Brazil, Dispatches, Features, Regions, Southern Cone

Pandemic Intensifies Hardships for Brazilian Indigenous Communities

July 23, 2020 By camillegarcia

The coronavirus has affected Indigenous communities in every part of Brazil, according to a recent report by the Indigenous advocacy group Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB). As of July 17, APIB reported that 16,057 Indigenous people across the country have been infected with the virus and 529 have died from it.

The state of Amazonas, home to the country’s largest Indigenous population, has recorded 179 Indigenous deaths, the highest death toll of Indigenous people in Brazil. APIB researchers have deemed the situation a genocide of Indigenous people by the federal government. In addition to rising infections, these communities also have experienced a breakdown of their health system, loggers and miners invading their lands, and a lack of government-provided medical resources and professionals.

“The failures of the [Jair] Bolsonaro government and its violations of human rights hark back to the necro-policy of the military dictatorship which used the dismantling of the Indigenous healthcare system, deliberate contamination with infectious and contagious diseases, forced removals and torture as the basis for Indigenous genocide,” the APIB report says.

For many Indigenous groups, the coronavirus is an unwelcome addition to a myriad of issues they have already been facing for years. One such group is the Hupda, an Indigenous community deep in Brazil’s Northwest Amazonian region bordering Colombia. They are among the country’s most vulnerable groups. Researchers have confirmed that there are some cases of the virus among the Hupda, but the exact number is still being determined.

Still, long before the coronavirus was brought to their region, the community of about 2,000 people was already dealing with discrimination and widespread malnutrition while trying to preserve their language, traditions, and land. One of the most troubling issues currently facing the community is an unprecedented suicide rate. This complex occurrence affects some Hupda as young as 14.

These are only a few examples of the systemic marginalization and oppression the Hupda and other Indigenous groups in Brazil have faced for decades, says Danilo Paiva Ramos, an anthropology professor at the Federal University of Bahia who works closely with the Hupda.

Joint efforts by Hupda leaders and anthropologists to address these problems come to a halt as they have been forced to shift their focus to preventing the spread of the coronavirus and to getting the Hupda the necessary resources to treat it.

Américo Socot, a Hupda leader, has been a vocal and integral figure advocating for his community. He said he is frustrated that the coronavirus has added yet another hurdle to the Hupda’s battle to improve health care and education, and that the community is not getting the support it needs.

The coronavirus pandemic in Brazil, like the United States, has shone a light on the cracks within the Brazilian healthcare and governing system, felt especially by marginalized groups such as Indigenous people, Ramos said. For many, access to resources such as healthcare and government welfare is limited. About 110 Indigenous territories in the state of Amazonas are in danger due to the coronavirus, according to the APIB report, and are still awaiting funds, medical supplies, and staff for emergency care amid the pandemic.

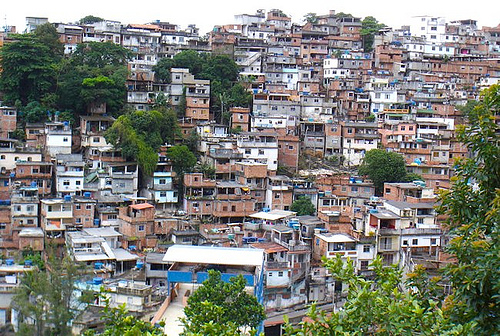

The Hupda, who live deep in the Amazon forest along the Upper Rio Negro, have to make a long and at times dangerous boat journey to the nearest town, São Gabriel da Cachoeira, to go to a hospital, stock up on supplies, or to collect their welfare money through the federal Bolsa Familia program.

Other dangers await them once they arrive in São Gabriel. There, Ramos said, the Hupda experience discrimination and extreme difficulty collecting their funds while navigating the bureaucratic system in Portuguese, not their native tongue Hup.

Sometimes the welfare money is not enough to get the Hupda back home, and many have fallen into debt to buy supplies in hopes of returning to their villages. And, along other complex factors, researchers such as Ramos also believe that the racist and anti-Indigenous discrimination the Hupda face in urban areas has likely contributed to the high rates of suicide in the community.

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, traveling and shipping supplies along the Rio Negro has become a method for transporting the virus from larger cities such as Manaus—550 miles from São Gabriel—to more remote areas, such as the Hupda’s forest reserve. Manaus’s healthcare system and residents were hit hard by the virus in the early days of the pandemic. As of July 19, the city recorded 1,963 deaths, according to the Brazilian Health Ministry. Passenger boats from the city were banned from docking in São Gabriel, but private boats have continued to arrive. The APIB report states that many infections in Indigenous territories are due to people contracting the virus in more urban areas and bringing it back to their homes.

“We are very worried about this [situation],” Ramos says. “Recently-contacted Indigenous groups like the Hupda and others are specifically sensitive to this kind of contagious virus epidemic.”

Policies under President Jair Bolsonaro compound these issues, Ramos says. Bolsonaro, who has been downplaying the severity of the coronavirus pandemic from the start, has been dismantling Indigenous rights, opening Indigenous lands for commercial development, and has ridiculed Brazil’s Indigenous communities. Mining and deforestation in the Amazon, allowed and encouraged by Bolsonaro, has already led to the invasion of Yanomami lands by about 20,000 land prospectors who are likely to also be spreading the virus in the area, the APIB report states.

Bolsonaro’s disregard for Brazil’s Indigenous populations and their land, and his government’s lack of medical and financial support for these communities have raised concerns among Indigenous people and advocates for the health and longevity of these communities.

The Hupda and their ways of life have changed considerably over the years. The sustained presence of Catholic and Evangelical missionaries in their communities has disrupted the Hupda’s traditional methods of living, educating their youth, and hunting and gathering. The prevalence of suicide, which started in the early 2000s, is complex; some Hupda and researchers attribute the phenomena to a mix of factors including racial discrimination, difficulties dealing with the Brazilian governing system not built for them, witch craft, and a lack of health resources.

Before the pandemic, Socot—the Hupda leader—his community, and researchers had crafted a “Plan de Vida,” a document to share with government officials, researchers, missionaries, and others that outlines the Hupda’s concerns and desires for the preservation and advancement of their population, their language, their land, and their traditions. The Hupda want to teach their youth to read and write in their native language and to write books containing their ancestral knowledge and traditions, Socot said. They want to map and protect their sacred land and be able to rely on a more effective and accessible health system, all while remaining and thriving in their forest villages.

Ramos said that between the pandemic and the current political situation it is unclear when the Hupda’s wishes will be able to be met.

“This coronavirus [pandemic],” he said, “is increasing all the problems that Indigenous and recently-contacted Indigenous populations are already facing.”