Dispatches, Features, North America, United States

From ‘Just a Mom’ to Immigration Activist: Salvadoran TPS Holder Fights to Keep Her Family Together

June 3, 2019 By Colleen Connolly

By the time the alarm went off at 2 a.m. Cecilia Martínez had only slept for three hours, but Feb. 12 was an important day. So despite her exhaustion, she did not roll over and go back to sleep. Instead, she grabbed her phone and started making calls to Long Island.

Martínez was in a hotel in Washington, D.C., awaiting the arrival of four buses carrying her friends, neighbors and some strangers. Most of them were Salvadoran immigrants, just like she was. It was her job to make sure those four buses made it to Washington by 8 a.m. But one had broken down.

As she worked the phone, trying to get the bus fixed, Martínez was keenly aware that the clock was ticking: 6.5 hours until the rally, 209 days until she might be forced to leave the United States, where she has lived for two decades. Martínez is not one to sit idle and wait, however. So she kept working — for her own family and the families of thousands of others.

“They’re humans just trying to keep their families together and keep working in the country that we believe is home,” Martínez said. “And it’s just heartbreaking that we have to go through this whole thing with our children, take them out of school to go do this stuff so we can have our voices heard. Because no one’s doing anything for us.”

Martínez is one of nearly 200,000 Salvadorans who were ordered to leave the country after the Trump administration rescinded their Temporary Protected Status (TPS), the legal status granted to immigrants from countries devastated by war and natural disasters. The February rally in Washington was meant to be a show of force from Martínez and thousands like her who demanded a path to citizenship, a right they currently do not possess.

For Salvadorans, TPS offered short-term refuge after a pair of earthquakes struck the country in 2001. But Martínez, 37, has already spent more than half of her life in the United States. She learned English here and found jobs nannying and cleaning homes and office buildings. She found love and marriage, and later heartbreak and divorce. She became a wife, a mother and then a single mother. Her teenaged children are U.S. citizens. For Martínez, the battle is about more than citizenship papers. She is fighting for the right to nurture her roots in her Long Island town and to watch her children grow up. She wants to belong, to stake her claim to a country that has become her home.

Martínez stayed awake in that hotel room until she finally got the news: the broken bus had been exchanged for a working one, and the passengers were on their way. By 8:30 a.m., on that cold and rainy morning, the Long Island delegation of TPS holders had joined thousands of others in front of the White House in a sea of ponchos and winter hats.

Cecilia Martínez, center, stands in front of the White House during a National TPS Alliance rally in February. (Photo courtesy of Proresidencia TPS)

Three weeks later, there was more good news: The Trump administration announced that Salvadorans would be given an additional four months to stay in this country. The new deadline for their departure is Jan. 2, 2020, a date now cemented in Martínez’s mind. In the meantime, a bill has also been proposed in Congress that would offer TPS holders a path to citizenship. The House of Representatives is expected to vote on it in June.

Before President Trump announced his plans to end the TPS program, Martínez only thought about it once every 18 months, when it was time to file the paperwork to renew her legal status. Now, she says, she thinks about it every day.

“I was just a mom before all this,” Martínez said. “I was just a mom working, going day by day. Then the fear of deportation came, and there’s no way we can go back. So I became an activist.”

***

Martínez was a child living in Santa Ana, El Salvador, in the 1980s when the first debates began in Congress about granting relief from deportation to Salvadorans in the United States. El Salvador was mired in a civil war, and the United States was sending billions of dollars in economic and military aid to support the right-wing government against leftist guerrillas. More than 75,000 people died before the war ended in 1992 and thousands fled north. But most of the immigrants were denied asylum for political reasons, according to Cecilia Muñoz, vice president for public interest technology and local initiatives at the think tank New America. So lawmakers in Congress began hammering out a solution.

Throughout the 1980s, Rep. Joe Moakley (D-Massachusetts) and Sen. Dennis DeConcini (D-Arizona) tried to pass legislation to stop the deportation of Salvadoran asylum seekers. They finally achieved their goal with the passage of the 1990 Immigration Act, which created TPS. Salvadorans became the first recipients. It was a victory, but it was also a compromise. Muñoz, who witnessed the debates and later became President Barack Obama’s top immigration advisor, said citizenship was never on the table.

“The idea behind the legislation was to give people, temporarily, the ability to stay when there were circumstances in their country which made it dangerous to return them,” Muñoz said. “But the construct was built on the notion that it be temporary, and frankly I don’t think it would’ve passed if the argument was ‘there has been a hurricane and, therefore, everyone who is from that country who is in the United States right now gets to become a citizen.’”

