Central America, Dispatches, United States

Reunification with Family in US is Bittersweet for Child Migrants

April 19, 2016 By Katie Schlechter

This article was originally published in Civic Ideas on April 18, 2016.

NEW YORK — It is an uplifting image: a child seeing her mother for the first time after more than a decade apart. But for tens of thousands of young migrants who arrived in the United States from Central America during the past two years, reunions with family are often bittersweet.

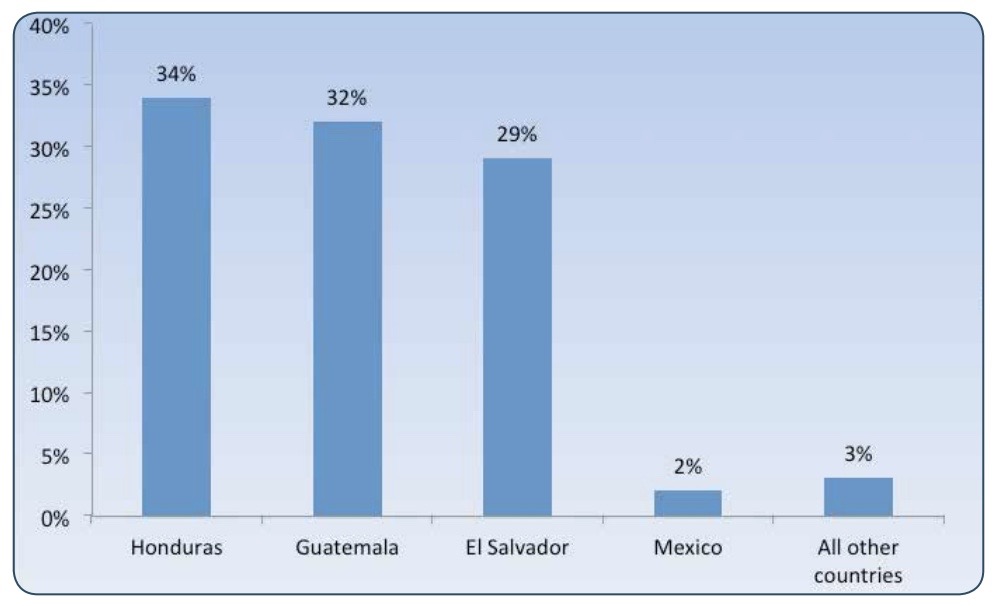

Since October 2015, the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement has released 22,798 unaccompanied child migrants to sponsors across the country, according to ORR’s latest numbers; it also had released 53,515 and 27,250 in the two prior fiscal years. Two-thirds are boys and most are between 14 and 18 years old. Ninety-five percent of them traveled from El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala.

Over half were resettled with a parent already living in the United States to await deportation hearings. Though initial reunions between family members are usually joyful, the reality of reestablishing a relationship is challenging.

“The first month is all full of, ‘We’re finally together.’ There’s tears, there’s joy, there’s ‘Let me show you the city,'” said Cristina Muñiz de la Peña, mental health director and co-founder of Terra Firma, a medical-legal partnership that works with unaccompanied child migrants in New York. “And then the stressors, the reality hits.”

Most of the resettled young migrants are teenagers. They are coping with adolescence, navigating a new relationship with their parent and facing legal and other pressures.

“They’re in deportation proceedings, first of all, but not only that, it’s about coming from rural Guatemala to the South Bronx, or coming from San Pedro de Sula to Arizona,” said Brett Stark, another co-founder of Terra Firma who serves as the project’s legal director. “Whatever those transitions and adjustments require, acclimating to that can sometimes compound trauma that kids have already been through.”

Countries of origin for unaccompanied child migrants placed into ORR custody from October 2013 through September 2014. Ninety-five percent of these young migrants came from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras. (Image: ORR Annual Report to Congress, FY 2014)

Violence by gangs and by police, as well as desire to reunite with family in the United States, has been driving large numbers of minors to flee their home countries since 2013. Homicide rates in El Salvador and Honduras are 15 times that of the United States. Children and teenagers there are frequent targets of gang recruitment and “mano dura” (heavy handed) police tactics adopted to crack down on suspected gang activity.

