Brazil, Features, Southern Cone

Brazil’s Jan. 8 Shows the Influence of Anti-Communist Rhetoric

January 12, 2023 By Alfredo Eladio Moreno

It is clear Bolsonaro’s public crusade sowing doubt in the integrity of Brazil’s democracy and elections inspired protestors to attack the Brazilian capital on Jan. 8. But under this patina of deliberate disinformation lies something else: a general phobia of communism that conflates it to leftist leadership.

A powerful force mobilizing right-wing movements into action, the logic of communist phobia is simple: Because Lula is a leftist, he will turn Brazil into a communist country.

When Jack Nicas, Brazil Bureau Chief for the New York Times, asked a protester what his purpose was for protesting a day before Lula’s inauguration he said, “What we want is for our country not to be host to a communist government.”

His name is Magno Rodrigues, and he caught Nicas’ attention after he had spoken over microphone to a crowd of protestors who were encamping outside army headquarters in Brasília. Nicas asked Rodrigues how long he was willing to continue his cause. “As long as it takes to free my country,” Rodrigues said.

One week later on Jan. 8, protestors like Rodrigues descended on the Three Powers Plaza, where the Brazilian government’s executive, legislative and judicial powers sit.

Videos of the attack show how riotous and awkward it was. One person thrashed at the windows of the supreme court with a metallic object, and another meandered about looking around at the mayhem, while his compatriot belted out a call to action.

In a video posted to Contragolpe Brasil — an Instagram account with one million followers that identifies the people who attacked the capitol — Caio Enrico Lima from Hortolândia is recording himself descending on the esplanade of the Three Powers Plaza. “Communism here? No! Dictatorship here? No!” he yells.

Since the attack happened, it has been impossible to deny the similarities between the events in Brazil on Jan. 8 and the insurrection at the United States Capitol on January 6, 2021.

Like its U.S. counterpart, Brazil’s Jan. 8 has been characterized symbolically as an “assault on the heart of Brazil’s democracy.” Similarly, former military officers and armed forces analysts celebrate the military’s obedience to Lula’s orders to restore order as a “victorious moment” for democracy.

What happened on Jan. 8 does not merely stem from a skepticism of democracy. It is right-wing Brazilians’ response to a supposedly dysfunctional system of governance under threat by a supposed communist.

In ironic fashion, right-wing movements like the one seen in Brazil employ anti-democratic techniques and support authoritarian rulers who claim to safeguard the country from the threat of communism coming from the other side.

The threat of communism has become a fundamental fear among right-wing movements, impelling them to action against leftist leadership.

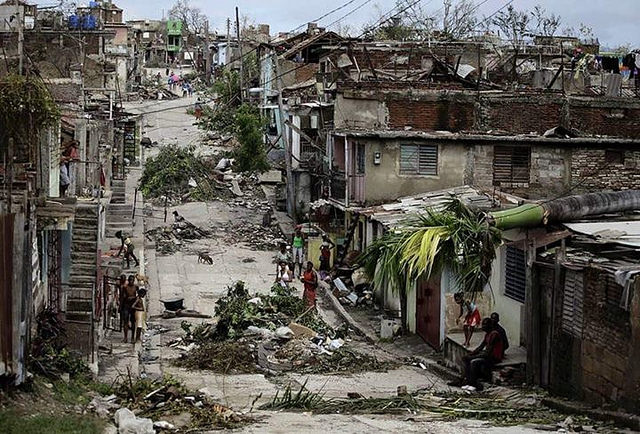

But for all the term is worth, it is nebulous at best. “Communism” does not actually have to refer to a specific set of policies to inspire fear among its dissidents. Rather, when employed by right-wing movements, the term swiftly and conveniently recalls the weight of Latin America’s experience with leftist leaders in the past — only some of whom instituted hardline socialist and communist policies. None weigh heavier on recent memory in the region and the world than Hugo Chavez of Venezuela.

