Features, Uruguay

FEATURE: Burying the Past? Former Uruguayan Prison Becomes Shopping Mall

December 21, 2009 By Mari Hayman

MONTEVIDEO, Uruguay — Serrana Auliso is eighty years old, but moves with the fierce agility of a woman half her age. I’ve scarcely passed the threshold of her front door when she leads me by the hand into the living room, upends a heavy sofa and drags a side table across the floor.

“Help me move the rug,” she instructs.

We roll back Auliso’s faded carpet to reveal nine discolored stone tiles on her living room floor, composing a two-by-two foot square faintly darker than all the surrounding tiles. I stare at the outline on the floor.

“It was an abuse,” she declares.

In Spanish, the term abuso falls somewhere between “mockery” and “outrage.” For a certain generation of Uruguayans, it is a word that has passed into national lore: “El Abuso” is the code name of a 1971 prison break that led 106 members of the Tupamaros, an urban guerrilla movement, to emerge from the hole I am staring at in Auliso’s living room floor. Self-styled revolutionaries with a knack for publicity, the Tupamaros were already notorious for Robin Hood-esque economic redistribution stunts when their escape from Punta Carretas Prison landed them in the Guinness Book of World Records.

Today, the imposing gray walls of the former prison – just across the street – still block the light in Auliso’s living room. Sitting in her red upholstered chair, the gray-haired former English teacher tells me what happened in the years after the Tupamaros’ escape in her clear schoolteacher’s voice. Most of the escaped guerrillas were re-apprehended during the following twelve years of military rule, a time in which kidnappings and torture were commonplace and Uruguay had the highest per-capita rate of political incarceration anywhere in the world. Just five years after the dictatorship ended in 1985, the prison was transformed into a symbol of a new, democratic Uruguay: the Punta Carretas Shopping Center, Montevideo’s most upscale mall.

According to a 2007 article in the industry magazine Shopping Centers Today, Punta Carretas Shopping Center “is doing a much better job of keeping shoppers in than it had with prisoners.” The mall currently has 180 shops, five anchor stores, a 700-seat food court and a 10-screen cinema. Thanks to the mall, the neighborhood of Punta Carretas has emerged from the shadows to become one of Montevideo’s most elegant residential districts, where the 26-story Sheraton Hotel towers over tasteful single-family homes and fashionable stores, restaurants and bars.

But no trace of the Tupamaros’ tunnel to freedom can be found in the mall, or specifically in the ground-level stationary store that used to be a cell for “common” prisoners (five of whom escaped with their guerrilla colleagues). The former prison administration building now houses a McDonald’s and a Don Pepperone restaurant with patio seating, and during the holidays, an enormous Christmas tree blinks at the foot of the mall’s grand staircase under a free-standing arcade that once led into the cell blocks. Older shoppers with Uruguayan wool sweaters draped over their shoulders linger outside the “Manos de Uruguay” store, appraising the silver-plated mate gourds with discernment, and teens in matching Adidas sneakers file into Zara and Urban Outfitters. Really, it’s like a mall anywhere – aesthetically enhanced by its historic elements but purged of the uncomfortable essence of its past.

Mario J. Garbarino, the developer of Punta Carretas Shopping Center, is in the midst of an ambitious expansion plan for the mall over the next several years – more commercial space, a new health spa, even a high-rise apartment building to rival the towering Sheraton (which he also developed). Garbarino was the original mastermind behind the prison’s transformation into a shopping mall. Due to a scandal involving the sale of the prison by Uruguay’s former Minister of the Interior (who now sits on the mall’s administrative board), the process was probably far more politically controversial than Garbarino had anticipated. After a public bidding process that discarded several other less financially feasible options – like turning the complex into an athletic facility – he began the four-year construction on the mall in 1990.

