Dispatches, Features, Mexico, North America

Mexican Feminists Win Legal Protections Against Revenge Porn

March 17, 2020 By Molly McLaughlin

MEXICO CITY— Olimpia Coral Melo was 18 when a private video she had filmed with her long-term boyfriend began to circulate on WhatsApp. A tabloid in her hometown of Huauchinango, Puebla, printed her image on the front page, and soon the story made national headlines. Faced with abuse online and in person, Melo didn’t leave the house for eight months and attempted suicide multiple times.

“How was I going to defend myself if I had filmed the video?” Melo told BBC Mundo. At home, she tried to pass it off as a rumor, afraid of what her family might say when they found out, but her mother told her she had no reason to be ashamed. Having sex, she said, “Doesn’t make you a bad person or a delinquent… …It would be something to be ashamed of if you had stolen something or killed somebody.”

When Melo and her mother tried to report the individuals and media outlets who had shared the video to local authorities, they told her that no crime had been committed. Melo reached out to other women who had been through the same ordeal, and together they developed a legal reform that would criminalize non-consensual pornography (NCP).

In March 2014, less than a year after Melo’s own video was shared, the campaign officially began in Puebla. The reform to criminalize digital violence against women is known as the Olimpia Law in Mexico. Digital violence is defined as assault, harassment and threats, as well as the non-consensual sharing of personal information and sexual content via the internet. Nineteen Mexican states have adopted reforms, largely thanks to a vast network of activist groups operating under the banner of Defensoras Digitales (Digital Defenders) and affiliated with the Frente Nacional para La Sororidad (The National Sorority Front), an organization Melo founded.

Yucatán was the first state to specifically criminalize NCP, in May 2018. Ana Baquedano Celorio spearheaded the campaign, after her photo was posted to an NCP website when she was 16. She successfully shut down the page, which attempted to extort women using private images and videos. The page’s administrator, Bryan González, was sentenced to four years in prison. Melo’s home state of Puebla followed in December 2018.

In Mexico, NCP is often referred to as ‘packs’, which are sold, traded or used as blackmail via social media or dedicated ‘revenge porn’ websites. Some of this content is made consensually and then shared without consent, while other images are taken without the knowledge or consent of the victim. Reports of upskirting, for example, are a regular occurrence in Mexico City.

“In every state, there are at least five to ten women [campaigning for legal reform on this issue]. They’re like an army,” said Fernanda Gómez, a lawyer and academic with a focus on gender and technology, in an interview with LAND. Gómez attributes the success of the Olimpia Law to the powerful grassroots movement that Melo’s story inspired.

It is no surprise that young women have been particularly mobilized by this issue. According to a 2017 report, 66 percent of Mexican women over 15 years old have experienced some kind of gendered violence, both on and offline. However, women between 18 and 30 years old were found to be the most vulnerable in digital spaces.

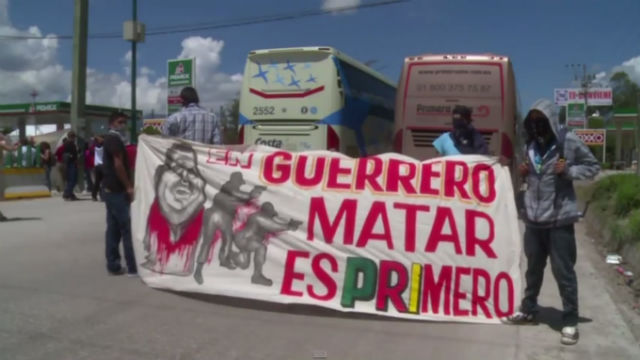

Ten women are killed in gender-motivated attacks everyday in Mexico. Less than two percent of cases end in a criminal conviction. Many see NCP as part of a spectrum of violence against women that includes femicide.

Data on the prevalence of digital violence in Mexico is limited, but anecdotal evidence suggests that increased access to smartphones and social media have facilitated a sharp increase in the spread of NCP. In the US, a Data and Society Research study released in 2016 estimated that one in 25 people are either threatened with or victims of non-consensual image sharing.

Gómez argues that digital violence is nothing new.

“The internet is not responsible for all this, it is just a tool,” she said. “It’s the same violence and asymmetries that we experience everywhere, but maybe it has just become easier to do it.”

She said gendered abuse and harassment online can be more far reaching than offline abuse, but women can use technology to their advantage. “You take a screenshot and you have the proof.”

However, Gómez is critical of the legislation-first approach that has come to dominate the discussion around digital violence. She emphasizes the need to educate young people and authorities, along with dedicating additional resources to investigate cybercrimes.

