Dispatches, Features, Mexico, North America

Canada’s Broken Pledge to Mexican Human Rights Defenders

July 30, 2019 By Staff

This story, written by Urooba Jamal and José Luis Granados Ceja, was originally published in NACLA.

After his father was murdered a decade ago over his opposition to a Canadian-owned barite mine, José Luis Abarca has been fighting relentlessly to secure justice. José Luis’s struggle has taken him from his rural community in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas all the way to the Federal Court of Canada in Ottawa, where he sought to hold Canadian officials accountable for their alleged role in his father’s murder. Last Tuesday, however, José Luis once again faced disappointment from the Canadian court system, as the Federal Court upheld a decision that determined that Canadian embassy officials were under no legal obligation to protect human rights defenders such as his father.

“We are totally disappointed with the ruling because we have walked a long road in search of justice over the murder of my father,” José Luis said in a statement.

Canada dominates global resource extraction. Sixty percent of mining companies in the world are headquartered in Canada, while 41 % of the large mining companies in Latin America are Canadian. The two have developed a symbiotic relationship: the Canadian state benefits from tax contributions from these companies while actively supporting mining companies’ business interests by providing diplomatic backing to their projects abroad. A landmark 2016 report by the Justice and Accountability Project (JCAP)—a partnership of two Canadian law schools that advocates on behalf of Indigenous communities affected by resource extraction—found that Canadian mining companies in Latin America contribute to violence and act with impunity. The first investigation of its kind, the report documented 44 deaths, 403 injuries and 709 cases of criminalization against peaceful protesters involving 28 Canadian companies in 13 Latin American countries over a 15-year period.

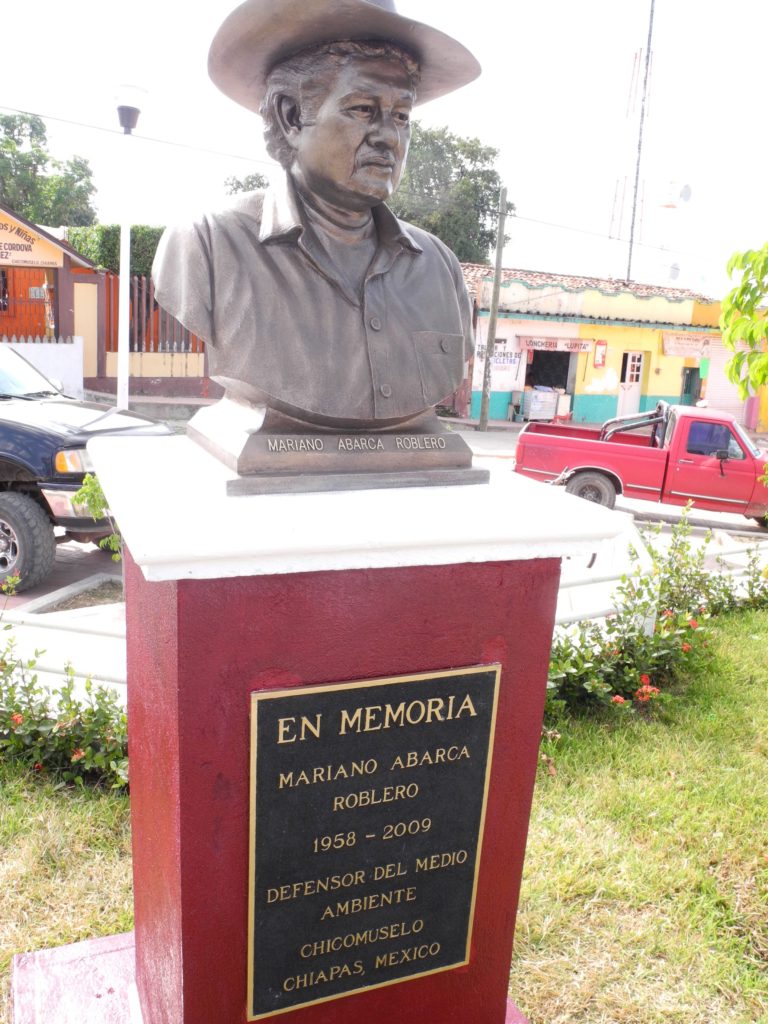

The murder of Mariano Abarca is drawing this relationship into question, highlighting the need for an independent Canadian watchdog, and exposing the lengths some Canadian politicians will go to protect mining companies—with human rights defenders often paying the price of this relationship. The recent decision against the Abarca family highlights how far the Canadian government still has to go in recognizing its own complicity in the violence perpetrated by Canadian mining companies.

According to José Luis, “It is important for us to let the people, communities, governments and countries where these mining companies are coming from know that these companies are coming to destroy our communities—they’re coming here to kill our people.”