Questions remained. How would the government determine when to send TPS holders back to their countries? Salvadorans were told to return home for the first time after the country’s civil war ended in 1992. But the war-torn country’s economy was in shambles and the memory of violence fresh. So the U.S. government offered Salvadorans another option: apply for Deferred Enforced Departure, or DED, a status that’s similar to TPS. When that, too, expired about a year later, there was only one option left to stay legally in the country. Under the American Baptists Churches v. Thornburgh agreement, also known as the ABC lawsuit, Salvadorans and Guatemalans who had been denied asylum during the countries’ civil wars could reapply if they had been in the United States since 1990.

While the fate of the former TPS holders was being decided in the Supreme Court and in the Capitol, Martínez, then a teenager, was preparing for her own journey to the United States, not to flee war but to flee poverty.

“I came from a family that was really poor,” Martínez said. “We didn’t really have anything. I wanted to go to school and we couldn’t afford school. And then I had three sisters and one brother — my father left the home — and I was the older one. I was always looking for that opportunity to grow and to study and to help my brothers and sisters to have their careers, too.”

Seeing little opportunity in Santa Ana, Martínez moved to the United States alone, leaving her mother and siblings behind. She ended up on Long Island, standing on the streets of Hempstead and asking passersby, in Spanish, if they knew of work opportunities. One person eventually connected her to an Ecuadorian family in the area who needed a nanny. The family paid her $9 an hour, enough for her to pay her bills and send money back home.

In just a few years, Martínez was able to buy her family a house in El Salvador. But soon after, the earthquakes rattled the country, destroying the new house but also offering a glimmer of hope to Martínez and other Salvadorans in the United States. The destruction from the earthquakes was so severe that the United States granted Salvadorans Temporary Protected Status again. Martínez applied, and she has held the status ever since.

For 16 years, Martínez focused on raising her family and paying the bills. Then in the spring of 2017, the Trump administration announced it would end TPS for Haiti. Martínez knew El Salvador would be next, as Salvadorans make up the largest population of TPS holders, according to the Department of Homeland Security. In June of that year, the National TPS Alliance formed and held its first rally. Martínez joined right away.

***

Martínez’s 18-year-old son, Andrew, remembers the day that his mother came home and told him she decided to be a local committee leader for the National TPS Alliance. His first reaction was confusion. As her children grew up, Martínez told them she had a temporary legal status, but Andrew never thought much about it. But after the Trump administration threatened to end TPS, things started to change in their community and at home. Suddenly, TPS was a central part of their lives.

“I was trying to understand why she was not home at night,” Andrew said. “Before all this, she would just come home from work and make us dinner, and then after that she was just not here. She was on top of it 24/7 trying to fight for everyone.”

For nearly two years, Martínez has spent many evenings away from home, holding meetings and organizing rallies. Andrew and his sister, Gracie, 13, started to help out more around the house in their mother’s absence. They also started to learn about TPS and what that meant for their family.

If Martínez loses her immigration status, one of her biggest fears is separation from her children. Andrew and Gracie are U.S. citizens, and she worries about bringing them to El Salvador, especially Andrew.

In announcing its decision to end Temporary Protected Status for Salvadorans, the Department of Homeland Security pointed out that the disaster-related conditions caused by the earthquakes no longer exist. In other words, Salvadorans no longer need refuge. But environmental disasters are only one challenge that Salvadorans face.

El Salvador has one of the highest homicide rates in the world, and its gangs are notorious for their violence. Martínez fears that her teenaged son would be targeted. During one trip to El Salvador in 2013, anonymous gang members contacted Martínez’s ex-husband and asked for $10,000 in exchange for Andrew’s safety. As soon as Martínez found out, she arranged for her children to return to the United States immediately. They were out of El Salvador within 24 hours, without having to pay the $10,000. After that incident, Andrew said it would be “like suicide” for him to return.

Extortion is one of the main forms of income for the gangs in El Salvador, and there is little protection for people against these gangs, according to Adriana Beltrán, director of the Citizen Security Program at the Washington Office on Latin America.

“You have very weak institutions, widespread impunity and rampant corruption,” Beltrán said. “That means that if you’re from one of those communities and you’re a victim of violence, the likelihood that you will be able to access the justice system or get any kind of response from the state institutions is extremely low.”

Proponents of ending TPS, however, say that at some point, its recipients must return to their home countries. Ira Mehlman, the media director for the conservative think tank Federation for American Immigration Reform, says TPS is like a borrowed legal status, and Salvadorans have borrowed it for nearly 20 years. Eventually, they have to give it back.

“Conditions in that country are not ideal. They weren’t ideal before the earthquakes struck, and they’re probably not going to be ideal for the foreseeable future,” Mehlman said. “But there’s nothing in the TPS program that says it’s got to be the Garden of Eden before we can ask you to go home.”

