Central America, El Salvador, Photo Essays

Community Roundtable in El Salvador Seeks to Mitigate Violence

September 29, 2014 By Danielle Mackey

ILOPANGO, El Salvador — In 2012, the two major Salvadoran gangs, MS-13 and the 18th Street Gang, brokered a truce supported by the government. The gang leaders agreed to stop violence and recruitment, to turn in weapons and to begin regular negotiations between incarcerated gang bosses. The homicide rate immediately dropped by half and foot soldiers of both gangs received orders to join local pacification efforts.

An unknown number of these efforts cropped up in communities across the country. Some were sponsored by money from foreign governments, but others, like this roundtable in Ilopango, El Salvador, were initiatives by neighbors tired of violence. The roundtable meets once monthly and brings together people who might otherwise never speak: community leaders, gang members and school officials.

In 2012, Ilopango’s homicide rate fell so drastically that it was the first to be declared a post-truce “violence-free municipality” by the government. However in late 2013, the truce slowly fell apart—commitments weren’t fully kept by either the gangs or the authorities, many say—and the murder rate has risen back to its pre-truce level, making El Salvador once again one of the world’s most violent countries.

There is a long history of favoring repression over dialogue when it comes to solutions to violence in El Salvador. As a result, the social stigma for participating in initiatives like the Ilopango round table can be high. Furthermore, recent actions by the Salvadoran attorney general signal a criminalization of dialogue.

Nevertheless, the Ilopango roundtable forges ahead—evidence that, although the truce may have collapsed on an official level, the breathing room it offered gave rise to a decentralized, grassroots peace process that continues.

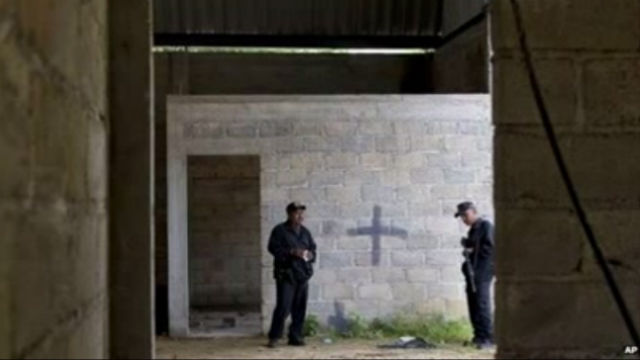

The entrance to the La Selva neighborhood, located in Ilopango, El Salvador. The graffiti on the right marks the community as territory of the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) gang. La Selva is one of 29 communities in the municipality that, one year ago, initiated an experimental dialogue roundtable of gang members, community leaders and school officials who come together once a month. The roundtable receives legal and psychological support from a Salvadoran human rights organization, the Foundation for the Study of the Application of the Law (FESPAD).

On Aug. 17, roundtable members gathered in the community center of Amatitan, a neighborhood near La Selva. They talked about relationship-building and brainstormed ways to intervene in a conflict in one of the 29 communities over the administration of its water system. They also celebrated the progress they had made on rolling back abuse by the police and army against the youth in their communities.

Eighteen-year-old Ceferino Lemus is a member of the MS-13 gang. “I’m here because I believe in dialogue,” he said. “Here (on the roundtable) we have good communication: people told us what we needed to change, and now we work together on problems like the lack of jobs, and poor education and nutrition. This space brings out the smiles we can’t share on the street,” he said. Not long ago, soldiers handcuffed Lemus, took him to the nearby lake and held him under water until he nearly drowned. His participation in the roundtable has helped him learn to work together with his neighborhood and to use dialogue to confront abuse.

Rosa America is a 55-year-old great-grandmother from the area. “Youth in this country are punished for the sin of being young,” she said. “I used to be terrified of them. But now I look around and I see kids who can still be saved,” America said. “I think dialogue is important, but I’m a woman who needs to see actions to believe. This was hard at first but we’ve seen important changes,” she said. She estimates that murders in her area went down 70% since 2012.