Mario J. Garbarino, the developer of Punta Carretas Shopping Center, is in the midst of an ambitious expansion plan for the mall over the next several years – more commercial space, a new health spa, even a high-rise apartment building to rival the towering Sheraton (which he also developed). Garbarino was the original mastermind behind the prison’s transformation into a shopping mall. Due to a scandal involving the sale of the prison by Uruguay’s former Minister of the Interior (who now sits on the mall’s administrative board), the process was probably far more politically controversial than Garbarino had anticipated. After a public bidding process that discarded several other less financially feasible options – like turning the complex into an athletic facility – he began the four-year construction on the mall in 1990.

Garbarino received me in his office at Punta Carretas Shopping Mall and was eager to share his plans for the mall’s expansion. Spreading the blueprints on his desk, he proudly explained how the riverfront skyline of Punta Carretas will be further transformed in the next five years: a fourteen-story office building, high-rise apartments, 32 new stores and space for a new supermarket. This is the future Uruguay: another world entirely from the enlarged black-and-white image of the prison that hangs prominently in Garbarino’s boardroom.

“We prefer not to identify ourselves with the prison, although we did maintain some of its architectural elements,” Garbarino says, explaining why this grainy photo of Punta Carretas under military rule was not displayed in the mall itself. “Our idea has always been to associate the mall with freedom and traditional values. We have turned a prison into a space of complete freedom.”

Though the mall won an international award in 1996 for incorporating elements of the prison’s original architecture into its design, not even a plaque commemorates the building’s history. Maren Ulriksen, a prominent Chilean psychoanalyst and cultural critic who has lived down the street from Punta Carretas Shopping for nearly 30 years, finds this deeply troubling. Ulriksen and her husband Marcelo Viñar have spent decades rehabilitating the children of political prisoners, and it was she who first showed me a snapshot of the Christmas tree in Punta Carretas and a clipping of a Wella shampoo ad that implored tangled hair to “torture no more.” Yes, “Nunca más”, the rallying cry of the families of the disappeared in Latin America, is now being used to market shampoo.

Ulriksen’s memories of the former prison are vivid. She remembers watching the guards patrol the prison walls from her upstairs window, and hearing the Tupamaros’ footsteps the morning they escaped. Nor can she forget the flood of rats unleashed on the streets of Punta Carretas the day the old cell blocks were finally dynamited to make room for the mall. “The rats were so numerous that I could hear them. They were fleeing the destruction,” Ulriksen remembers.

Ulriksen’s memories of the former prison are vivid. She remembers watching the guards patrol the prison walls from her upstairs window, and hearing the Tupamaros’ footsteps the morning they escaped. Nor can she forget the flood of rats unleashed on the streets of Punta Carretas the day the old cell blocks were finally dynamited to make room for the mall. “The rats were so numerous that I could hear them. They were fleeing the destruction,” Ulriksen remembers.

“After the razing of the prison and the construction of the mall, there has been a political effort to erase the past, to create this perversion of memory,” Ulriksen says. “What kind of democracy have we recuperated if there’s no memory left to reclaim?”

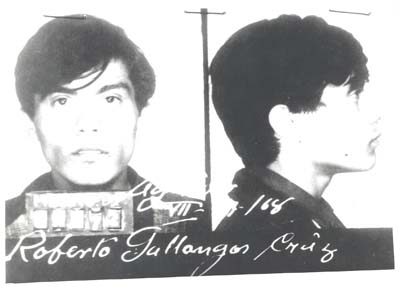

Uruguayan human rights groups have echoed Ulriksen’s concerns about their country’s historical amnesia for years, particularly in light of the recent failed national referendum that would have finally permitted trials for dictatorship-era human rights abuses. Nonetheless, Uruguayan political reality is proof that the traumatic past isn’t so easily buried. There is now a monument to the disappeared in Montevideo, a memory museum, and some discussion of the dictatorship in secondary schools. Several of the guerrillas who tunneled through Serrana Auliso’s living room floor now occupy important positions in Uruguay’s left-leaning Frente Amplio government. One of them, José “Pepe” Mujica, won last month’s presidential election and will be inaugurated in March.

Meanwhile, most Uruguayans I speak to recognize that the Punta Carretas Shopping is here to stay, regardless of their memories of the dictatorship or their concern that the mall erases the past. Even Ulriksen admits that she goes to the mall to buy groceries – she lives two blocks away, and it’s convenient. “I feel guilty, but it’s right across the street,” she says.

