Features, Southern Cone, Uruguay

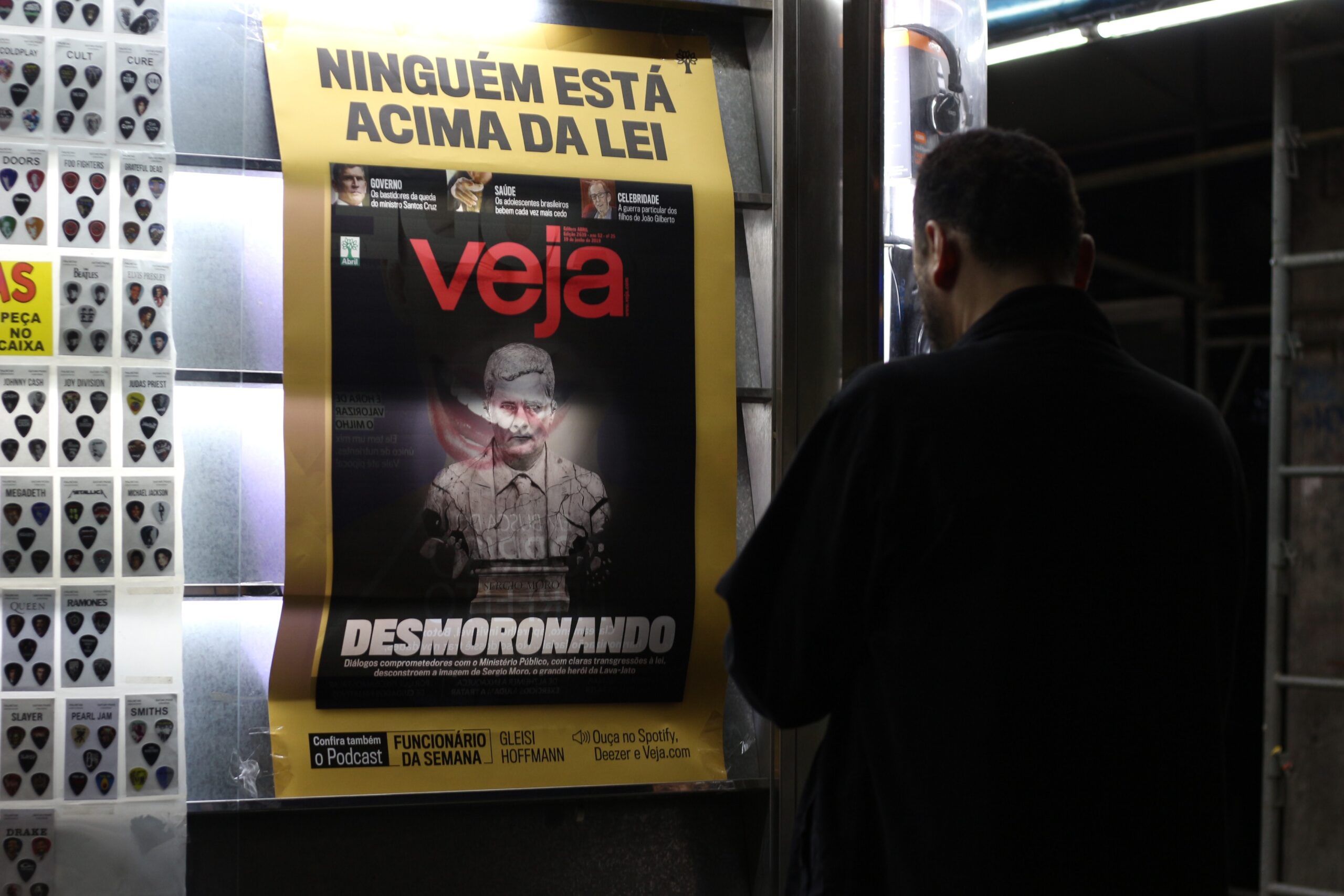

A Corruption Scandal Is Making Waves in ‘Squeaky-Clean’ Uruguay

January 30, 2023 By Laurence Blair

This article was republished with permission from World Politics Review. To view the original, click here.

