China, Southern Cone, United States

China, the Americas, and Lithium — A Tale of Investment in Emerging Markets

April 8, 2023 By Alfredo Eladio Moreno

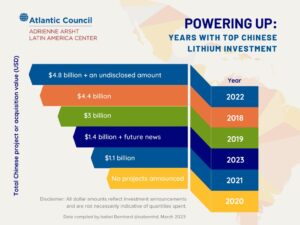

NEW YORK — Year-to-date, Chinese investments in Latin American lithium — as measured by the price tag of projects and acquisition value — have surpassed investment levels in 2021, according to the Atlantic Council’s Latin America Center. The same data show that investment levels dropped from 2018 through 2021, but then peaked in 2022 at over $4.8 billion USD.

A quarter into 2023, Chinese investments in lithium have surpassed levels from 2020 and 2021. (Twitter / Latin America Center, Atlantic Council)

Bilateral relations between China-Latin America ballooned at the turn of the century. Trade between China and Latin America grew at an annual rate of 31% from 2000 to 2009 and through the Great Recession. In monetary value, the volume of trade in goods increased from $14.6 billion USD in 2001 to $315 billion in 2020, according to fDi intelligence.

The figures reflect what’s known as the “commodity boom,” when Latin American supply of commodities — foodstuffs and minerals like copper — met Chinese demand for them. Though the erstwhile commodity boom of 2003-2012 is over, China’s investment trends in lithium indicate a vote of confidence in lithium’s potential, Latin America’s ability to supply it, and its own clout in the region.

Taking Stock of the Take-Off

The cover of the Economist’s Nov. 14, 2009 issue featured a curious image: Christ the Redeemer jet-propelled off the ground and into the sky, taking off to new heights. The title? “Brazil takes off.”

Nov. 14, 2009 cover of The Economist

The weekly magazine was in awe. A country “whose infinite capacity to squander its obvious potential [and] was as legendary as its talent for football and carnivals” had done the unimaginable: It had become an industrial liberal democracy, “whipped into shape” by privatization and openness — a “sensible set of economic policies,” said the magazine.

But if Brazil was taking off, then it was merely the bellwether: on its tail was a flock of Latin American countries also propelled by the commodity boom.

Outcomes were nothing short of stellar. Poverty decreased from about 27% to 12%, and inequality decreased by 11% between 2000 and 2014, reported the IMF. Although many countries in the region experienced a decrease in poverty, those benefits fell unequally across the region. South American countries, namely Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina, Colombia, Peru and Brazil, experienced drastically larger drops in poverty than Central American or Caribbean countries. Nicaragua’s 15% reduction in poverty pales in comparison to Ecuador’s 30% or Bolivia’s 25%.

What differentiated the South American countries from their neighbors was that they benefited from more favorable terms of trade, thus they were exporting significantly more than they were importing. Consequently, commodity sectors in these countries burgeoned, and opened up formal jobs for its population. Though the trend is imperfect, as the terms of trade skewed towards higher exports, so the gains in poverty reduction were higher.

Latin American countries took a mixed approach to the way they reaped the benefits of the commodity boom. While free market forces opened up employment to the labor force, leftist governments riding the Pink Wave also took the opportunity to institute social policies that put cash in the hands of its poorest. These policies varied, too. Bolivia and Peru began the non-contributory pension programs Renta Dignidad and Pensión 65, respectively. In Brazil, the conditional cash-transfer program Bolsa Familia provides monthly cash assistance to families on the condition they meet requirements related to the health and education of their children.

From 2003-2012, the spigot of money flowing into the region was on high, and China was the source. Commodity prices and trade revenues are volatile, however, thus more prone to global macroeconomic factors. For example, when oil prices began to slump in 2013, the Venezuelan economy had no other recourse but to witness a disaster: The economy shrank by roughly three-quarters between 2014 and 2021. As a whole, Latin American countries had to grapple with budgetary pressures as revenues slowed. Even so, a clear relationship had been established: China imprinted itself on Latin America.

Shifting Superpower Relations

Impressive ties were forged between Latin America and China during the commodity boom. By 2020, the value of trade in goods between China and Latin America increased 21-fold.

As a result, China unseated the European Union as the region’s second largest trading partner. While the United States still sits at the top of Latin America’s list of trading partners, China has become South America’s most important export market.

Gabriel Cohen, PhD candidate at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, sees China’s ascendancy in Latin America as a diversification in the options of superpowers with which to negotiate.

He told LAND that the United States’ relationship with Latin America today is an extension of Cold War policy, when there was no credible alternative superpower with which to negotiate. Since the commodity boom, that’s changed.

An emerging front in Chinese-Latin American relations has been development financing. “What we see is to some degree a turn to China because China would provide financing where traditional multilateral institutions — whether it be the IMF, World Bank, et cetera — would be more hesitant,” said Cohen. The demand for development financing is perennial, but the supply — from multilateral institutions or the private sector — can be finicky, since they are more risk-averse.

“China has become sort of a lender of last resort. There are political elements too. It has no problem taking advantage of the fact that debt strengthens its hand.”

Those political elements — namely, Sino-American rivalry — have strengthened as a result of the commodity boom, but have also benefited from U.S. policy since then.

