Argentina, Dispatches, Features, Photo Essays, Southern Cone

The Long Shadow of Argentina’s Shale Boom

April 20, 2020 By Ignacio Conese

NEUQUÉN, Argentina— The Vaca Muerta region of Argentina is the promised land of unconventional oil and gas production. But as the shale industry struggles amidst the market crash, the social and environmental toll of Argentina’s fracking industry becomes increasingly clear.

The basin of Vaca Muerta is one of the largest non-conventional oil and gas developments in the world outside of the United States and Canada. The United States Department of Energy ranks it the world’s second-largest shale gas and fourth-largest oil reserve. Located in northern Patagonia, Vaca Muerta spans Neuquén province and parts of Mendoza, Rio Negro and La Pampa provinces.

The government of Cristina Fernández kickstarted the industry in 2013, with a series of gas production subsidies. These incentives continued and increased in the first two years of the Mauricio Macri presidency. Companies were guaranteed a baseline price that more than doubled the international market price. The difference would be covered first by the state, and then the local market.

Fracking site next to farm in Tratayen, Neuquén province. Photo: Ignacio Conese.

From 2016 to 2017, these incentives were so significant that in cases like Wintershall and BP, represented by its subsidiary Pan American Energy, government subsidies to these companies were larger than their total investments in the basin. Tecpetrol has taken the Argentinian state to court over to claim subsidies that almost equal the total of investments the company made in the basin.

Foreign investment in Vaca Muerta has not materialized as planned. According to the government, since 2013, foreign investments only makes up 35 percent of total investments. Most of this investment was in the early years. Currently no major foreign companies having large scale plans for the area. The only large player at this point in Vaca Muerta is the partially state-owned YPF company, which is Argentina’s main oil and gas player.

One of the International Monetary Fund conditions to bail out Argentina was reducing public subsidies, which the government did in 2019. The industries have responded to the reductions by decreasing drillings and fracking, delaying investments and laying off some 1,900 employees from drilling, pressure pumpers and service companies like Weatherford and Schlumberger.

Five wells in the same location of tight gas extraction in what used to be until recent years century old fruit plantations in Allen, Rio Negro province. Photo: Ignacio Conese.

Vaca Muerta is only an attractive investment if the government keeps funding the industry. With government budgets drying up, and the Argentinian economy on an IMF-respirator since 2018, unconventional energy resources in Vaca Muerta are a risky investment. The coronavirus-related economic downturn and the Arab-Russian Oil price war are beginning to hit Argentina and will further discourage investment.

In Neuquen province, the oil and gas industry are connected to every structure of governance and social networks. The provincial government’s budget depends on royalties to pay teachers, doctors, policemen, ministers and clerks. Everyone has a relative or close friend working in oil or gas or a business providing services to the industry. This economic and social landscape means operators working in the basin hold significant sway. Environmental policing is often ineffective because inspectors in the province do not have the capacity to prevent violations, and instead are always reacting to accidents, spills or leaks. Financial penalties are infrequent and low.

A source in one of the two major American pressure pumpers told LAND that it is cheaper for the company to be environmentally reckless and pay the penalties, when they are enforced, than to comply with the relatively lax environmental regulations in place. Another source in the powerful Oil and Gas Workers Union expressed a similar sentiment.

The source, who asked to remain anonymous, said, “Companies do whatever they want, and what they always want is to cut cost. Nobody can expect that workers will be the ones denouncing this, it’s not our job, nor our responsibility. It’s the province’s responsibility, the government has to enforce environmental regulations on the companies.”

Gathering in the Mapuche Community of Campo Maripe, near Añelo, Neuquén province. The basin started development seven years ago when YPF, on a joint venture with Chevron, started drilling and fracking in the Loma Campana concession, in territories claimed by the local Mapuche Community of Campo Maripe. The community faced an invasion and complete modification of their land. Photo: Ignacio Conese.

Nine of the ten concessions currently in post pilot stage or development in the basin are next to the Neuquen and Negro Rivers, or the Los Barreales and Mari Menuco Lakes, which are the only sources of freshwater for the most populated cities in the area. These bodies of water provide billions of liters that the petrochemical industry combines with sand and hundreds of chemicals to inject into the shale formations for hydrofracturing.

The small town of Sauzal Bonito has shaken more than 150 times since fracking activities began nearby in the year 2015. Previously, the town had never experienced earthquakes.

More than 90 percent of the 120 houses in the town now have structural damage. The authorities have replaced three houses and brought geologists to talk to the population. In the words of Adrian Sandoval, who lives in Sauzal Bonito, “They think that because we are from the countryside that we’re fools.”