The argument usually unfolds as follows: Chavez was the leader of Venezuela’s socialist party, Chavez expropriated international oil and Chavez came before the economic downturn in Venezuela, ergo Chávez and socialism (and therefore communism) are bad.

The logic is grossly reductionist, but it works. Today, all the term has to do to politically motivate people is recall a generalized fear of leftist leadership, which according to right-wing logic, would devolve the country into communist mayhem.

The fear of communism has long haunted Brazil. Between 1935 and 1937 two major conspiracy theories arose that claimed communist plots to overthrow the government were brewing in the country. Both were false, the first forged by a right-wing newspaper and the second by the fascist General Olímpio Mourão Filho. The conspiracies legitimized Getúlio Vargas’ moves to establish a dictatorship in the country.

“The red menace is the most powerful threat used to scare Brazilians—both in the past and today,” historian Rodrigo Patto Sá Motta told Vincent Bevins. Two years ago, Bevins reported on the atmosphere of anti-communist conspiracy that, like it did for Brazil’s erstwhile heads of state, propelled Jair Bolsonaro to Brazil’s highest office.

While leftist leaders relished in the buoyancy of Latin America’s pink tide, “a constellation of conservative thinkers, influenced by American internet culture and driven by conspiracy theory, were slowly rising to power,” Bevins said.

During the 2018 election when Bolsonaro was first elected, anti-communist rhetoric benefited from the platform it found on Twitter. Users posted hundreds of tweets relating to anti-communism and election, essentially making the topic go viral.

A study that analyzed tweets mentioning communism by theme found that they were associated with “suspicion of electronic ballot boxes, distrust of public institutions, corruption, and perceived threats to religion and morality.” As a whole, the tweets showed that at the heart of anti-communist sentiment is disdain for the influence of leftist leadership on the political system.

Jan. 8 was a condemnation of communism — not in actuality, but in anticipation and not by ballot box, but by violent and anti-democratic action.

The politics of anti-communist are effective. It’s the reason why Republicans in the U.S. can count on a solid base of support in Florida. There, Republicans have courted Latin Americans — many of whom come from countries with a historically overt leftist presence like Cuba, Colombia and Nicaragua — by peddling assurances against communism.

If Florida has actually become a bastion of anti-communism, then it could be the reason why it became a refuge for Jair Bolsonaro, who has since been spotted at places like a Publix supermarket. Now, Bolsonaro lives in mundanity and in exile from the upper echelons of Brazilian politics.

Bolsonaro has trafficked in anti-communist rhetoric as a cornerstone of his and his closest allies’ politics. Even so, protesters like Rodrigues and Lima are aligned with Bolsonaro insofar as Bolsonaro is aligned with anti-communism.

What happened on Jan. 8 is simple to explain. It is the combined result of a president’s yearslong effort to delude his supporters into believing its elections and democracy are at risk, and a general phobia of communism among a conservative base willing to use any means necessary to prevent it from taking root.

Some 1,200 to 1,500 people have been detained for questioning in the aftermath of the riot. The leaders of each branch of government, including Lula, released a joint statement “in defense of democracy,” saying they “reject the terrorist acts, vandalism, criminals and coup plotters,” that took place on Jan. 8.

Moving forward, there is hard work to be done. The government will have to respond to the Jan. 8 attack by holding to account those who were responsible, and by disseminating truthful information about what happened. In some ways, it has already done this. The senate has called for an investigation into the attack, and the Brazilian authorities have now turned their attention to the politicians and business elites who had a part to play in the attack.

Even more important will be the way Brazilian society responds in combating disinformation stemming from anti-communist rhetoric.

About Alfredo Eladio Moreno

Fredo is a journalist and photographer from his native Houston, Texas. He has reported since 2020 on Mexican politics and immigration policy in the United States, and especially on Nicaragua and the Ortega-Murillo regime. He is a graduate student of Journalism and Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University, where he is Editor-in-Chief of the Latin America News Dispatch.