Dispatches, United States, Uruguay

Nixon Administration Advocated Use of Death Squads in Uruguay, New Documents Indicate

August 17, 2010 By Mari Hayman

The U.S. Embassy in Montevideo after its inauguration in 1969.

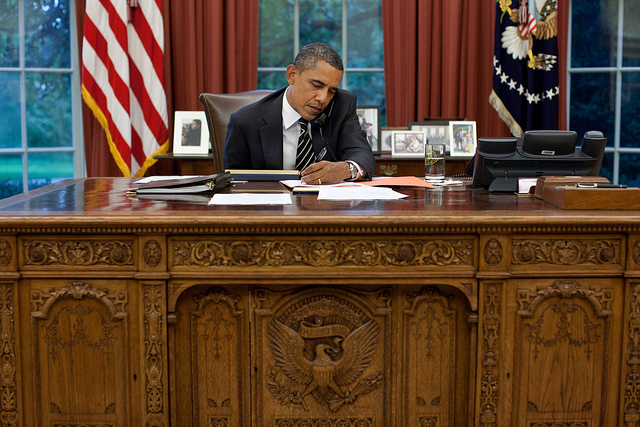

NEW YORK — Forty years after U.S. AID official Dan Mitrione was kidnapped and executed by Uruguayan guerillas, nine declassified State Department documents prove that high-level officials in the Nixon Administration advocated the use of death threats against Uruguayan guerrillas, political dissidents, and their families.

The Washington-based National Security Archive released the documents last Wednesday on the anniversary of Mitrione’s August 10, 1970 death, when the former U.S. AID official’s body was found shot at close range after ten days in captivity. Mitrione’s death escalated the Uruguayan government’s campaign against the MLN-Tupamaros and other leftist guerilla organizations as well as students, union leaders, and political opposition, eventually leading to the country’s 1973 civil-military coup and twelve years of dictatorship.

According to Carlos Osorio, director of the National Security Archive’s Southern Cone project, “The documents reveal the U.S. went to the edge of ethics in an effort to save Mitrione—an aspect of the case that remained hidden in secret documents for years.”

Mitrione, a former police officer, arrived in Uruguay in 1969 to provide logistical and technical support to the Uruguayan police as director of the U.S Agency for International Development’s Office of Public Safety. Suspecting Mitrione of training security forces to torture detainees during the government’s aggressive counter-insurgency campaign, the Tupamaros kidnapped him on July 31, 1970, and demanded the release of 150 political prisoners in return for his life — a demand that was immediately rebuffed by then-president Jorge Pacheco. Mitrione was found dead ten days later.

The written communications between former U.S. Secretary of State William Rodgers and former U.S. Ambassador Charles Adair are the earliest recorded acknowledgment of death squads in Uruguay by U.S. government officials, although the National Security Archive says more research is needed to determine the full extent of the U.S. government’s involvement in Uruguay’s state security operations prior to the dictatorship.

One of the nine cables shows that while the U.S. was under pressure to save Mitrione after the Tupamaros set a deadline to execute him, former U.S. Secretary of State William Rodgers wrote that he “assumed that the Government of Uruguay has considered use of threat to kill (Tupamaros leader Raúl) Sendic and other key MLN prisoners if Mitrione is killed.” According to the August 9 cable, Rodgers told then-Ambassador Charles Adair that “If this has not been considered, you should raise it with GOU [Government of Uruguay] at once.”

Later that day, Adair cabled back to Secretary Rodgers with the Uruguayan Foreign Minister’s reply that “his type of government did not permit such action.” However, Adair added that “he [the Foreign Minister] understood that through indirect means, a threat was made to these prisoners that members of the ‘Escuadrón de Muerte’ (Death Squad) would take action against the prisoners’ relatives if Mitrione were killed.”

“The U.S. documents are irrefutable proof that the death squads were a policy of the Uruguayan government, and will serve as key evidence in the death squads cases open now in Uruguay’s courts,” said Clara Aldrighi, a professor at Uruguay’s Universidad de la Republica who collaborated with the National Security Archive on its two-year research project. “It is a shame that the U.S. documents are writing Uruguayan history. There should be declassification in Uruguay as well,” she said.

Nine declassified State Department cables relating to the Mitrione case can be seen in their entirety on the National Security Archive website. According to Amnesty International, at least 134 Uruguayans were disappeared and thousands detained and tortured in the period between 1973 and 1985.

Image: U.S. Embassy Montevideo @ Flickr.