The story was damaging enough to begin with. Last September, Alejandro Astesiano — chief bodyguard to Uruguay’s center-right president, Luis Lacalle Pou — was arrested in the presidential residence, soon after returning with his boss from a family holiday abroad.

According to prosecutors, Astesiano had used his privileged position to sell fake birth certificates to dozens, and perhaps even hundreds, of foreign citizens seeking to claim Uruguayan passports via ancestry — especially Russians seeking to escape their country in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine. While Astesiano seems to have inherited the racket, which reportedly goes as far back as 2013, the vast majority of fake documents have been issued while Lacalle Pou was president.

Lacalle Pou seemed shocked and blindsided. After all, he insisted, Astesiano — a close friend of two decades — had no previous criminal record. But media reports subsequently revealed that the 47-year-old former chauffeur and police officer has had more than 20 brushes with the law, including for alleged acts of fraud, theft and property damage.

Then in November, a local newspaper, La Diaria, reported that the forgery investigation had uncovered evidence on Astesiano’s phone and other devices that he had offered to use spyware owned by the Ministry of the Interior on behalf of multiple business figures in exchange for payments.

In particular, Astesiano reportedly intercepted calls between two opposition senators in order to secure personal information that could benefit Vertical Skies — a security consultancy made up of several former Uruguayan military officials — in connection with public contracts in the port of Montevideo. The newspaper also suggested that Vertical Skies asked Astesiano for insider help in selling patrol boats and planes to Uruguay’s armed forces.

As yet, prosecutors are reportedly not investigating the espionage allegations. Astesiano has denied any wrongdoing. Interior Minister Luis Alberto Heber has denied that any calls were intercepted. And it is not clear that Astesiano actually had access to the spyware. But after testifying in the forgery case in late November, the secretary of the presidency, Alvaro Delgado, conceded to the press that, if true, the claims are “very serious.” In late December, it further emerged that Astesiano had sought information from the security detail for Lacalle Pou’s ex-wife, as well as from police, about a trip she had taken two months after they separated.

With its mafia-esque overtones, the scandal is making waves in famously placid Uruguay. The country is known for boasting a squeaky-clean democracy that tops indices measuring quality of life and government transparency in South America. But the unfolding story has also severely damaged the administration of Lacalle Pou, who was interviewed by the prosecutor leading the case for four hours in private in late December.

In winning the presidency in November 2019, Lacalle Pou, a lawyer and former congressman with the Partido Nacional, or National Party, ended 15 years of rule by the leftist Frente Amplio, or Broad Front, coalition. Now 49, he is a relatively youthful face in a country whose political heavyweights tend to be octogenarians. But as the son of former President Luis Alberto Lacalle, who governed from 1990 to 1995, he is also a familiar one.

Until the recent scandal, Lacalle Pou had enjoyed solid approval ratings. He initially handled the COVID-19 pandemic adroitly — closing some borders and testing aggressively while eschewing obligatory lockdowns — even if the decision in mid-2021 to drop most measures and rely entirely on vaccinations caused deaths to spike.

In July 2020, he successfully passed a package of some 135 reforms known as the Law of Urgent Consideration, or LUC, which broadly sought to improve education, boost police powers to combat increasingly bold narcotrafficking gangs and add greater flexibility to the economy. The reform package narrowly survived an opposition-backed referendum seeking to overturn it in March 2022.

Lacalle Pou’s emphasis on improving education has struck home, given the poor quality of secondary schools in many parts of the country. His drive to expand Uruguay’s international imports and exports has resonated after years of anemic economic growth. These efforts include a potential free trade agreement with China and an application to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership, despite the fact that as a member of Mercosur — the stalling regional trade bloc that includes Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay — Uruguay technically can’t negotiate such deals unilaterally.

