Andes, Blog, Colombia, Dispatches

Colombia Halts Air Raids on FARC Rebels, But Steps Remain on Path to Lasting Ceasefire

March 12, 2015 By Leonardo Goi

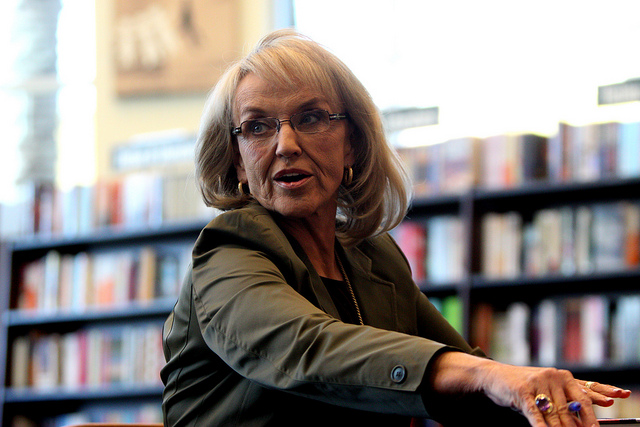

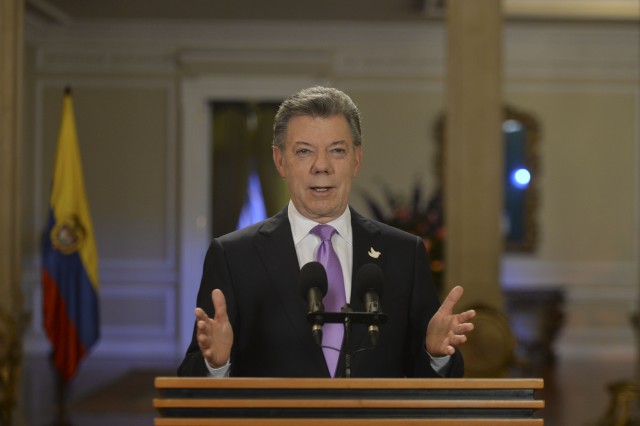

BOGOTÁ, Colombia — In a fifteen-minute long speech delivered on Tuesday evening, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos announced that the country’s armed forces will stop, for the next month, their bombing operations against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia.

Since August 2012, the central government and FARC rebels have been negotiating a peace agreement in Havana, Cuba, to put an end to Colombia’s 50-year-old internal conflict. On Dec. 20, the FARC had implemented a unilateral and indefinite ceasefire. The truce, as of today, still holds, and the guerrilla group’s ceasefire has led to a significant reduction in the levels of violence across the country. By declaring a month-long halt to the offensive against the rebels, Santos’ administration not only responds to the FARC’s unilateral truce but also takes a major step forward towards the de-escalation and final resolution of Colombia’s internal conflict.

Earlier this January, Santos had already instructed the government’s delegation in Havana to begin discussing with the FARC’s counterpart a definitive ceasefire that would involve both the armed forces and the rebels. The rationale behind Santos’ claim was simple: a bilateral truce could serve as the necessary step towards the end of the conflict — one of the last two items of the six-points agenda the delegations are yet to discuss in Havana.

But yesterday’s announcement should not be conflated with the sort of ceasefire Santos had spoken about two months ago. This is because what Santos outlined last night is not a definitive agreement, nor a ceasefire in any simplistic sense. Should the FARC threaten the Colombian people in any way — or, more generally, wage any threat against the country’s stability — Santos has made clear the halt to the army’s offensives shall be immediately lifted.

Seen from this angle, and contrary to the rampant criticism voiced by former President Álvaro Uribe’s opposition party the Democratic Center, Santos’ decision is not tantamount to a sudden giving up of the state’s monopoly of violence to the benefit of the guerrillas. The duty of the armed forces is to protect the Colombian people, and this is a prerogative that the ceasefire does not undermine. Nor does the deal entail the withdrawal or reconfiguration of the armed forces’ presence in the territory.

