Dispatches, Peru

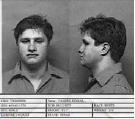

Ollanta Humala, “Neither Left, Nor Right” — An Interview

August 30, 2010 By Paul Alonso

What distinguishes you then?

We’ve said that we’re going to launch a frontal attack against corruption. We’re going to imprison those who steal from the country. I don’t know if they do that in other countries, but in Peru we’re going to do it. In fact, if you remember from the presidential debate, I proposed the contruction of a penitentiary in the jungle for politicians who steal and I looked at (President Alán) García when I said it. I don’t know if they do it in other countries, but we’re going to do it here. I want to be president of Peru, not Venezuela, not Bolivia, not the United States. I’m Peruvian.

What are Peru’s most pressing problems?

Inequality. The State treats some as first class citizens and others as second class. We have norms that amount to geographic discrimination. A kid from the coast—Lima, Arequipa or Piura—is not the same as a kid who is born in Puquio, in the high Andean zone, or Nauta, in the Amazon. There’s also discrimination based on the color of one’s skin or economic standing. The State doesn’t view a citizen with a (monthly) salary of $5,000 and one who makes 300 soles with the same eyes. The country also faces serious problems in education and public health. They’ve been turned over to the market, which is governed by purchasing power. All of this encompasses another problem—who does Peru belong to? To whom does Peru’s property belong and where does Peru’s wealth come from?

And who does it belong to?

Peru functions basically from taxes imposed on the mining sector, and the State doesn’t participate in the distribution of earnings from the mines’ wealth because it has given up ownership of the resource. If Peru makes its money from this, then Peru belongs to those who own the mining deposits. So, the country no longer belongs to us. What does Peru produce? Basically, cheap labor. And following this logic, the State doesn’t invest in education, because good education would be incompatible with the production of cheap labor.

Why do you think you could deal with these problems better than other candidates?

The others are afraid to look for a profound solution, one that goes to the root of the problem—which is a new constitution, a new economic model and the constuction of a new political class.

What would this new model look like?

A national market economy, which is the economic path that has been followed by the countries that are today called “first world.” It is the firm commitment of the State to its national industries, the construction of national economic groups, the maintenance of national ownership of natural resources, including subsoil rights. It’s also the commitment to an educational revolution.

How do you differentiate your current political thought from ethnic nationalism or from the militarism that other members of your family have proposed?

We don’t believe in ethnic nationalism. Trying to create a pyramidal social structure in Peru on the basis of skin color is some the Spaniards did in the era of colonialism. We believe in cultural nationalism. Skin color is not important, what matters is commitment to the project. We also speak of economic nationalism, which refers to the national market economy. Within this framework, we don’t accept these other forms of ethnic nationalism, which we’ve already seen how they turned out in Europe.

Many of your critics have called you “anti-establishment.”

That comes from those who are defending this system. And they say it that way because they don’t want to recognize that what we want is a better system. It’s not that we’re against systems, per se. This system is corrupt, perverse and discriminatory—it turns Peru into a colony in the middle of the twenty-first century, and democracy into keptocracy, a government of swindlers. It’s not that we criticize systems, because we always have to be in a system. What we want is a new system.

When you lost the 2006 election, your party rapidly disintegrated, demonstrating the precariousness of your political organization. How can you be sure that those who accompany you on your 2011 list won’t desert you again?

I don’t agree with that statement. When we ran in 2006, we didn’t have a political party. Were were a movement that fed from the force of an idea, which was nationalism. We had to run as guests with another party, the UPP (Union for Peru), who, once they got into Congress, changed their politics. This forced us to split off from the UPP to keep the current 25 nationalist congress members together and defend them so that they wouldn’t defect, which was our worry. On the other hand, party desertion isn’t a nationalist invention. It has a long history and Fujimori lifted it to new heights by buying congress members, and that’s been filmed. In our case, we expel party deserters. What happens is that APRA (American Revolutionary Popular Alliance) takes them and runs them as vice presidents. Party desertion is a cancer in Peru’s parliamentary system. And it needs to be corrected by a reform in which political parties will guarantee that congress members will not betray the voters. It’s a virus that nationalism is not responsible for…

7 Comments

[…] After losing in a second-round election to Alán García in 2006, controversial Peruvian nationalist Ollanta Humala is running for the presidency again. Get to know him in this interview with Paul Alonso. […]

[…] the Latin America News Dispatch presents an interview with Ollanta Humala, the most likely presidential candidate for the Peruvian Nationalist Party. (Let’s remember that […]

[…] poll puts Humala in second place, with 18.5 percent. A self-described nationalist, Humala eschews the political categories of “right” and “left,” though most observers view him as a […]

[…] Story — Leftwing nationalist Ollanta Humala held a very narrow lead as of late Sunday night over conservative Keiko Fujimori in Peru’s […]

[…] choosing Brazil as his first trip abroad as president-elect, Humala seems to be siding closer with the moderate leftist governments of the region and shying even more away from supporting more radical left-wing leaders like […]

[…] To learn more about Humala, follow this link to read the Latin America News Dispatch’s interview with him. […]

[…] been a transfer of votes precisely between nationalist candidate Ollanta Humala and you. Many people who voted for him five years ago now say they will vote for you. How are you […]

Comments are closed.