Argentina, News Briefs, Southern Cone

Prosecutor’s Mystery Death a Litmus Test for Argentina

April 17, 2015 By Kamilia Lahrichi

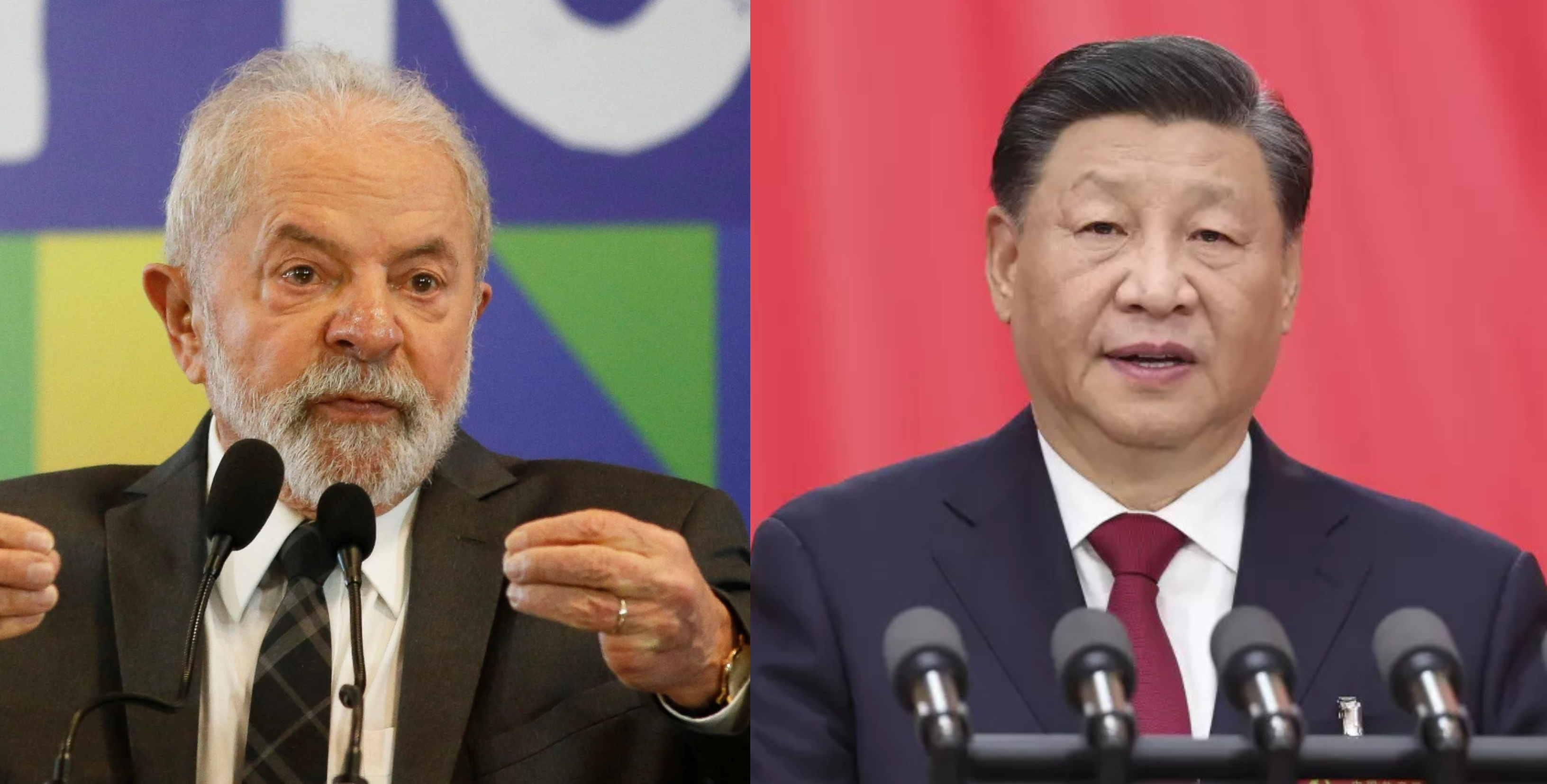

BUENOS AIRES — The mysterious circumstances under which Argentine Special Prosecutor Alberto Nisman died in January of an allegedly self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head has spawned a number of theories that challenge the official narrative put forth by the government. Nisman was found dead in his apartment on the night of January 18, one day before he was scheduled to testify at a congressional hearing, where he was expected to accuse President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner of covering up Iran’s role in a 1994 terrorist attack on a Jewish community center in Buenos Aires.