Unaccompanied minors from countries that do not border the United States are protected from immediate deportation by a 2008 anti-human trafficking law. Under this law, the Department of Homeland Security must turn these youth over to ORR within the Department of Health and Human Services so that it can start the process of placing them with qualified sponsors named by the young migrants, with foster families or in approved housing facilities.

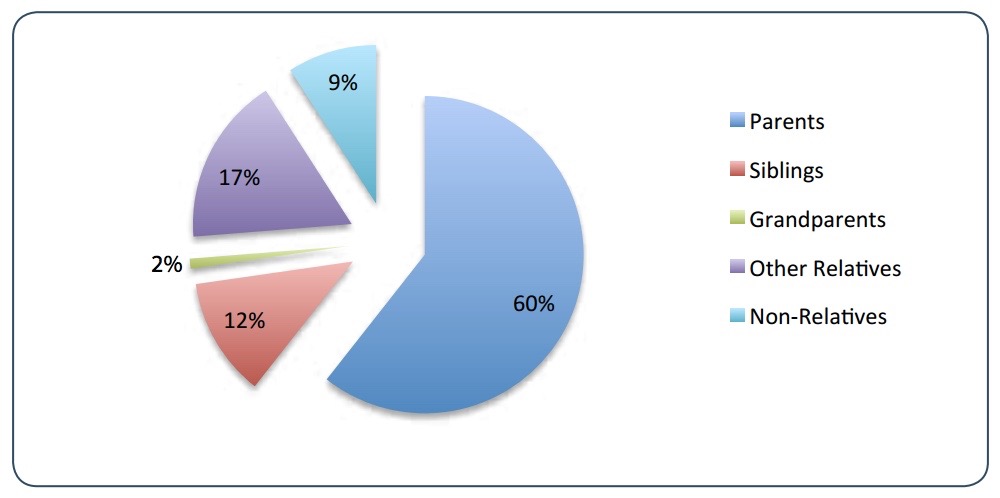

Sponsors are entrusted with providing for the children, enrolling them in school and ensuring that they attend their immigration hearings. ORR reported to Congress in 2014 that from October 2013 through September 2014, biological parents made up 60 percent of sponsors.

Parents and family members cannot simply pick up children upon their arrival. In an effort to protect unaccompanied migrants from being released to unfit caregivers or into human trafficking situations, ORR vets sponsors with background checks, interviews and home visits.

Despite these efforts, the ORR came under fire during a Senate hearing in January for mistakenly releasing a number of migrant children to human traffickers. The Senate investigation found 34 cases that contained some indications of human trafficking, but an investigation by The Associated Press suggests that the number could be higher.

The report from the hearing accused the agency of failing to adequately vet sponsors during the sponsor placement process. It also criticized the ORR policy of closing cases and not following up on sponsor placements with home visits unless the child migrant is considered especially vulnerable.

For the 10 percent of cases in which ORR conducts home visits and post-reunification monitoring, the agency contracts local organizations to do this work. Letticia Batista is a case manager at Catholic Charities in New York, one of the organizations contracted by the ORR to vet sponsors and assist with reunification. After sponsors pass through the initial application process, Catholic Charities sends Batista to meet them and try to ensure that their homes will be safe environments for children.

Many sponsors are undocumented immigrants, which can make them fearful of the sponsorship application process. Batista said that she often has to explain to potential sponsors that she does not work with immigration officials. “They just fear everyone,” she said. “Like they’re gonna get deported for everything, and that’s not the case.”

The application process can take several months. Young migrants spend this time in ORR shelters where they attend school and have access to healthcare.

Sponsor relationship to unaccompanied child migrants released to their care by ORR from October 2013 through September 2014. More than half of sponsors a biological parent of the young migrant (Image: ORR Annual Report to Congress, FY 2014)

Once sponsors are approved and children arrive in their new homes, they face new challenges. When the sponsor is the young migrant’s mother or father, both parties tend to come into the reunification process with certain expectations about the relationship. Katie Kuennen, the assistant director of family reunification with the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in Washington, D.C., said that children’s hopes for their new lives with mom or dad don’t always pan out.

“They have this fantasy that they’re going to be reunified with their parent after so many years and everything’s going to be great and wonderful,” she said. “And the reality is, mom’s working two or three jobs, she’s never home, they don’t have that time to reconnect as perhaps was envisioned.”