The Murder of Mariano Abarca

Shortly after the barite mine—run by a Canadian company called Blackfire—began operating in his community of Chicomuselo, Chiapas, in 2008, Mariano Abarca began to lead protests. As one of the co-founders of the Mexican Network of People Affected by Mining (REMA), a network of organizations and grassroots movements that resists harmful mining projects, Mariano charged that Blackfire had failed to obtain consent from affected Indigenous communities, and also held serious concerns that toxic emissions from the mine would pollute local waterways. He soon received threats against his life from Blackfire employees as a result of his activism, according to a petition his wife and children filed to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). On Aug. 11, 2008, three workers from the mining company invaded Abarca’s home, held a pistol to his wife’s head and beat him and one of his sons.

Undeterred, Abarca led a protest the following summer that marched from his hometown to the Canadian embassy in Mexico City to challenge Canada’s complicity in the conflict the mine had created. He delivered a speech targeting an embassy worker, saying “thugs” from Blackfire had been harassing protesters. Shortly after, Blackfire filed a complaint against him, and on Aug. 17, 2009, masked men—who turned out to be Mexican police—arrested Abarca. While Abarca was detained for eight days, the Canadian embassy received over 1,400 letters of support from across Latin America and Canada from people concerned about his safety.

On November 23, 2009, Abarca filed his own complaint against Blackfire, alleging that two of its employees had made death threats against him. Just four days later, as Abarca sat in his truck outside his home with a friend, a gunman shot Abarca three times before escaping on a motorcycle.

Bust in memory of Mariano in his hometown of Chicomuselo, Chiapas. (Photo by Jennifer Moore)

Just days after Abarca was murdered, Mexican authorities from the state of Chiapas shut down the mine over a number of environmental concerns, including pollution and toxic emissions. Soon thereafter, activist groups claimed that Blackfire had bribed the mayor of Chicomuselo to quell anti-mining protests—accusations the company later denied.

Blackfire, which has since dissolved, denied involvement in Abarca’s murder, distancing itself from the three suspects—all Blackfire employees—arrested in relation to the assassination. Mexican authorities eventually freed Jorge Carlos Sepúlveda Calvo, the only one of the three to be convicted, after an appeals court found he was not afforded due process.

Canadian Complicity and Impunity

In 2013, Mining Watch—a Canadian watchdog organization—filed a freedom of information request. As a result, the Canadian government released more than 900 documents, some redacted, revealing the details surrounding Abarca’s murder and the extent of the collusion between the Canadian embassy and Blackfire.

The Canadian newspaper The Star first reported on these findings, including one email sent from a Blackfire executive to the embassy in September 2008, which thanked officials there for “everything they did to pressure the state government to get things going for us.” The email ended saying, “We could not…[have started the mine in Chiapas] without your help.”

José Luis Abarca said that he felt confident that the Canadian embassy was aware of the threats his father faced and that if staff at the embassy would have acted differently, his father would not have been murdered. But instead, he said, embassy staff “put the interests of the mining company above human lives.”

In February 2018, the Justice and Accountability Project (JCAP) took up Abarca’s case and filed a complaint with the Canadian Public Sector Integrity Commissioner (PSIC), Joe Friday. They alleged Canadian embassy officials in Mexico had breached a number of policies in relation to Abarca’s murder and demanded an investigation into the lack of action by Canadian officials in preventing Mariano’s death.

Shin Imai, legal counsel to the Abarca family and the director of JCAP, said that embassy officials failed to meet their obligations under the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act, which requires Canadian public servants to support human rights defenders.

“The Canadian embassy ignored warnings that Mr. Abarca’s life and safety were in danger, while actively advocating on the company’s behalf with the government of the State of Chiapas,” reads the complaint.

Edith Lachapelle, the communications manager for the PSIC’s office, told the Canadian newspaper Now Toronto last year, “To date, there has never been a finding of wrongdoing committed by anyone working for a Canadian embassy investigated by the [Public Sector Integrity] Commissioner’s office.”

According to Kirsten Francescone, Mining Watch’s Latin America director, representatives from Global Affairs Canada, the government’s foreign affairs department, have explicitly stated in meetings with Mining Watch that the Canadian government has a diplomatic role in promoting Canadian mining interests abroad.

“All of the facts clearly showed that the embassy acted in particular ways that increased the threat on Mariano’s life and that ultimately led to his assassination,” Francescone said.

Imai was skeptical of the government’s absolution of its responsibility. “We’re not saying that the Canadian embassy ordered the assassination of Abarca,” he explained. “What we’re saying is, because of the danger of human rights defenders, embassies have policies that are supposed to reduce the risk.”

One of those policies indicates the embassy’s role in facilitating “open and informed dialogue between all parties,” something the Canadian ambassador failed to do, Imai said. “He never talked to Mariano Abarca, he never talked to the community. He didn’t try to facilitate an open dialogue. He actually went and demanded that the government of Chiapas do something to protect the Canadian company, to facilitate the business of the Canadian company.”

PSIC Commissioner Joe Friday ultimately rejected the group’s arguments, stating Canada’s policies related to corporate social responsibility were not “official”—that is, not binding—and therefore the complaint was not in the public interest to investigate.

Although the Abarca family fought the decision, the Federal Court upheld the commissioner’s ruling last Tuesday.