Even his planned reforms to make the social security system more fiscally sustainable, including by raising the retirement age from 60 to 65, has been met with grudging public acceptance. The reforms made it past the Senate in December in the teeth of stiff Frente Amplio opposition and now await approval in the lower house.

But this run of good fortune now seems to have ended. At the time of Astesiano’s arrest, Lacalle Pou’s approval rating stood at 49 percent, according to Equipos Consultores. Since then, it has dropped to 39 percent, the sharpest fall since his rating plunged from 60 to 47 percent between May and July 2021, at the height of the pandemic. As the scandal unfolds further, it is likely to slide even more.

Adding to the popular discontent with the government, the polling firm suggests, is the case of Sebastian Marset. Reportedly a regional criminal mastermind and the founder of the Primer Cartel Uruguayo, or First Uruguayan Cartel, Marset is wanted by Interpol for allegedly moving some 16 tons of cocaine from Paraguay to Europe via Uruguay, which along with other Southern Cone countries has become a new route for traffickers. Yet, it emerged last August, when Marset was detained in Dubai in late 2021 while traveling on a false Paraguayan passport, he was quickly issued a Uruguayan one, enabling him to escape. Deputy Foreign Minister Carolina Ache Batlle resigned in December over the scandal, amid an investigation into whether senior figures in Uruguay’s Foreign and Interior Ministries helped Marset get away.

Late January kicks off Carnival season in Uruguay, which includes packed concerts by the country’s murgas, or groups of satirical troubadours, broadcast live to the nation. Given that a third of the public thinks crime is the biggest issue facing the country, these groups are already preparing to taunt the government, making hay of Lacalle Pou’s emphasis on law and order, even as a criminal ring has been operating within the halls of power.

Declining public confidence may hamper Lacalle Pou’s reform agenda by causing fissures within his five-party coalition. It is also likely to make him politically toxic as early attention begins to turn to the next general election in October 2024. Sitting presidents are ineligible for immediate reelection in Uruguay, but Lacalle Pou has no obvious successor-in-waiting in his National Party, and he is now unlikely to play a meaningful role in selecting one.

In fact, according to a November poll by Usina de Percepcion Ciudadana, 28 percent of respondents think the next president will be Yamandu Orsi, a former high school history teacher and the Frente Amplio mayor of Canelones, Uruguay’s second-most populous district. Meanwhile, 15 percent support Carolina Cosse, the mayor of Montevideo and also a Frente Amplio stalwart. The best-performing government figure was Delgado, the presidency secretary, receiving 12 percent.

Still, elections are still nearly two years away. If closer trade ties with China — the destination of over a third of Uruguay’s exports by value — can be pulled off without provoking a rupture with Mercosur and the economy picks up speed, the government’s popularity may recover.

Nor should the recent dents to the credibility of Uruguay’s institutions be overstated. Compared to its peers — with annual inflation nearing 100 percent in Argentina; Bolsonaristas storming Congress in Brazil; and Paraguayan leaders being sanctioned by Washington for corruption and even terrorist links — Uruguay still looks like an oasis of stability and rule of law. It also boasts a rare degree of cross-party cohesion on matters of state, illustrated by Lacalle Pou attending the Jan. 1 inauguration of Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva accompanied by former Presidents Jose Mujica, of the Frente Amplio, and Julio Maria Sanguinetti, of the Colorado Party.

Yet the latest scandals suggest that Uruguay cannot afford to be complacent against the tentacles of corruption and organized crime. They also hint that, just as the country’s Carnival season is beginning, Lacalle Pou’s long political honeymoon has come to a close.

About Laurence Blair

Laurence Blair is a freelance journalist based between London and Latin America. He is currently writing a book on South American history for Bodley Head/Penguin Random House, to be published in 2020. Follow him on Twitter at @laurieablair.

< Previous Article

January 18, 2023 > Euan Marshall

Unifying Brazil will be Lula’s biggest challenge in office

Next Article >