“I think that, with or without the reform, it’s extremely necessary to focus on prevention,” she said. “Our generation is discovering how the internet works and its consequences and impacts on our private lives in the future.”

Organizations like Luchadoras, R3D and Article 19 have also raised the issue of over-legislation.

“The whole Mexican system, including femicides, is based on drafting new crimes and raising the number of years someone has to be in prison,” said Gómez. The maximum jail sentence in Mexico increased from 30 to 140 years between 1931 and 2014.

“But we have an impunity rate of over 90%, so if you don’t pay attention to the other elements, like prevention and the way authorities react, nothing is going to change,” said Gómez.

Gómez also argues that the legal language in some of the Olimpia Law reforms is unclear or redundant. In states like Durango, for example, where sharing personal information was already criminalized, Gómez sees the addition of new crime specifically referring to sharing private images as a distraction, touted by politicians who seek to pay lip service to women’s demands.

Another thornier problem is removing the images from the internet once they have been shared to NCP websites or on social media. In many cases, the Olimpia Law provides victims with the support of the state to petition companies like Facebook or Twitter to take down their content. Given the track record of these companies though, Gómez is skeptical.

“With USMCA, the new free trade agreement between Canada, the US and Mexico, there are some provisions that I think are going to make it more difficult to tackle this issue with platforms that are not based in Mexico,” she said.

USMCA (also known as the new NAFTA) will generally enhance the free flow of digital content across borders. Under the agreement, platform providers, like Facebook and Twitter, will not be liable in the signatory countries for content users posted on their sites. It also includes provisions restricting the ability of the three countries to impose data localization requirements. Some exceptions, including for content related to sex trafficking, child exploitation and prostitution, may offer relief to victims of NCP, but their effectiveness is yet to be tested.

In Michoacán, the state’s penal code added the Olimpia Law in December 2019, carrying a prison sentence of four to eight years. Claudia Boyso, 23, a member of the Defensoras Digitales Michoacán, told LAND that the collective had pushed the reform for over three years. She said the resistance they encountered was more social than political.

“People were talking about sexting being a crime, when it’s not, it’s a sexual freedom,” said Boyso. “They don’t understand why somebody would send photos, with those kinds of comments that are blaming the victim.”

The group employed political tactics that were successful in other states, approaching relevant politicians and public officials and enlisting their support. Many people were already familiar with NCP. Boysho herself became aware of it in high school, when her male classmates had access to folders full of sexually explicit photos of girls and young women.

“It’s something that the whole world knows about, but we haven’t spoken about until now,” she said.

Defensoras Digitales Michoacán is working with 13 victims of digital violence to bring cases under the new reform. The group is also putting together a protocol that would be the first in the country to codify the investigative process of digital sexual crimes.

“It’s very important because right now, the victims don’t know where to go, and the authorities don’t even know where to send them,” said Boyso.

With the support of the Secretariat of Women’s Development, the protocol will define the types of violence that fall under the law, what victims should do to report it, the responsibilities of the authorities, and how the victim should be treated throughout the investigative and legal process. Defensoras Digitales Michoacán plans to hold trainings in schools and with the relevant authorities to increase the reach of the reform.

Ydalia Pérez Fernández Ceja, a lawyer with the Federación Mexicana de Universitarias (Mexican Federation of University Women), agrees that a protocol is necessary to support victims, who may fear their personal information being leaked to the press.

“Imagine if you go to the prosecutor, what guarantee do you have that your content will be respected?” she said. “That’s why people are afraid to report.”

Pérez Fernández said the establishment of a legal precedent is an important first step to combat gendered violence in Mexico.

“The whole concept of femicide as a specific crime was created by activists and formalized by the ruling of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in 2009, in response to what happened in Ciudad Juárez,” she said. “When you have a law, even if it is imperfect, it contributes to raising awareness of the problem and it serves to define what exactly we are talking about.”

In February, a 21-year-old man became the first person in Mexico City to be charged under the new reform. He had taken and shared without consent images of women in a bathroom at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. According to Pérez Fernández Ceja, the national university’s traditional role as a hotbed of feminist activism will help keep the case in the news.

“It’s going to be a good test of the law and help develop the system,” she said.

This high-profile case is also likely to assist women who are responding to threats and extortion related to NCP, serving as a deterrent and raising awareness of the potential legal consequences.

A contingent from the Frente Nacional para la Sororidad joined the historic International Women’s Day marches in Mexico City on March 8. As feminist groups throughout the country continue to agitate for social and political change in 2020, the Olimpia Law is a reminder of the important accomplishments of young Mexican activists.

Banner photo by Victorfotomx, via Flickr.