This forces Salvadorans to make tough decisions to protect themselves and their families. Just a few years after the threats against Andrew, Martínez decided to renovate the home she had bought for her family in El Salvador in case she had to return. Her mother lives on the property still. One day, during the renovations, five men wearing masks and carrying guns broke into the house and threatened to kill the workers. Martínez’s mother prayed as the men surrounded her and asked them to leave, saying, “If you want to kill, go to the street. I have little children here.” The men eventually left and no one was hurt, but the family was shaken up.

“I stopped construction. I couldn’t complete it,” Martínez said, her voice growing higher as she remembered the close call. “I said, ‘I can’t bring my kids back there.’ I can’t because then they’re going to come after us, asking for money. That’s what they do. If they see a young kid, if you don’t pay them a certain amount of money, they’ll take them and kill them.”

On Long Island, Martínez’s children are safe from the gangs. But the threat of their mother’s deportation and the potential separation of their family looms.

The immigration status of a parent can have profound effects on a child’s mental health and wellbeing, according to Lisseth Rojas-Flores, a professor of marriage and family therapy at Fuller Theological Seminary. Rojas-Flores conducted a study about the psychological effects on children whose parents had been detained or deported and those whose parents were at risk of detention or deportation. She found that children who feared their parents would be taken away from them because of their immigration status were more likely to experience anxiety and depression.

“These children are probably reacting the same way as the children of unauthorized immigrants, meaning that they are anticipating that their parents might be deported,” Rojas-Flores said of the Salvadorans with Temporary Protected Status. “And you begin to see the anxiety symptoms and problems in school and so forth that we see with these other kids.”

Martínez knows her children worry that she might be deported. Her daughter, Gracie, recently won a writing contest for an essay arguing that families should stay together. She told Martínez once that she was determined to stay on the honor roll because she hoped it might help Martínez get a green card. Andrew, who is a junior in high school, has put his college plans on hold until he knows what will happen to his mother. He wants to be a pilot, but he told his mother he plans to work after graduation first and save money in case the family has to return to El Salvador, where there are fewer job opportunities.

“I want to see what happens with this whole TPS thing because it’s a family thing. I don’t want to lose my mom,” Andrew said. “I don’t want her to leave the country because after me, then it’s my sister graduating. Our family goal — we talk about this a lot — is to have my mom around when my sister graduates.”

Photographs in the Martínez home show Andrew meeting the pope in October. Andrew was part of a group of children of TPS holders who flew to Rome to ask the pope to intercede for them and their families. (Photo by Colleen Connolly)

Both Andrew and Gracie have become activists, too, just like their mother. Last fall, the National TPS Alliance coordinated a cross-country bus ride called the Journey for Justice, where TPS holders and their families rode the bus and raised awareness, stopping in 44 cities. Gracie and her mother joined the bus riders when they stopped in New York and traveled with them to Washington, D.C.

In October, Andrew flew to Rome to meet Pope Francis with other children of TPS holders. In front of the Vatican, they asked the pope to intercede on their families’ behalf. Martínez framed three photos of the meeting with Francis and hung them in the living room.

“We want to be here,” said Martínez. “This is the reason we came to the United States. We want them to be safe and to have a good education. And we work really hard for it.”