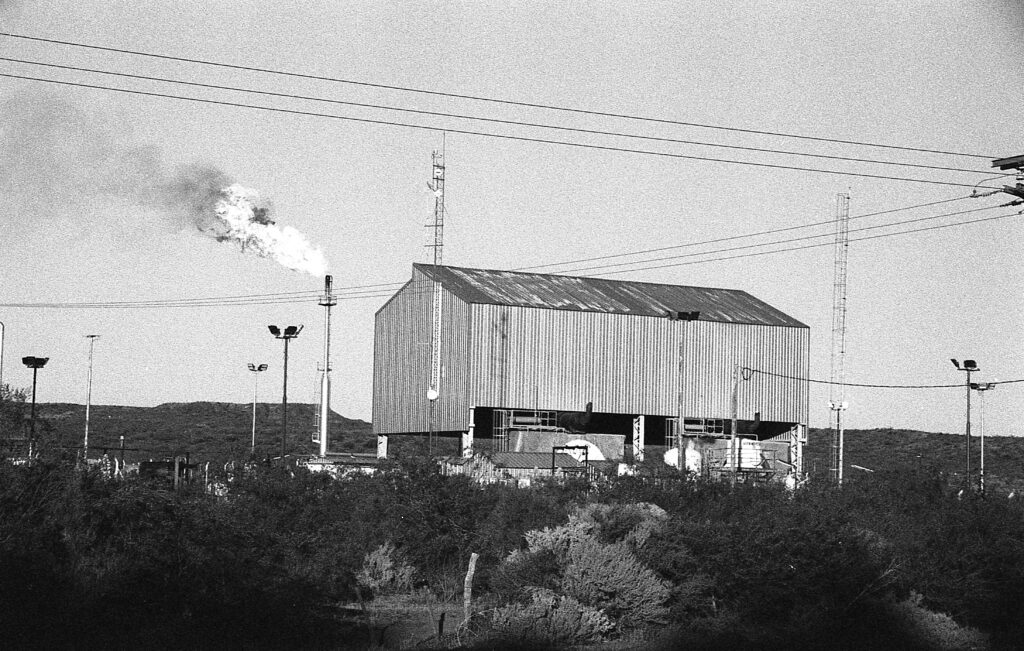

Companies like Shell have admitted that they flare 30 percent above what their supposed to, due to seasonal demand and lack of infrastructure in pipelines and LNG plants. The gases in flaring contribute to climate change. Photo: Ignacio Conese.

Añelo is considered the heart of Vaca Muerta. Since fracking activities began in the Loma Campana field in 2013, the town went from a population of 3,000 to nearly 9,000 The field is a joint venture between Chevron and YPF. In an area that used to be inhabited by poor ranchers and Mapuche Indigenous people, there are now man-camps, entire neighborhoods without services, hundreds of newly built dirt and gravel roads, and thousands of trucks and pickups in never-ending motion.

“Living the consequences of the oil business is nothing new for us,” says Jorge Nawel, of the Neuquen Mapuche Confederation. “It’s been a struggle over the past century for us Mapuche. It has also become part of many of our peoples’ lives, and it’s something that we’re not inherently against. But fracking is different. We see it in our territories and it’s present in our blood, polluted with all sorts of chemicals because it’s in the water that we drink, in the water that our animals drink, it’s in the summer air with the open flares, it’s in the soil that drillers leave behind.”

Almost 18 percent of YPF total oil production comes from the Loma Campana oil field, a land partially claimed or disputed by the Mapuche. But the local Indigenous Community of Campo Maripe hasn’t seen any returns from fracking, or any improvement in their quality of life. People have constantly harassed the community and specifically their leaders. The communities are forced to make do with what little territory they manage to maintain safe from the oil sites.

The town of Añelo is seen as the virtual capital of Vaca Muerta, filled with new constructions like hotels for senior employees. Photo: Ignacio Conese.

South of Neuquén, in the province of Rio Negro, also in the Vaca Muerta basin, non-conventional drilling and pumping developments have forced century-old pear and apple growers to go out of business. More than 10 percent of their lands have been turned into well sites, distribution pipelines, batteries, and gas related installations, in extraction sites developed by YPF. Most of these operations are concentrated in the city of Allen, which banned fracking in 2013, a decision overturned by the provincial government and later confirmed by the provincial Supreme Justice, favoring YPF and the Governor’s office.

Social organizations like the Allen Assembly for the Water have denounced an increase in cases of leukemia, skin and respiratory illnesses since fracking activities began. Non-profits including the Petroleum Observatory of the South (Observatorio Petrolero del Sur) and Greenpeace have spent years corroborating cases, while authorities and oil companies, deny, buyout and battle any voice of dissent.

Amado says that he used to live in Añelo but had to move out because of the high cost of living. Currently he tries to go every chance he has to take his grandson outside to explore fish and hunt. Near the Neuquén river in Añelo, Neuquén province. Photo: Ignacio Conese.

Exploiting Argentina’s shale gas reserves to their maximum potential would consume up to 15 percent of the entire global carbon budget for achieving the 1.5-degree Celsius Paris Agreement target. Argentina, a member of the Paris Agreement, has failed to implement real changes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The current economic tailspin may slow investment in Vaca Muerta. But as long as officials ignore the mounting social and environmental costs of unconventional gas and oil, political will remains to exploit Argentina’s shale resources.

Industrial park, Añelo, Neuquén province. Photo: Ignacio Conese.

Añelo is a town that has been completely occupied by the shale industry.

A casino next to the town’s centennial commemoration site. Añelo, Neuquén province.