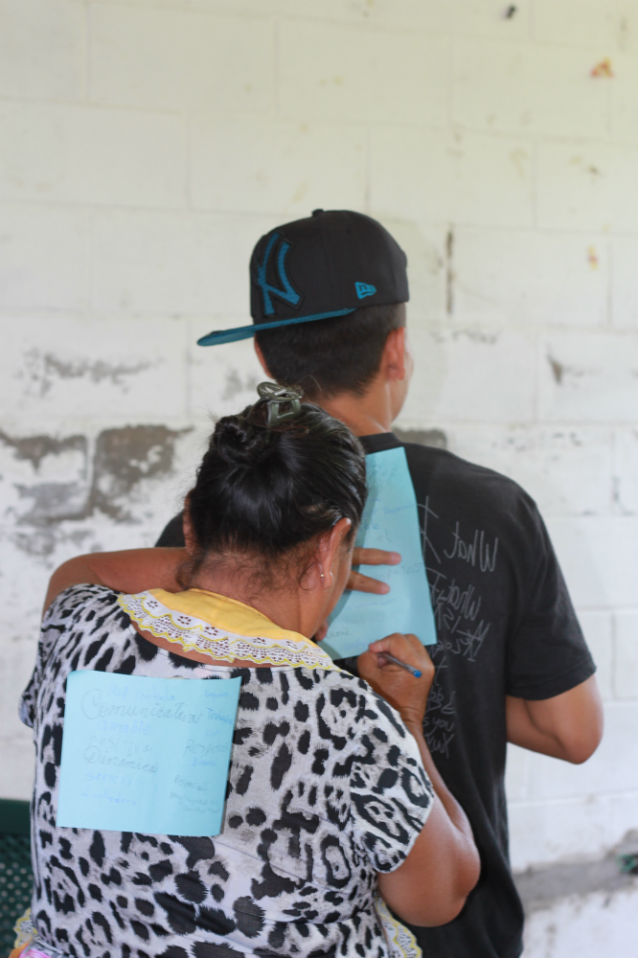

America and Lemus play a game with the group, in which each person had a paper taped to his or her back, and the others anonymously write characteristics that they see in that person. The point was to illustrate that the way we present ourselves and treat others sends strong messages about what type of person we are. Earlier that morning, America had forgotten about the meeting and was headed to sell fish by the Ilopango lake. Lemus passed her on the street. “He asked me, ‘Aren’t you going to the meeting, abuela?’” said America, who didn’t know Lemus before the dialogue group began. “When we walked together to the meeting I know the whole town was staring at me. I don’t care; our kids are our future,” America said.

A home in the community of Amatitan, Ilopango, El Salvador. In 2011, Ilopango was one of the most violent municipalities in the country, with an average of 113 murders per 100,000 inhabitants. (The world average is 6.9 per 100,000, according to United Nations Global Report on Homicides.) It is representative of the communities from which many children are now fleeing to the U.S.

Maria Alicia Hernandez, the director of a public school in the area, plays the paper game with Roberto Martinez, a community leader from La Selva. One year ago, when the roundtable first began, teachers and community leaders told gang members to stop extorting money and hanging out near the school. The gang followed through—a crucial first step in rebuilding trust. Now the discussion is about how to tackle the larger issues that create gangs and violence in the first place.

Magdalena Lopez, at right, is a 27-year-old psychologist who works at FESPAD. She led the community in a discussion about relationship building, discrimination and empathy.

Lopez was born into a violent neighborhood much like the ones where she now works through FESPAD. When she was 9, Lopez fled her home, choosing to move into an orphanage to be able to safely continue her schooling. Her high grades won her a spot in a college scholarship program in San Salvador, Nuestra Ahora, started by an American woman. Lopez graduated from the Jesuit University of Central America two years ago.

A decade ago, María Luz Panameño, pictured in the middle, was a union organizer with women sweatshop workers. She now is the president of the community where she lives, La Selva. She told the roundtable members about her formerly turbulent relationship with her 18-year-old daughter and what it taught her about dialogue. “My older sons were wonderful, but she was so rebellious…. I wondered what I did wrong,” Panameño said. The room was silent, save for the crowing of a rooster and traffic on the highway nearby. “We’re a poor family. I’m used to not having enough food at the table. But conflict in my family—that makes me feel like I want to die,” she said. Many in the circle nodded their heads empathetically. What saved their relationship was when she discovered how to listen and be more flexible with her daughter, Panameño said. Her oldest son is currently pursuing his master’s degree in Illinois, sponsored by a scholarship from the U.S. Embassy in El Salvador.

Public school teacher Nora Estela Mejia spoke about the challenges her students face. “Last week, a ninth-grade girl asked if she could call me ‘mom,’” said Mejia. Multiple of her students have been murdered and others have fled to the U.S. This experience led her to seek out the dialogue roundtable.

Being involved in the dialogue roundtable has a social cost, according to some of the members. A few refused to appear in photos because they feared being fired from their jobs. “Some people can only think of these kids as delinquents. They still think repression is the only answer,” said Yanira, who declined to share her last name. There is an entrenched debate in El Salvador about whether gangs are a criminal army or teenagers stuck in a violent life because they had few or no other options. Thus, while dialogue is part of the solution for some, others believe that only much more extreme responses will resolve the crisis. There is evidence that death squads, which murdered thousands of civilians during the country’s civil war, have reactived in the name of exterminating gang youth, the police and human rights ombudsman have said.

