Andes, Colombia, Dispatches, Features

Strategy, Cease-Fires and Public Opinion: Inside Colombia’s Peace Process

July 13, 2015 By Daniela Castro

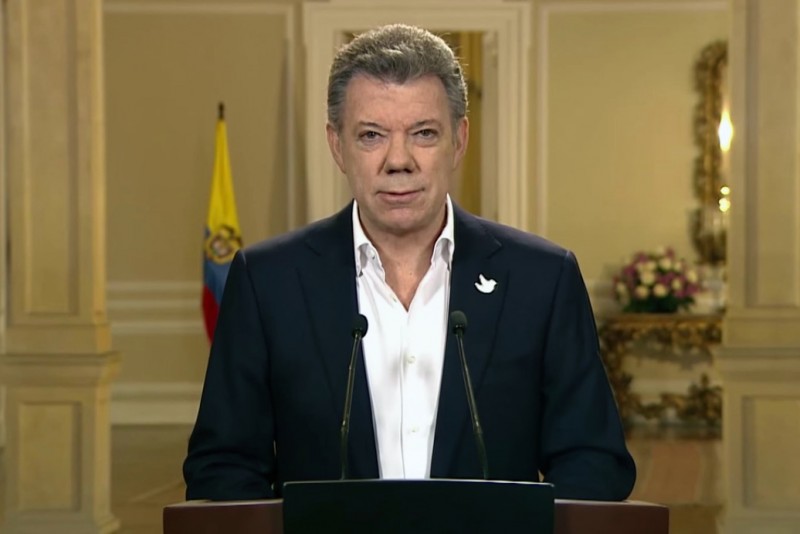

BOGOTÁ, Colombia — On Sunday, diplomats in Havana, Cuba announced that the Colombian government will de-escalate its military campaign against the FARC rebel group, if that group adheres to the unilateral ceasefire it is set to observe from July 20 onward. The announcement, made by the Cuban and Norwegian diplomats mediating peace talks between the FARC and the government of President Juan Manuel Santos, represents a historic move toward ending the war launched by the FARC in 1964.

Prior to the Sunday announcement, Angelika Rettberg, director of the Armed Conflict and Peacebuilding Research (Conpaz) program at the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, spoke with The Latin America News Dispatch. Rettberg, an expert on Colombia’s internal conflict and the peace process, spoke about issues ranging from the prospect of a bilateral ceasefire — which now appears more likely than ever before — to the drawbacks of setting a deadline for a peace agreement. She also spoke about the role of public opinion in the peace process. Rettberg’s insights elucidate the developments that led to this point and what is likely to come. The interview has been translated and edited for length and clarity.

What does it mean to negotiate in the middle of the war?

It means many things. On the one hand, it means the recognition of a massive popular will [to definitively end the 51-year conflict]. I believe that, in political terms, it was the most viable way to sell the peace process to a Colombian society that remains suspicious of the process and that learned bitter lessons from the last attempt at negotiating peace during the Caguán [peace process, which lasted from 1999-2002 and during which the government ceded a “safe zone” to the FARC].

Colombians are skeptical of a potential peace agreement. I believe the only way to sell a peace process to this kind of society — one that is not in crisis, that learned bitter lessons from the Caguán peace process and that is deeply skeptical of the prospect of the FARC demobilizing and accepting the consequences of a peace agreement — is to mount peace talks in the middle of the war.

Negotiating peace in the middle of the war also allows the government to make tactical bets throughout the process. I think the government decided to carry out negotiations in the middle of the conflict because it allows them to hold certain cards up their sleeve, to be used at a later time. The possibility of a bilateral ceasefire would the biggest example of this: not exhausting all the possibilities at the beginning and instead offering concessions gradually.

UN Humanitarian Coordinator Fabrizio Hochschild questioned the strategy of negotiating in the middle of the war, but at the same time he said that a bilateral ceasefire was not viable at this moment. What would it be like to negotiate in the absence of fighting?

I believe that a bilateral ceasefire is a kind of “big prize” in a more advanced stage of the process, when the most difficult obstacles have been overcome. A good example is the issue of transitional justice, because I think it is much more costly in political terms to take a step back from a ceasefire than to go on negotiating without it. In other words, continue with what the government was doing: in practice, the ceasefire was never officially declared, but the government slowed down operations against the FARC. By doing that, the government did not have to assume the political cost of declaring a ceasefire, or of a reversal because of attempts to sabotage the talks. If we know anything about peace processes, it’s that acts of sabotage occur all the time. There are always ups and downs.

From the point of view of a negotiation with a complex actor like the FARC, I understand the government’s approach of preserving a potential bilateral ceasefire until it is abundantly clear that the talks have made irreversible progress.

What are the main challenges of negotiating in the middle of the conflict?

