Andes, Colombia, Dispatches, Features

Paramilitary Offensives Persist in Antioquia, Colombia

March 30, 2020 By Nicolas Bedoya

ITUANGO, Colombia– “When I was in the FARC-EP, I would see displaced people,” Wilmer said, drinking coffee in a cafeteria near an improvised refugee shelter.

“I would have to go to rural areas and the people would tell me that they had to leave their homes and I wouldn’t feel anything.”

Wilmer, 25, was one of 872 refugees who fled fighting between armed groups on February 23, near Ituango, Antioquia, in northern Colombia. LAND has changed his name for security reasons.

“When you experience displacement, you see how hard it is for yourself and everyone else,” he said.

A negotiated peace agreement in 2016 ended the 52-year armed conflict between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Colombian state. FARC militants agreed to reintegrate into civilian life. Wilmer is one of them. He reintegrated into a rural hamlet called El Cedral.

Ituango’s mayor provided the municipal gymnasium to shelter 325 people displaced from the rural sector of El Cedral, the largest of the 12 displaced communities. The other more sparsely populated communities were packed tightly in a small school just outside of town.

Three years after the FARC disarmed to the United Nations, the Colombian government is still unable to establish a presence in much of the remote countryside. Many regions that experienced relative calm under FARC hegemony are now a battleground between various armed groups struggling for control.

Caught in the middle of the war are former FARC combatants and social leaders. Since the signing of the peace accord, over 191 disarmed FARC and 323 social leaders have been assassinated nationwide. In Ituango alone, 12 former guerrillas and seven social leaders have been killed.

El Cedral community meeting after arriving to their improvised shelter (Pablo Cuellar/ VELA Collective)

Displaced communities seek refuge in Ituango

Wilmer is no stranger to hardship. His mother died of a sickness in Colombia’s neglected Pacific coast. His father was macheted to death. Wilmer ran away from a Medellín orphanage when he was 12. He walked over 100 miles to the coca fields bordering Ituango’s lowlands, one of the few places an underage child could get work. That’s where Wilmer met FARC guerrillas and asked to join them, when he was just 15. Even though he was a veteran foot soldier, Wilmer had never been forcefully displaced until now.

“We are here because of an order an armed group made yesterday morning telling us that we had to leave for our own safety,” said Jorge, a leader of El Cedral. LAND has changed his name for security reasons. “No one was allowed to stay. They said that they wouldn’t promise the safety of anyone who stayed.”

The order came from FARC dissidents who were expecting a paramilitary assault from neighboring Peque to the south. The armed group preemptively ordered the displacement to safeguard the community from their preferred method of war in this region, antipersonnel mines.

Most of the refugees were children and women. Many had little choice but to sleep on the cold concrete floors of the open-air gymnasium with just one blanket to share among an entire family.

Only eight of the refugees were ex-combatants of the FARC’s former 18th Front. Either they had family in the area or had married women in the local communities, like Wilmer.

The 18th Front controlled the region up until the peace deal, when 278 fighters disarmed in the UN-monitored Santa Lucia transitory zone in the mountain canyon neighboring El Cedral. Wilmer and several other ex-combatants moved to neighboring rural hamlets after handing over their weapons.

“No one slept the first night [after being displaced]. The dogs wouldn’t stop barking and crying,” said Jorge. “We aren’t used to sleeping like this, with all the noise. I’m used to sleeping in the mountains where the nights are quiet.”

“What most worries us are the animals we left behind. Mules, chickens, ducks, dogs, pigs,” said Yarcelly, Wilmer’s wife. “All we could do was leave as much feed on the ground as we had and let them loose to search for food themselves.”

Many of the poor farmers are already registered victims of the armed conflict due to a paramilitary offensive that burned their village in 2000. Their animals and land are the only form of capital they have.

Jorge, Wilmer, Yarcelly and hundreds of other farmers spent three nights away from their farms. Local authorities, typically slow to react, were able to provide food to the displaced. They returned home, but the risk of violence remains. In the month since the displacement, the army deactivated four mines in the area.

El Cedral rural hamlet (Nicolas Bedoya/ VELA Collective)

Paramilitaries flood “gateway” region

In January, the human rights ombudsman’s office in Colombia released an Early Warning System (SAT) report on Ituango. The reports alert other government institutions of “the likely occurrence of massive violations of human rights and international law.”

According to the report, armed groups have contested Ituango since the 1980s for being considered the “gateway” to the Nudo del Paramillo region.

The Nudo del Paramillo is a series of mountain valleys with dense jungle where the Andes mountain chain begins. An illegal drug and arms smuggling route runs through the region, circumventing government-controlled roads and connecting the Caribbean and Pacific Coasts with the coca producing region of Bajo Cauca.

The war in the region reached its peak in the 1990s and early 2000s, when several massive government and paramilitary offensives attempted to dislodge the FARC guerrillas from this strategic stronghold.

The now extinct Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC), United Self-Defense Groups of Colombia, paramilitaries committed the 1996 and 1997 massacres of El Aro and La Granja, which the Inter-American Human Rights Commission declared crimes against humanity. Paramilitaries also burned down El Cedral and Santa Lucia and displaced residents en masse in October 2000.

By 2006, the guerrillas had decisively defeated the AUC offensives but at a heavy human cost. Testimonies describe dump trucks filled with dead and rural roads lined with beheaded paramilitaries. The FARC kept control of the region until their demobilization in 2017.