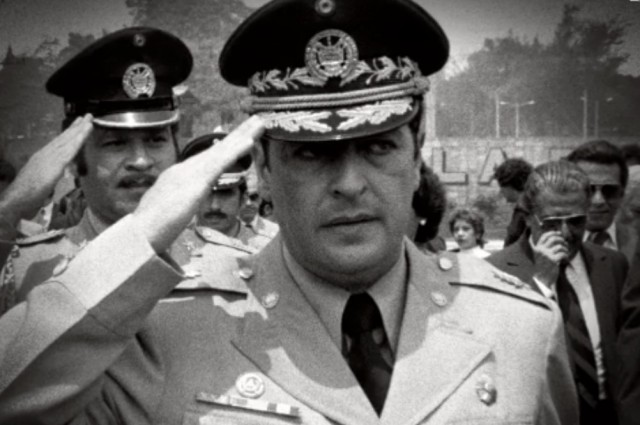

In this sense, the president’s deal is neither a bilateral ceasefire of the kind Colombia had witnessed during the peace process undertaken by former President Belisario Betancur (1982-1986), nor a system of territorial concessions akin to those granted to the FARC during the negotiations carried out under Andrés Pastrana’s administration (1998-2002). It is a temporary solution –- a trial, so to speak –- that now places the responsibility for what comes next on the FARC’s shoulders.

By implementing a unilateral ceasefire and making it dependent on the government’s avoiding any attack against the guerrillas, the FARC had effectively made Santos’ administration co-responsible for a possible breakdown of the truce, and the consequent crisis the peace talks would have suffered. By calling for a temporary halt to the hostilities of the armed forces, Santos has now shifted the burden back. Whether or not the current status quo shall be undermined is not something that concerns the government alone, but the guerrillas too. A breakdown of Santos’ deal on the part of the FARC would result in a tremendous loss of the political capital the group has acquired in over two years of negotiations. In this light, the president’s announcement formalizes what has already been a virtual bilateral ceasefire, and each side is all too aware of the risks the deterioration of the truce would bring about to dare disrupt the equilibrium.

The virtual stalemate has led to a drop in the levels of violence associated with the armed conflict unseen since the early 1980s, according The Conflict Analysis Resource Center. Civilian deaths have also decreased dramatically during the FARC-led ceasefire. But the intermittent clashes with the armed forces and the rebels’ attacks on the country’s infrastructure have not led to a parallel strengthening of people’s perceptions of security.

Convincing the public of the government’s strategies will most likely be one of Santos’ most difficult challenges. If the final peace agreement is to be put to a referendum as the president has proposed, then it is imperative for Santos to make sure any decision his government takes will be justified before the eyes of the Colombian people and the many victims the conflict has left. Appealing to the “supreme good of peace,” as the president did for the last third of Tuesday’s speech, can only work up to a point.

Another significant task will be fostering the support of the armed forces. Santos has already involved the army more directly in the negotiation process through the establishment of a sub-commission, in which military and guerrilla leaders have already begun discussing recommendations for the end of the conflict. Giving the army an active role in the negotiations is not just a way to legitimize the latter but will also help the government make sure a powerful source of dissent is co-opted and tamed down.

Whether or not Santos will prove capable of securing the public and army’s backing, the last great challenge will be to ensure that the peace process enjoys the input of those sections of the political spectrum that have so far been alienated by the talks. In other words, it will require Santos to involve — to the extent possible — Uribe’s party and its affiliates in the negotiating process.

In his speech, the president announced the establishment of an advisory board that will be joined by the likes of former presidential candidates Antanas Mockus and Clara López, former member of the M-19 rebel group and senator Vera Grabe and indigenous leader Ati Quigua, among others. The invitation has also been extended to the former Democratic Center presidential candidate Óscar Iván Zuluaga.

Whether the opposition will reply by supporting or criticizing Santos’ efforts, no peace can be premised upon the exclusion of a political party. The president’s decision to halt the army’s bombing against FARC targets is a major breakthrough toward the de-escalation of Colombia’s armed conflict, but its benefits will only be reaped if Santos turns the negotiations into a process that involves the Colombian people in its totality. However critical, the input of the opposition is necessary for the peace to be a legitimate and durable one. Somewhat paradoxically, establishing a dialogue with Uribe’s ranks may be harder for Santos than reaching a deal in Cuba. Nevertheless, the prospects of Colombia’s negotiations depend on both.

Leonardo Goi is a researcher working for Fundación Ideas Para la Paz, a Bogotá-based center that focuses on the analysis of armed conflict and its close relationship with Colombia’s development.

About Leonardo Goi

Leonardo Goi is a researcher for FIP, Fundación Ideas para la Paz, a Bogotá-based study center that focuses on Colombia's armed conflict and its repercussions on the country's development.