Young migrants often struggle with feelings of abandonment after a long separation. Kuennen said that even if parents maintained contact from afar, children still need to accept their parents’ decision to have left them behind in the home country.

Likewise, parents have to make the leap from caring for a young child to parenting an adolescent. “We’ll have a parent, for example, who left El Salvador when the child was 4 or 5 years old, and now they’re reunifying with a teenager,” said Kuennen. “But they have the remembrance of their child as that much younger child, and the parenting skills are just very different.”

Living with mom or dad again is also a big adjustment for unaccompanied migrants. “Oftentimes these kids have had to grow up very quickly and be responsible for many things at a young age,” said Kuennen.

Many young migrants saw or suffered horrific violence in their home countries or on the journey to the United States. “These are kids who have been kidnapped or they’ve witnessed other kids being beheaded,” said Kuennen. “Or they’ve been held for ransom by the gangs while they were journeying here or back in the home country, or they witnessed their best friend get killed.”

This year, the American Psychological Association reported that it is not uncommon for young migrants to arrive with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety or other conditions.

Batista said that in her work for Catholic Charities she’s seen some parents struggle to understand what their children experienced, and children who avoid revealing their ordeals, “because a lot of times they’re afraid to tell their moms what happened. They’re protecting them.”

She said that working toward child and parent being able to talk openly about what happened helps the child to heal and strengthens their relationship. Some parents are better prepared for this than others. “You’ll have a very proactive mother that’s very aware of the trauma and the help she’s gonna need to help heal this child,” said Batista. Even in these circumstances, young migrants need outside support systems.

Muñiz de la Peña says that the more difficult cases involve families who did not initially have access to services in their communities. Terra Firma is working to fulfill the needs of young migrants and their families during this transition period. As a project of Catholic Charities, The Children’s Health Fund and The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, it provides legal counsel, medical services and therapy to youth and their families.

Muñiz de la Peña works with youth individually as well as together with their parents. Family sessions foster stronger connections between children and sponsors, she said, adding that in her sessions with the young migrants, she helps them “understand that what they’ve been through creates wounds and also creates resilience.”

Batista helps parents understand the importance of getting their children into therapy. “It’s not just physically having the child there; it’s making sure the child is flourishing and growing and overcoming some of their past,” she said. She connects families to services and youth programs in their communities and checks on them every few months, in person and by phone, until the child turns 18.

In family sessions, Muñiz de la Peña encourages parents and children to talk to each other about what they aren’t discussing at home. Using a tactic calls “circular questioning,” she might ask a mother to share her perception of her child’s experience. “Then the child hears mom and sees, ‘Oh, Mom knows more than I thought or understands more’—or not,” she said. “Then you have to raise that awareness and say, ‘It seems like you feel that she doesn’t fully get it. Why don’t you tell her?'” She said that this helps families build a more solid foundation together.

Yet some barriers to a smooth reunification process are beyond the control of young migrants and their families. They often face housing problems, lack of legal representation for the children’s immigration cases and the general fear that comes with being undocumented.

Muñiz de la Peña said that some parents, fearing the discovery of their own immigration status, are overprotective. “They don’t let them go out. They’re scared of getting connected anywhere and people knowing about their status,” she said, and this can lead to tension at home.

Stable housing is another issue that weighs heavily on reunifying families. With New York rents rising and few apartments available for undocumented individuals, many families lose their homes.

“When a family comes and tells me, ‘We’re about to be evicted,’ I feel sometimes at a loss,” said Muñiz de la Peña. There are very limited services to help families in this situation, she said. In addition to causing stress, a change of address also complicates young migrants’ immigration cases. When the court doesn’t know where to find children to remind them of their next hearings, they are in danger of failing to show up and judges could order them deported “in absentia.”

With the support of projects like Terra Firma and community organizations, however, migrant children and teens can get help to overcome many barriers to successful reunification.

“Most of the time, it’s a success story,” said Batista. “Most of the time, the mother is so happy with the child and the child is happy to be here with the mom.”

About Katie Schlechter

Katie Schlechter is a journalist based New York City and a Henry MacCracken Fellow at New York University. After a long-term internship at Democracy Now, she worked as editor in chief of IndyKids, a nationally-distributed print and online newspaper written for and by children. She speaks Spanish and French and has studied and worked in Chile, Spain, France and Ireland.