Maria Margarita Escobar is a 64-year-old community leader. “Until we learn to talk to one another, we’re only going to reap what we sew,” Escobar said.

Antonio Josue, an MS-13 member, reports back about the progress his subcommittee made in negotiations with the army about soldiers attacking youth in their neighborhoods. The abuse included soldiers who, while drunk and high, shot at teenagers. Police and soldiers also regularly pick up MS-13 members and drop them in rival 18th Street Gang territory, where many are killed before they can escape. The army colonel reported in the meeting that two of the abusive soldiers had been relieved of duty, Josue said. The colonel furthermore gave them his phone number, so they could call in the event of future human rights abuses.

Main Street in the community of Amatitan. In 2012, the two major Salvadoran gangs, MS-13 and the 18th Street Gang, brokered a truce supported by the government. The gang leaders agreed to stop violence and recruitment, to turn in weapons and to begin regular negotiations between incarcerated gang bosses. The homicide rate immediately dropped by half and foot soldiers of both gangs received orders to join local pacification efforts. An unknown number of these efforts cropped up in communities across the country. Some were sponsored by money from foreign governments, especially the European Union, but others, like this roundtable, were initiatives by neighbors tired of violence. Ilopango’s homicide rate fell so drastically that it was the first to be declared a post-truce “violence-free municipality” by the government. However in late 2013, the truce slowly fell apart—commitments weren’t fully kept by either the gangs or the authorities, many say—and the murder rate has risen back to its pre-truce level, making El Salvador once again one of the world’s most violent countries. Nevertheless, this roundtable forges ahead—evidence that, although the truce may have collapsed on an official level, the breathing room it offered gave rise to a decentralized, grassroots peace process that continues.

Jeanne Rikkers, a violence prevention expert at FESPAD originally from Minneapolis, summarized at the meeting that the roots of violence are deep in El Salvador. “In this country, we often confuse fear with respect,” Rikkers said. “Since the Spanish arrived 500 years ago, authorities have imposed their will through fear. People follow the law because we’re afraid of what happens if we don’t,” she said. “We’re not taught that the purpose of the law is to help us live well.”

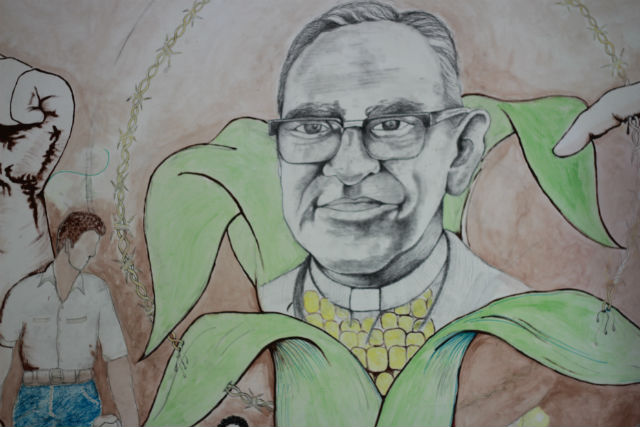

A mural in the FESPAD office of Archbishop Oscar Romero, assassinated by the U.S.-backed Salvadoran army in 1980, and who the Vatican is now moving to canonize as a saint. Archbishop Romero’s legacy inspired the creation of many human rights and peace-building organizations like FESPAD. But recent events in the country have made organizations involved in dialogue between gangs and civil society nervous. On July 29, the attorney general ordered the arrest of Father Antonio Rodriguez, a Catholic priest and the director of a violence prevention organization in urban Mejicanos, charging him with aiding the gangs. The attorney general announced on May 1 that he is also investigating one of the two brokers of the gang truce, Raul Mijango. Organizations fear that this signals a swing back toward repressive governmental attitudes and a criminalization of dialogue. “Our institution is clear that we’re facing pretty grave risks,” said Rikkers.

Photos by Danielle Mackey

About Danielle Mackey

Danielle Marie Mackey is a freelance journalist based in San Salvador and New York. She writes about law, public policy and human rights in Central America and the United States. Currently a graduate student at New York University, Mackey is originally from Iowa. More of her work is available at http://daniellemariemackey.com.

< Previous Article

September 26, 2014 > Staff

Officials Make Plans to Address Migrant Crisis, Despite Tensions

Next Article >

1 Comment

[…] crime while benefiting only the very rich, according critics, reports previous Dispatch contributor Danielle Mackey in The New […]

Comments are closed.