At the mall, people are generally pleased with the transformation of Punta Carretas from a gray prison neighborhood into one of the trendiest zones of the city. “They turned an ugly thing into something beautiful,” says Ivonne Aguilera, 27, a native of Paraguay now working in the mall’s food court. “It’s really extraordinary and impressive.”

“I think it’s fabulous,” concurs Susana, 63, an architect who lives nearby and feels that any recognition of the site’s history is unnecessary. “Precisely because it was a jail, it’s something that’s better not to remember.”

But her friend, Rosa, 68 and also an architect, does not agree. “But not to know?” she asks Susana. “It’s history! It’s like one of those American movies about jailbreaks. The prisoners were intelligent, you know, they were university students.”

Like the general public, Punta Carretas Prison’s former inmates and their families have diverging views about how and whether to remember their time there – for most, it was only a precursor to the horrors of their next decade and a half of incarceration, hard labor, and physical and psychological abuse. Most of Uruguay’s former political prisoners survived the dictatorship, but they bear the scars of their imprisonment to this day.

“Isn’t it preferable that such a central part of the city should house a shopping center and not a prison?” asks Tabaré Rivero Cedrés, a former Tupamaro guerrilla who escaped twice from Punta Carretas (once through the tunnel, once through the sewer system) and spent the next twelve years at the high-security Libertad Prison. “I’m not curious about it. It doesn’t interest me.”

Rivero, who decades later still retains the fiery look of a blue-eyed, wild-haired revolutionary zealot, now lives on the outskirts of Montevideo in a small and modest house that he built with his companion, Marilyn. Between sips of mate, he gruffly tells me that he has little interest in visiting the Punta Carretas Shopping Center – or any mall, for that matter – and even less desire to revisit the past.

“What kind of memories are we supposed to preserve? Make all of Uruguay into a memorial?” Rivero asks me, an edge to his voice.

Micaela, Rivero’s daughter, was born in prison in 1970 and admits that she and her father rarely see eye-to-eye. “I feel a need to testify, to find some meaning in this,” says Micaela, who spent her childhood visiting both parents in prison while she was shuttled back and forth between relatives. “I’m almost forty years old now and I still can’t even begin to write about my family’s experiences,” she says. “In this country it’s impossible to recover from something, because they never give you a chance.”

Rivero says he supports his daughter’s participation in Memoria en Libertad, a group organized by the children of Uruguayan political prisoners, but he has forsworn political activism himself. “They tortured me, and it’s not the same way they tortured her. It affected her one way and me another. It doesn’t hurt me; it doesn’t bother me in the least. It was another time and place.”

Unlike former comrades who have braved mobs of shopping teenagers to find their old prison cells at Punta Carretas, Rivero has never returned.

“At least back then, we had the sense to break out of there. Now people go of their own volition,” he says.

Image 1 (jcmally @ Flickr): Entrance to Punta Carretas Shopping Center

Image 2 (Mari Hayman): Publicity for the expansion plan for Punta Carretas Shopping Center

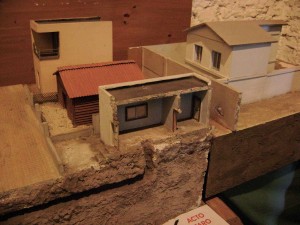

Image 3 (Mari Hayman): Model of Punta Carretas prison and the escape tunnel the Tupamaros dug across the street into Serrana Auliso’s living room in 1971, Casa Tupamaros in Montevideo

5 Comments

Great story!! And great website, congratulations!

I second that. Great article. Great voices on an important issue. It shows how volatile memory becomes the further we move away from the events. It’s also fascinating who wishes to remember and who wishes to forget. Great work.

Great job, Mari and great site. Congratulation to all involved. You make NYU proud.

I think your blog is fantastic I found it on Yahoo. Definetely will return again! I am very exsiting about learning newstuffBest Regards, Glen

This info is worth everyone’s attention. When can I find out more?

Comments are closed.