***

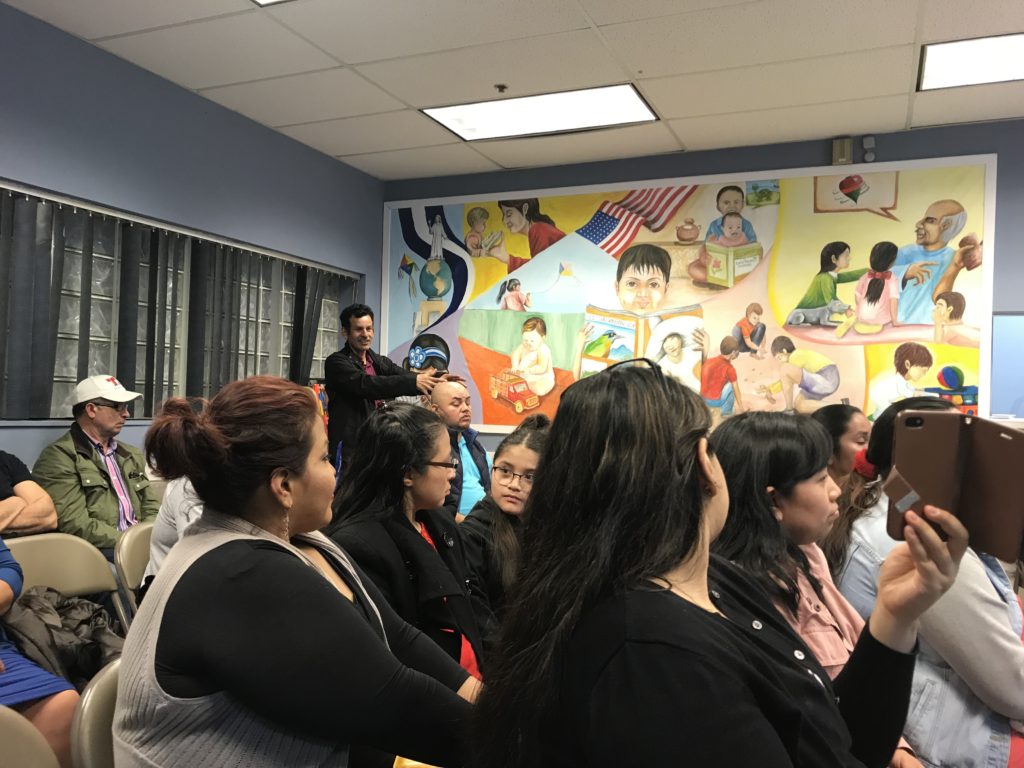

On a warm Saturday night in April, almost exactly two months after the Washington rally, about 40 people, most of them Salvadoran TPS holders, gathered at the Consulate General of El Salvador in Brentwood. The gray building is nondescript and easy to miss. From the street, a Salvadoran flag is the only noticeable sign that the building houses the consulate. Inside, however, everything brightens. A mural is painted on one of the walls, depicting an American flag and children playing with toys and reading books.

The meeting started slowly as people filtered in, greeting each other with a kiss on the cheek and chatting. As people eventually sat down, the room quieted. Several people looked around and whispered, “Where is Ceci?” Martínez, one of the Long Island coordinators for the National TPS Alliance, was late.

After the February rally, Martínez took a short break from her TPS activism. Ever since she found out Trump wanted to end TPS, she felt more and more sick. She was eventually diagnosed with diabetes, and her doctor advised her to undergo gastric bypass surgery to help with the side effects. She scheduled the surgery for the week after the rally, so it didn’t get in the way. She took a few weeks off from work to heal, but soon she had to return. By April, she returned to the fight, too.

At a National TPS Alliance meeting on Long Island in April, attendees asked questions about the Dream and Promise Act, which would allow TPS holders to apply for citizenship. (Photo by Colleen Connolly)

The National TPS Alliance has been filing lawsuits since they were founded in June 2017 to help keep TPS holders in this country. President Trump’s comment that countries designated for TPS were “shithole countries” was the basis of the first lawsuit, which alleged the administration’s decision was based on discriminatory anti-immigrant views. The lawsuits are still working their way through the courts so activists like Martínez are focusing on a permanent change in Congress, where TPS was born.

In June, the House of Representatives is expected to vote on the American Promise Act, which passed the House Judiciary Committee on May 22, along with a separate bill to protect people with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. The bill would allow recipients of TPS the opportunity to apply for citizenship. José Palma, a TPS holder from El Salvador and a Massachusetts-based coordinator for the National TPS Alliance, calls it “dream legislation.” The bill is unlikely to pass the Republican-controlled Senate, but support from Democrats in Congress gives many hope.

At the Consul General’s office in Brentwood, the meeting started without Martínez, with a fired-up call-and-response.

“Que queremos?”

“Residencia!”

“Cuando?”

“Ahora!”

Miguel Antonio Alas Sevillanos, the consul general, spoke next, telling the group that they are the “star of hope” for Salvadorans in the United States. Then each of the four Long Island committees was introduced. Right as Brentwood was announced, Martínez walked in with Gracie without missing beat.

“Buenas noches, bienvenida, y gracias por estar aquí,” she said.

Over the next three hours, the group discussed the proposed bill to protect them, including what was in it and why it probably would not pass. They also talked about ways in which they might convince their elected officials that they deserved to stay in the country. A large white screen displayed statistics from the Center for American Progress showing a breakdown by state of the billions of dollars that TPS households contribute in taxes each year — $25 billion in all.

Martínez nodded her head throughout the meeting and smiled at everyone she knew. She watched her daughter, Gracie, sitting with other children and scrolling through her cellphone. She watched as Andrew appeared in a video about the trip to Rome, displayed on a screen for all to see. These were her reasons for fighting.

“I want to give them that security that everything will be OK, that we’re not going to be sent back,” Martínez said. “But unfortunately, it’s uncertain. We don’t know what’s going to happen. Our faith in God is that we’re going to stay, and we’re going to keep fighting for it and asking for an opportunity to stay legally in the country.”