“The paramilitaries always remembered what happened to them in Ituango. They see everyone here as guerrillas,” said Wilmer.

Armed group patrolling Nudo del Paramillo (Nicolas Bedoya/ VELA Collective).

Violence returns

After the FARC guerrillas withdrew from their territories and disarmed in 2017, many of Colombia’s rural regions were left with no authority. Ituango only had eight months of peace after the 2016 peace agreement before the killings started up again. The strategic region of Ituango is once again being contested in a bloody war between paramilitaries, security forces, and FARC dissidents.

According to the SAT report, the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC), or Gaitan Colombian Self-Defense Group, paramilitary emerged from the failed AUC demobilization in 2006. They have been slowly consolidating a path that cuts through the Nudo del Paramillo with the goal of linking up their territories in Bajo Cauca to the west and Peque to the south. After 30 years, the paramilitaries have finally been able to gain a foothold in their former enemy’s territory.

Many leaders believe the blood spilling is only going to get worse. Guerrillas disillusioned with the faltering peace process formed the “New FARC 18th Front Cacique Coyara” at the end of 2017. Several experienced former guerrillas and have quickly grown the group’s ranks by recruiting youth in their total war against the AGC.

Communiques from the dissidents have stated their intention of a “paramilitary cleansing.”

“There is a lot of fear and no security. There are no guarantees for civilians and much less for us ex-combatants,” said Wilmer. “If anything, the army sends troops to our canyon and they stay twenty days, a month at most. After that, armed groups can do what they want with the communities.”

So far, the army and police have been unable to effectively combat these groups and outpace their ability to recruit. Security forces themselves have been accused of serious human rights abuses and extrajudicial killings known as “false positives.”

This is the practice of the army killing civilians and presenting them as guerrillas killed in combat. The peak of the practice took place during the administration of former President Alvaro Uribe Velez in the mid-2000s but continues today.

Dissidents train new recruits in live fire. (Nicolas Bedoya/ VELA Collective)

Local conflicts persist

Ituango’s mayor, Mauricio Mira, embodies the open wounds left by Colombia’s civil war. Mira was blocked from running for mayor in 2015 by the FARC guerrillas.

“The guerrillas kidnapped me for three days, I’ve received several death threats, and was then displaced in 2015,” Mira told LAND.

But he has also disparaged communities like El Cedral. As a candidate in October 2019, Mauricio Mira said in an interview with LAND that the people in El Cedral are “lazy” and that, “Every time there is a displacement, they are the first to be ready to go to see what they can get.”

He won the 2019 mayoral election by just 100 votes.

Displaced prepare to return to their communities after four days (Pablo Cuellar/ VELA Collective)

Mira’s first major emergency as mayor would be the mass displacement of the community he stigmatized. The government and mayor’s office provided food and hygiene kits and supported the voluntary return of the communities.

“In Ituango, the army should have occupied the land that was left by the FARC after the peace process,” said Mira. “While the territory has coca crops for cocaine production, we will never get rid of the armed groups.”

The inhabitants of El Cedral, who themselves don’t grow coca but live in the strategic canyon between coca fields and the rest of the country, expect to be displaced again in a few months as the violence picks up.

The murder of an boy on March 22 and a dissident commander five days later in one of the displaced communities is a reminder that the conflict won’t stop, even with the onset of coronavirus.

At least Ituango has a head start mitigating the spread of the new virus. Since last year, armed groups have enforced a 6pm curfew.

While the people of El Cedral returned home, the risk of violence in Ituango remains.

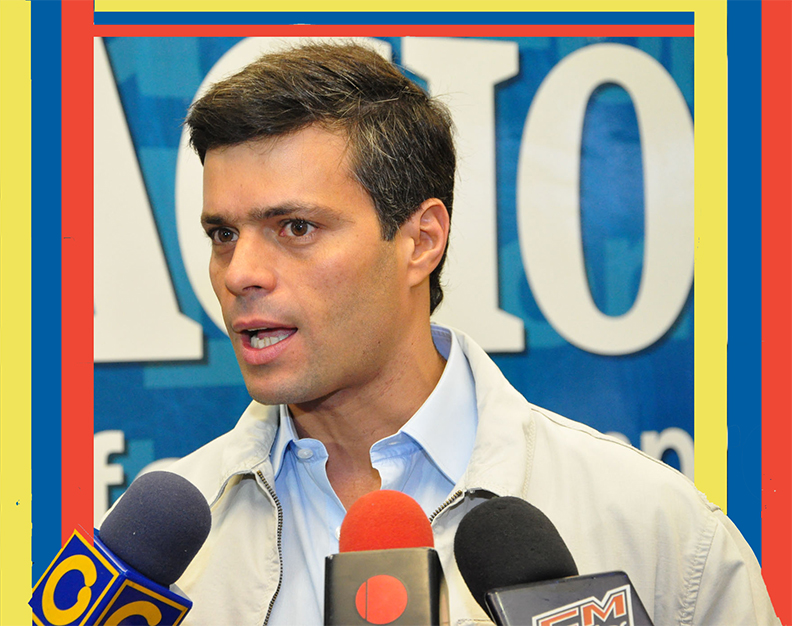

Mayor of Ituango (far left with glasses) listens to Augustin, the former FARC 18th front commander, speak. (Nicolas Bedoya/ VELA Collective)