Dispatches, Features, Mexico, North America

Amid Multiple Crises, a Remote Mexican Town Faces Threats of Illegal Mining Concessions

October 25, 2020 By Jacob Alabab-Moser

Los Chimalapas rainforest, located in the center of the Istmo of Tehuantepec in Oaxaca, Mexico, is host to some of the greatest biodiversity in Mexico and the world, and its nature has largely been preserved. Around 1.5 times the size of Rhode Island, its forests switch from high evergreen to low deciduous, strung together by mountain ranges and rivers that connect it with the rest of the Istmo. It now might face an existential crisis.

The Zoque people of the Los Chimalapas currently face the threat of four requests for mining concessions within their territory being approved by the Mexican federal government—a move that would exacerbate the devastating effects of both existing mining operations and several other social and political catastrophes in the region.

If the Ministry of Economy approves the concessions, “We would lose our autonomy,” said Gilberto Pacheco Sánchez, Zoque author and San Miguel Chimalapa resident. “How is it possible for someone to enter your house without permission?”

Yet, over the phone, he was optimistic. “Knowing the government of the Chimalapas, of the Zoques, of the fight of the pueblos, you don’t have to think twice. We’re not going to allow the mines to be installed,” he said. “We’re going to defend with our lives.”

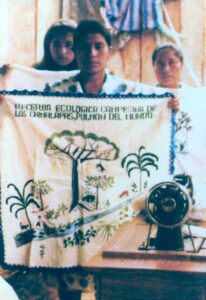

A member of The Istmo is Ours movement to preserve Los Chimalapas holds a banner reading “Peasant Ecological Reserve of Los Chimalapas, lung of the world.” (Photo courtesy of the Archivo de Maderas del Pueblo del Sureste, AC)

The two principal Zoque municipalities in Los Chimalapas, San Miguel Chimalapa and Santa María Chimalapa, together have held title to over approximately 594,000 hectares of communal lands since 1967. If the Ministry of Economy approves the four pending requests for concessions, mining companies would occupy 107,383.68 hectares with free reign to extract gold, silver, copper and lead. These would add to the 6,410 hectares that are already concessioned to the “Santa Martha” project by Canadian company Minaurum Gold SA de CV, located between the territories of Los Chimalapas and neighboring Zanatepec. Although the Zoque municipalities and assemblies own the rights to surface land, Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution states that the federal government owns all mineral deposits in national territory and, per the Mining Law, the General Directorate of Mines, which is housed within the Ministry of Economy, has the right to grant concessions for corporations to explore and exploit them.

Francisco López Bárcenas, Mixteco mining expert and professor and researcher at El Colegio de San Luis, said that the provisions in the 1992 Mining Law emerged from twenty years of reform catering to Mexican and foreign business interests alike. All concessions provide rights to the minerals, as well as the necessary soil and water, last fifty years with easy renewals, allow for the extraction of any type of mineral, and apply to the territory, not just the minerals to be extracted, he said.

Three of the possible legal protections that the federal government could provide for the situation in Los Chimalapas have proved hollow for the Zoque struggle against mining. Mexico ratified the 1989 Indigenous and Tribal Populations Convention of the International Labor Organization, better known as C169, which obliges governments to consult indigenous people regarding legislative and administrative measures that will affect them directly. In Los Chimalapas, “they have not been consulted,” or even warned by the government, said López Bárcenas.

In the past, the federal government aggressively pushed to designate Los Chimalapas as a federal biosphere reserve under its protection, like the Lacandón rainforest in neighboring Chiapas has been since 1978 as the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve. While this model could include the consultation of Zoque communities, “the management plan for a reserve stays in the hands of the Environmental and Natural Resources Ministry (SEMARNAT, in Spanish). The communities don’t participate” in the decision-making process, said Miguel Ángel García Aguirre, founder of NGOs Maderas del Pueblo del Sureste, A.C, and Comité Nacional para la Defensa y Conservación de Los Chimalapas. “It’s about autonomy, the right to self-determination.” He pointed out that even in the existing biosphere reserves, the government has permitted projects like mining concessions and highway constructions.

The Zoque have also tried demanding SEMARNAT to reject mining corporations’ Environmental Impact Statements (MIA, in Spanish), which the law requires for the granting of concessions. Yet, even if the Ministry were to side with them, it is uncertain that anything would change on the ground. According to its website, the “Santa Marta” project by Minaurum Gold already began operations including reconnaissance—a type of early mineral exploration—before the submission of its MIA to SEMARNAT on July 23, describing a “direct mining exploration with a drilling scope of 20 Drilling Units.”

A national forum for ‘The Istmo is Ours’ movement held in 1997. (Photo courtesy of the Archivo de Maderas del Pueblo del Sureste, AC)

On August 20, the municipality of San Miguel Chimalapa proclaimed that exploration permits for “Santa Martha” had been granted “without the Zoque communities’ consent, attacking our rights as indigenous people and ancestral owners of the territory.” SEMARNAT’s approval of Minaurum’s MIA overlooks “irreversible damages” to the environment, municipal leaders added.