“This decision crudely shows that there was very little willingness on the part of the judge to study and analyze the evidence in depth since he did not consider the arguments we presented,” one lawyer representing the Abarca family, Miguel Angel de los Santos, said in a statement.

In the judgement issued by the Canadian Federal Court, Judge Keith Boswell admitted that “perhaps Mr. Abarca would not had been murdered” had the Canadian embassy acted differently, despite ruling against the Abarca family.

Beyond Abarca

Human rights advocates have cited the murder of Mariano Abarca—in particular, the behavior of the mining company, the allegations of corruption, and the role played by Canadian embassy staff surrounding the event—as an example of why Canada needs an investigatory watchdog with a clear mandate and the necessary powers to investigate allegations of misconduct by Canadian companies abroad.

In response to these demands, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau agreed in January 2018 to put in place a corporate-ethics ombudsperson, named the Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise (CORE).

However, when the government finally established the office in April, the Liberal government seemingly backtracked on a key element: the new CORE would not hold investigative and enforcement powers.

Imai said lobbying records revealed a “powerful” and persistent lobbying campaign on behalf of the mining industry to secure “an ombudsperson [without] powers.”

According to an internal memo sent by Imai and his colleague Charlotte Connolly at JCAP, mining industry officials—namely, the Mining Association of Canada (MAC) and Prospector & Developers Association of Canada (PDAC)—made over 500 contacts with high-level government officials in the 16-month period between January 2018 and April 2019, with 100 specific to international issues. Many of these officials included those from the Prime Minister’s Office, Global Affairs Canada (specifically the Minister’s Office of International Trade Diversification), and Natural Resources Canada.

The Minister’s Office of International Trade Diversification did not reply to a request for comment.

On the campaign trail, Trudeau’s Liberal party promised CORE would provide a needed replacement to former prime minister Stephen Harper’s Corporate Social Responsibility Counsellor, widely regarded as toothless by civil society organizations—but Imai argues it is much the same.

“It was going to be an avenue for getting some truth about these conflicts,” he said, referring to the countless cases beyond Blackfire that implicate Canadian mining companies in human rights scandals abroad. “The way it is right now, it is more of a tool to cover up wrongdoing by mining companies and to promote mining, not to investigate reports of wrongdoing.”

“The [mining] industry must be very, very pleased,” he added. “Now they have a government-paid employee who’s going to promote [them].”

Mining Watch maintains that in order to be effective, CORE must have the power to compel witnesses, the tools and staff to conduct proper investigations, and, crucially, independence from government.

A Broken Promise

José Luis Abarca also expressed profound disappointment with the Trudeau government’s betrayal.

“We, the human rights defenders—those who defend the environment—we are left totally unprotected,” he said.

José Luis explained that in countries like Mexico, which is plagued with rampant corruption, it is nearly impossible to achieve justice. Therefore, human rights defenders must have other avenues to pursue it.

José Luis Abarca. (Photo by José Luis Granados Ceja)

Mexico’s new leftist president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has emphasized the fight against corruption, framing it as the key problem plaguing the country. Still, José Luis doubts that the Mexican president will be able to tackle the problem.

He also fears that the ongoing lack of accountability from Canada will lead to abuses elsewhere. For the Abarca family, he explained, this fight is not just about obtaining justice for Mariano, but to establish a precedent so that other land defenders and human rights defenders worldwide are not putting their lives in danger.

The threat Canadian mining companies pose is not limited to the Western hemisphere. A recent briefing document prepared by the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, which analyzed the impact of 10 Canadian mining companies in places such as Tanzania and the Philippines, concluded that “Canadian mining companies display a depraved indifference to human life.”

That indifference cost Mariano Abarca his life. Meanwhile, his family continues to face danger.

“I got really deep, deep, deep respect for [the Abarca family’s] courage in continuing to do this, because the person they suspect killed Mariana Abarca is just walking around town,” Imai said.

Despite the recent ruling by the Federal Court, the Abarca family has pledged to continue their fight for justice.

“To not investigate the embassy of Canada is to fear knowing the truth concerning the way that mining companies operate in Latin America, and above all, in Mexico and Chiapas where Canadian officials help facilitate the operations of Canadian mining companies that have caused severe ecological damage and human rights violations,” Uriel Abarca Roblero, Mariano’s brother, said in a statement. “Despite the ruling, we will not give up and we are going to continue in this fight for justice.”

After 10 years, with the decision by the Canadian court enabling impunity, the Abarca family remains committed not only to securing justice for Mariano, but to ensuring that no other human rights defenders and their families will have to face what they have endured.

Urooba Jamal is a Canadian freelance journalist who writes about global social and political issues. She formerly worked at teleSUR English, reporting on Latin American issues and politics from Quito, Ecuador. In September 2019, she will pursue a Master’s degree in Journalism, Media and Globalization in Europe as an Erasmus Mundus scholar. You can follow her on Twitter at @uroobajamal.

José Luis Granados Ceja is a journalist and photographer based in Mexico City. His work is primarily focused on contemporary political issues in Latin America and often looks at the efforts of social movements and labor unions to affect change. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram at @GranadosCeja.