Government officials initially ruled Nisman’s death as a suicide, but couldn’t explain why a respected prosecutor would have taken his life before making the biggest case of his career. Others suspected that rogue Argentine intelligence agents had killed Nisman. Further theories posited that Syrian, Iranian or Israeli agents were involved. In March, Nisman’s family told reporters that an independent forensic investigation pointed to him being murdered.

The rumor-mongering reflects how the Nisman affair has plunged Argentina into turmoil at a time when the country faces troubling challenges, including 40 percent inflation, the devaluation of its currency, pressure from foreign creditors and rampant corruption.

Prior to his death, Nisman was appointed in 2004 as a Special Prosecutor by Fernández’s late husband, former President Néstor Kirchner, to oversee the investigation into the unsolved 1994 terrorist attack on the Jewish community center Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina in Buenos Aires that killed 85 people and injured hundreds. On January 19 — the day after his body was found — Nisman was slated to appear before Congress and present a 300-page report arguing that Fernández, in collusion with Argentine Foreign Minister Héctor Timerman, covered up Iran’s role in the attack. In exchange for shielding the Iranian terrorists, Tehran would deliver cheap oil to energy-starved Argentina, Nisman alleged.

Demonstrations for and against Fernández that bring together hundreds of thousands of protesters have become commonplace in the capital and across the country. Lawsuits working their way through Argentina’s notoriously crooked courts, as well as bombshell news reports, could renew the controversy at any time.

“The Nisman case was a sort of earthquake for Argentine politics,” said Sergio Berensztein, a political scientist at Torcuato Di Tella University in Buenos Aires. “We are seeing the aftershocks on a daily basis: conflicts involving the intelligence services, the justice system, other security forces.”

The Nisman case has resulted in a precipitous drop in confidence not only in Fernández but in Argentina itself. A February poll by Management and Fit found that Fernández’s popularity fell to less than 30 percent after Nisman’s death, a two-point drop. Anti-government protesters chant “They should all go away” — a reference to corrupt policymakers — and “national police, the national shame.”

“I have no faith in this manipulating government,” said Josephina Martinez, 40, who stopped by a memorial to Nisman in the Plaza de Mayo, near Argentina’s Casa Rosada, or Pink House — the executive mansion where Kirchner works. “This is not a country where institutions are very strong and where there is a desire to improve things.”

In her defense, Fernández argued that state intelligence agents provided false information to Nisman. She then announced the dissolution of the agency and the creation of a new spy bureau that would be more accountable and with limited surveillance powers.

In early March, federal Judge Daniel Rafecas dismissed Nisman’s case against Fernández and Timerman. Prosecutors have appealed Rafecas’ decision, suggesting the climate of uncertainty could linger for months.

The lack of closure presents problems. Whether or not Nisman’s allegations against Fernández are true, Argentina is undoubtedly facing an economic crisis that requires decisive presidential leadership. But, due to term limits, Fernández can’t run for office in October, meaning she could be a weaker-than-usual lame duck for months.

In the meantime, Argentina must come up with $1.5 billion in payments to foreign creditors — the country has defaulted on the loans, though Fernández denies it.

Argentina suffers from several other economic woes, namely a worsening recession, falling wages, a dearth of foreign reserves, increasing poverty and the devaluation of the local currency, the peso, by 20 percent in January 2014. A black market trades the peso at 13 percent at the time of writing. Private consultants say inflation reached 40 percent, whereas the National Institute of Statistics puts it at 20 percent. Finally, unemployment rate amounted to 7.5 percent in August 2014, according to official statistics, which are released twice a year.

Kirchner has her defenders too.

“I don’t know if Cristina is the best but she is the best we can get,” said Pablo Saldago, 55, a printer who took part in a recent pro-Fernández rally where he and others chanted in Spanish, “More than ever, we stand with Cristina.”

Since he works the night shift, Saldago said that he came directly to demonstration without sleeping. The wide majority of Kirchner’s supporters come from the working classes, the traditional base for her Justicialist Party founded by former Argentine demagogue Juan Perón.

In early March, Congressional Deputy Elisa Carrió, an opposition leader widely expected to run for president in October, published a report titled “The Lies of Cristina Kirchner in the Investigative Commission on the AMIA and the Embassy of Israel.”

She denounced Fernández’s “double position” and noted that the president’s “loyalties or political strategies changed her position on the tracks [of the investigation] or the defendants.”

Even Juan Alvaro, a 27-year old law student in Buenos Aires who supports the president, acknowledged that Argentina needed to change. The more he studies his country’s justice system, the more distressed he becomes, he said.

“It is dark, no one knows the employees, no one elects them,” he said. “They make decisions in an obscure way.”