Say one were to consider water alone and put aside diverse microclimates and endemic flora and fauna endemic of Los Chimalapas. If the requests for concessions are approved, their polygonal plots would cut through the Ostuta and Espíritu Santo Rivers, bringing contamination to the region’s aquifers. Moreover, the concessions would also affect the rivers that begin in Los Chimalapas and flow into the Upper and Lower Lagoons of the Gulf of Tehuantepec, where other pueblos originarios, the Ikoot and Zapotec, fish as a means of sustaining their families and culture.

The requests are for open-pit mines, several of which already exist in the Istmo de Tehuantepec. “They require lots of water to wash the land that is ground in order to obtain the metals,” says Bettina Cruz Velázquez, Zapotec human rights defender and spokesperson for the indigenous assembly Asamblea de Pueblos Indígenas en Defensa de la Tierra y el Territorio. “Effectively in the Istmo zone, for the presence of the Los Chimalapas rainforest, this water exists. It will be hoarded and occupied by the mines as well.”

“It seems to me that we need to rethink, then, what is wealth? Because I would say wealth is water,” said Josefa Sánchez Contreras, Zoque community defender from San Miguel Chimalapa and researcher at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, in an interview with TV UNAM. Mining, she said, only brings “monetary“ wealth and even then, it often doesn’t stay in Mexico.

Los Chimalapas amid the “megaprojects of death” and the agrarian conflicts

As the bearer of Mexico’s “Fourth Transformation,” President Andrés Manuel López Obrador projects himself to be the leftist champion of Mexico’s Indigenous and poor communities against mining threats. “We have not delivered a new mining concession since we arrived because it got out of hand” under “the neoliberal governments,” he said at a press conference last month. “You have to talk to the Zoque comrades and tell them not to worry that there is no concession there,” said Eduardo Enrique Flores Magón y López, General Director of Mines, at another press conference in September. “None of the companies has any right to extract, explore or anything that has to do with mining in those communities.”

Yet, even if his administration has not yet given any concessions, López Obrador has proved himself to be on the side of mining corporations by neglecting to derail concession requests. When he shut down several sectors in the Istmo de Tehuantepec during the current pandemic, he designated mining an “essential activity.” Moreover, the government has withheld transparency about the relevant processes from affected indigenous communities like the Zoque. There is not even a public portal with the complete list of all requested and granted mining concessions in Mexico. The scarcity of official communication pushed a group of Zoque youth in San Miguel Chimalapa in 2014 to form Colectivo Matza to fill this void. “Some friends received information and through an assembly, we communicated to the community that part of the Chimalapas had been concessioned,” said Colectivo member Abigail Garcia. Earlier this month, the collective held educational workshops in different neighborhoods about the new developments.

The government’s acceleration of mining operations makes sense, given their important role in plans over the past decade to develop the Istmo into the Interoceanic Corridor: a network of industrial parks, railway tracks, a superhighway, a refinery, wind farms and hydroelectric plants linking the Atlantic port of Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz with the Pacific one of Salina Cruz, Oaxaca. Construction of these “megaprojects of death”—as Indigenous groups in Oaxaca call them—drive demand for minerals, while mining companies would use the new Trans-Isthmian Train to transport goods from mines to the ports. “It is a kind of Panama Canal, but with a railroad,” the president said.

With the sudden influx of this economic development, the presence of organized crime and land privatization in the Istmo has surged, furthering the damage to indigenous pueblos and their communal lands. “The social fabric has been violated,” said Zapotec human rights defender Cruz Velázquez. The entry of transnational corporations into the region has severed its threads by offering jobs and little public works “that mean nothing to them but mean a lot to people here who have been abandoned by the government.”

Tensions over the megaprojects have exacerbated the complex webs of political and agrarian conflicts that have already afflicted Istmo communities for decades. For example, Indigenous resistance to the installation of wind farms by a French company played a part in the massacre at the Ikoot fishing community of San Mateo del Mar in June. Disagreements and a lack of communication about the project over the course of years contributed to a rift between the village’s traditional authority—the Council of Elders—and its elected Municipal Council, although the contention ultimately leading to a criminal group’s murder of 17 residents involved the election of the Municipal President, which some residents argued to be fradulent. “The massacre is part of the offensive of the regional powers that be, functional to the wind industry, to dismantle or weaken the organized nuclei that oppose the megaprojects and articulate the defense of their territory, their natural resources and their worldview,” wrote Luis Hernández Navarro in a La Jornada op-ed.

Likewise, the Zoque struggle against mining concessions served as the backdrop for a three-week-long blockade of San Miguel Chimalapas last month. Residents of municipal agencies surrounding the municipal capital blocked access on August 28 to the town’s sole highway and the entrance of food, medicine, and other essential supplies into the town. The blockaders demanded for Municipal President Francisco Sánchez Gutiérrez to distribute federal government funds. Yet days before, on August 20—as García Aguirre, Maderas del Pueblo founder, notes—the municipal council had denounced the mining concession requests and government inaction. Citizens backing the mayor “were on the brink of violently breaking the blockade,” added García Aguirre. Though feuding parties peacefully reached an agreement, “this could have provoked a bloody standoff like San Mateo del Mar.”

The San Miguel Chimalapa Municipal Council and Colectivo Matza request international support for its fight against mining concessions. All interested should fill out this form.

Jacob Alabab-Moser is a Mexico City-based freelance journalist.