acts are seen as normal, and nobody says anything about it, without realizing that crimes and violations like these start with attitudes like these, that diminish women.”

“I want to grow up unafraid of being free.” Parents with children also attended the protest. According to the National Network of Shelters, of the 600 women who have died as victims of femicide since 2014, 7 percent were younger than 5 years old. (Photo by Gabriela Barzallo)

A day before the first mobilization, another case of femicide went viral on social media. The victim, a 24-year-old pregnant woman named Diana, was held hostage and stabbed by her Venezuelan partner, according to the victim’s father. Dozens of people, including police, witnessed the crime. The next day, President Lenín Moreno issued a press release on his Twitter account announcing that he had ordered “brigades” to control the Venezuelans in Ecuador.

“We have opened the doors, but we are not going to sacrifice anyone’s safety,” Moreno said his statement.

Minutes after Moreno posted on Twitter, protesters in Ibarra started invading houses and hotels where hundreds of Venezuelan refugees were staying. The protesters destroyed and burned their belongings, blaming them for the murder of Diana. At the same time, hundreds of people protested against this act of revenge, saying the president’s statement was xenophobic. These protesters joined those demonstrating against sexual violence and femicide the next day. Since the attacks, dozens of fearful Venezuelans have returned to their country through the “Return Home” plan, and, according to reports from the Venezuelan consul in Ecuador, the number of requests exceeded 700 in January.

“I am marching because violence is not only physical, but cultural, when you justify abuse by saying that women should not go out, or do what men do,” 25-year-old Estefanía León said at the protest. “I am marching because I do not want to live in a country where the nationality of the assassin is more important than the victims themselves. I am marching for all those women, from all ages, including children, whose lives have been lost. It is time to stop impunity.”

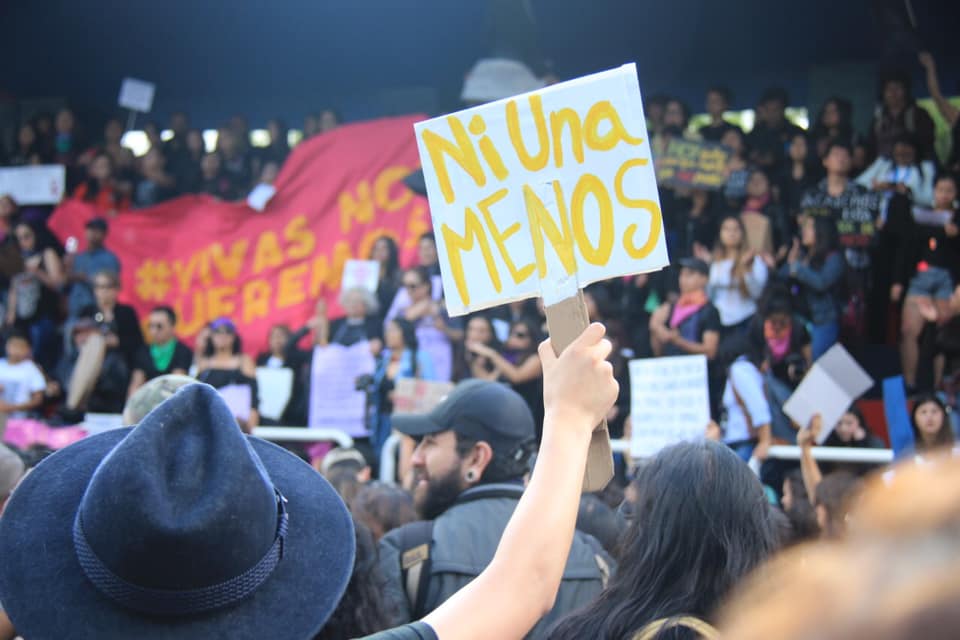

León joined the “Ni Una Menos” (“Not One More”) movement in Ecuador three years ago after her best friend was killed by her boyfriend, who has yet to be punished by the justice system. León was one of the thousands of men and women at the January protests who dressed in black and carried banners with phrases like “Machismo kills, xenophobia too,” “Machismo is not fought with xenophobia” and “Crime has no nationality.” Daniel Espin, a 35-year-old husband and father, attended the protest because he believes it was a moral and societal obligation.

“I am a father and I do not want my daughters to live in a country where they are at risk every time they go out just because of their gender,” Espin said at the protest. “We are facing a structural problem, in which politicians and the state focus more on blaming others rather than finding a reliable solutions to end crime. If we do not fight patriarchy and categorically reject xenophobic practices, we are failing as a democratic society.”

With slogans and banners, and dressed in black clothes, protesters demanded justice for Martha, Diana and over the 600 women who have been victims of femicide since 2014. (Photo by Gabriela Barzallo)

The protest reached the General Prosecutor’s Office of the State, where, in a symbolic act, the leaders of feminist movements lit giant torches with a manifesto against “the lack of justice for women,” the victims of harassment, violence, abuse, rape, kidnapping and femicide.

According to the National Network of Shelters, about 600 women have died in Ecuador as victims of femicide since 2014, but only 75 were registered in 2018. Of the 600 women, 64 percent were between 14 and 36 years old, and 7 percent were younger than 5 years old. In 66 percent of the cases, the crime was committed by the victim’s partner or ex-partner, in 7 percent of cases, by their father or stepfather. These femicides left behind 111 orphaned children.

The protest reached the General Prosecutor’s Office of the State, where, in a symbolic act, protesters lit candles and torches rejecting the lack of justice for the victims of harassment, violence, abuse, rape, kidnapping and femicide. (Photo by Gabriela Barzallo)

Frias, the sociologist, said that rapes, femicides and other abuses occur on a daily basis, but most are never prosecuted. Diana’s and Martha’s cases are the exception.

“After the cases of Martha and Diana went viral local authorities took rapid preventive measures, mainly because there were videos proving the crimes, and since one of these videos went viral, they have the pressure of an entire country demanding justice,” Frias said.

The offenders in both Martha’s and Diana’s cases are currently being held in the Latacunga prison awaiting trial, and protesters demand they be sentenced for up to 29 years in prison, the maximum sentence for such crimes. In February, Diana’s family, who is now taking care of her two orphaned children, sued the 25 police officers who allegedly witnessed the crime.

The outrage about Diana’s and Martha’s cases have crossed borders. Ecuadorians around the world have demanded justice, recognizing the lack of empathy of the governmental authorities. Jocelyne Enriquez, a 21-year-old Ecuadorian immigrant living in New York, said she feels deeply impacted both as a woman and as a migrant. She believes that Moreno’s actions are reminiscent of the xenophobic policies of President Donald Trump in the United States.

“I feel a lot of empathy for the displaced Venezuelans who were victims of xenophobia in Ecuador,” Enriquez said. “As a migrant, I understand how difficult it is to be in a country where you are judged or tagged by negative stereotypes towards your culture or place of origin. However, what I found positive about all this is to see how the feminist wave movement is growing in there. It is very uplifting to see girls of my age go out and protest without fear. It was not like that five years ago. This generation seems to be more socially engaged. I hope this fight is constant and not forgotten.”

About Gabriela Barzallo

Gabriela is an Ecuadorian journalist who holds a B.S. in Media, Culture and Communication from NYU. She held a multimedia journalism internship at Diario Tiempo Argentino in Buenos Aires, where she produced stories focused on ethnic minorities, such as the invisibility of Afro-Argentines in the Argentinean traditional history and public sphere. She has also freelanced for several media outlets in Ecuador and New York. Her reporting and research interests include foreign and investigative reporting, gender violence, migration, ethnic minorities and international politics. Twitter @gabybarzallo