Changing U.S. Policy

In 2013, Roberta Jacobson, Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs, said that the U.S. does “not in any way see China as a threat.” Chinese state news organization Xinhua then cited Jacobson’s comment at the Sixth China-US Sub-Dialogue on Latin America, saying that the U.S. sees more potential in partnerships with China in the region than adversity.

But the stakes changed during the Trump administration, when then-president Trump advocated, at least symbolically, for the retreat of the United States on the global front, and a more inward-focused policy. The implications of such a move are a matter of politics. Some material benefits might point to an answer, however.

For example, in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, China provided Latin American countries with its vaccine, what’s been called Covid diplomacy and what analysts say is “an effort to improve its image and curry favor with regional governments,” according to the Council on Foreign Relations. A country whose leader at the helm questioned Covid, might have coincidentally tarnished the reputation of the U.S. in Latin America, or at least weakened reliability.

Additionally, in some instances, China’s Covid vaccines did not come without strings attached.

Honduras and Paraguay, alleged that they faced pressure to renounce their recognition of Taiwan in exchange for doses. (Honduras has since renounced its recognition of Taiwan; Paraguay has not.)

If the symbolic retreat of the U.S. during the Trump administration strengthened China’s hand, then the Biden administration’s response since then has been a confident and “play-it-cool” rapprochement. At a meeting with Argentine president Alberto Fernández, Biden erred away from two topics: China and lithium.

“The US-Argentina relationship is increasingly characterized by mutual interest in developing lithium deposits and in defining China’s role in Argentina, in the latter case both in the area of China’s growing lithium investments and in other areas,” said Isabel Bernhard from the Atlantic Council.

The “play-it-cool” approach has been counterbalanced by one big move, however: the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity, a multi-sector and region-wide cooperative agreement that includes 11 countries accounting for 90% of the western hemisphere’s GDP. Without details hashed out yet, the power of the partnership remains symbolic.

All things considered, contracts with China remain seductive for their easy no-strings-attached nature, what Foreign Policy called a “tricky game.”

Lithium: Balls and Courts, Commodities and Markets

In recent years, Lithium has arisen as a sort of wunderkind. Some key expectations have been placed on the white metal, notably its importance to lithium ion batteries, or LIBs.

Energy experts and international business consultants alike agree on the increasing importance of the highly-reactive white metal. Demand hinges on LIBs, which are alluring for their superior capacity to store electric energy. LIBs can store up to 10% more energy than traditional lead-acid batteries, said the Inter-American Development Bank.

The demand for LIBs has increased since 2010. Demand is projected to increase nearly 1,700% (as measured in gigawatt-hours) by 2030. Additionally, LIBs are critical components of electric vehicles, which have experienced a boom in recent years.

The allure of LIBs in fueling the clean-energy transition are evident (even though lithium extraction can cause damage to the environment), and Latin America’s role in an emerging lithium commodity boom are obvious. Argentina, Bolivia and Chile — countries collectively known as the world’s “Lithium Triangle” — make massive contributions to the world’s supply of raw lithium. The Lithium Triangle and Peru contain 67% of the world’s known reserves.

Overall, they produce half of international supply. The industry was projected to reach a value of $7.7 billion by this year. It goes without saying that lithium is a cornerstone of these countries’ commodity sectors.

Not least, extracting lithium following a model of export-led development is seductive. But it could keep Latin America stuck in a “development loop” where the region benefits from the high of a boom, and then has to deal with the hangover of bust, Cohen told LAND. “It goes back to the age-old question of where do you spend your money when you get it?” he said.

A beneficial solution might be to create value-added products from lithium in the countries from which they are extracted, a solution that German Chancellor Olaf Scholz suggested in his visit to Argentina, Chile and Brazil this past January. The proposition would require the creation of adequate infrastructure in proposed mining sites.

A similar approach was announced by the Biden administration in February 2022. Known as the “Made in America Supply Chain,” the investments would prospect lithium mining sites in California and develop them to create domestic markets for the white metal. Two months later Mexico made an analogous move, its legislature nationalizing lithium reserves in the country, though the prospects of Mexico’s competitiveness in the emerging lithium market is up for debate.

Ultimately, more than lithium supply will determine competitiveness. Without development financing or favorable loans from able countries for the creation of critical infrastructure to add value to lithium products, lithium extraction and value-added production might be difficult. Not all economies are created equal, and not all states can afford to govern the same way as major superpowers.

Costs and Benefits of Symbolic Gestures

Similarly, the price for recognizing China is too high, Cohen told LAND. “How much can you still avoid China when all your neighbors are working with China?”

In this respect, Honduras’ renunciation of recognition for Taiwan is more than a campaign promise made by President Xiomara Castro fulfilled, it’s a symbolic gesture indicating to China that Honduras is open for business. With the United States’ superpower monopoly declining in some respects, Latin American countries now have to weigh the costs and benefits of gesturing towards China, and other superpowers broadly.

“The fact of the matter is that, today, China is indispensable to the region,” Cohen said.

The emerging lithium market represents just another variable that Latin American countries will have to take into account in making gestures and business deals with superpowers.

About Alfredo Eladio Moreno

Fredo is a journalist and photographer from his native Houston, Texas. He has reported since 2020 on Mexican politics and immigration policy in the United States, and especially on Nicaragua and the Ortega-Murillo regime. He is a graduate student of Journalism and Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University, where he is Editor-in-Chief of the Latin America News Dispatch.