The attempts at sabotaging the talks are an example. Whether deliberate or not, they expose the parties’ vulnerabilities. I think that is the most difficult challenge. The kidnapping of General Alzate last year, the ambush of the 11 soldiers, and the killing of more than 20 rebels in May are the kind of acts that test the will of the parties, and support the arguments of those who oppose the peace process. That is the risk.

To me, these challenges show that the process has taken on a certain level of resilience and a degree of inertia that goes beyond those who started it, and I think that is positive because it shows that the process of building trust, necessary to get out of this type of crisis, is underway.

There are two points that have been key in the discussions about the peace process, particularly after April’s FARC attack on the army in Cauca. One of them is the bilateral ceasefire. Should the government declare a bilateral ceasefire as a condition to de-escalate the conflict? What else can be done to de-escalate it?

Things like a partial ceasefire, which is what Santos did by putting a halt to bombings, but not calling a complete halt to other military operations. I believe that is the kind of thing that can be done to show will, because it is important to show will as well as strength — a difficult thing for the government to do. In addition, it is important how much progress has been made so far in terms of clearing landmines. Something I also think is essential is the arrival of the military at the negotiating table. Both the military and the rebels have agreed that these developments have been some of the most fruitful aspects of the whole process, and I agree with that. This has differentiated the current process from previous ones. The parties fighting the war are sitting at the negotiating table, in addition to those who finance it or lead it,and since they understand each other and work together in seeking concrete solutions to concrete subjects like the landmines and how to lay down arms, I think that the process builds confidence piece by piece, as opposed to focusing just on big agreements.

It will take time for those agreements to permeate Colombian society; it will certainly not be overnight. That is, for me a ceasefire is strictly that: all the fires put out across the country, which I do not think will happen. On the contrary, the process will pave its own path by gradually building up confidence.

The other point is to set deadlines for the negotiations. Should the government do this?

Deadlines are a double-edged sword. On the one hand, we know that at the moment when the presidential campaign begins — if a peace deal has not been signed by then — it is going to be much harder to get quick results. So much will have changed by then: public opinion, the negotiators’ energy levels, the economic conditions of the country that will have to finance the deal’s implementation. I think that would be risky.

I think we all agree that the sooner, the better, but at the same time saying, “if the peace agreement is not signed before April 2016, then we stop the negotiations,” is to dig one’s own grave. What will happen if the peace deal is not signed in April 2016 but in May and the parties have to break it? In that case, deadlines work more as a measuring stick for the negotiators and shouldn’t be explicit, because if they have to be broken, then one’s credibility is lost along with all the progress made.

I am sure that the negotiators have already set deadlines for the peace process, but the government is not going to say “if we do not have a deal by this date, then the peace process is over.”

We all thought this would go much faster than it has. We have learned that everything has been more difficult than expected. The FARC have been very effective in outlining their arguments. They may have taken losses militarily, but politically, they have had an enormous ability to make their point, and so things have not been easy. For example, in the truth commission — a name which doesn’t make much sense to me because we already have “truths” — the question is how do we demonstrate them, how do we assign responsibility, and how do we translate that justice. Still, I understand the issue of the truth as a “prize” that is given at the negotiation table as a way of saying “ok, you will have another chance to tell your own side of the story, if that brings you tranquility.”

Those things take time, but if the desired effect is fulfilled — that they demobilize and abandon the armed struggle — then it was worth it. It may have taken longer than expected, but it was worth it.

When deadlines expire, frustrations usually arise and expectations fail to be fulfilled. It’s politically onerous. That’s why setting explicit deadlines is so complicated.

What role has public opinion played in the peace process?

Public opinion is odd. It has not drastically changed in the recent past, not even during the Uribe presidency. In other words, even during the time of the Democratic Security Policy, most Colombians preferred a negotiated solution, according to polls. So the questions would be: What can be negotiated and in exchange for what? And that is where opinions become polarized and where the figure of the president plays an important role.

The fact that Santos is not so popular among Colombian society weighs heavily on public opinion more than anything else, as well as on what can be negotiated in the current peace process. Another issue is the fact that if you digs a little bit into where the big obstacle lies, you find that many Colombians have, I would say, a huge thirst for vengeance against the FARC. What needs to be done for the fear people feel towards the FARC — which is legitimate and well-founded given all the horrible things they have done — to be subordinated to people’s chief preference, which is the FARC’s withdrawal from the armed struggle, which will involve the group’s participation in a political process in which they will win some posts?

In addition, the government and the FARC have realized that they have to count on Colombian society. When this peace process postulated that it was “from the Colombians for the Colombians”, it meant “from all Colombians for all Colombians,” which includes the FARC and its constituencies and the state and its constituencies. And because Colombians will have to pay for the implementation of the agreements with their taxes, they will want to know where the money will go, where will it be invested.

As such, the big challenge of communication from the state towards society continues to be the pending matter. A lesson learned from the Caguán process is to keep the negotiations at a low profile, which has its own costs. Many average Colombians do not distinguish between violent phenomena in the country. People make connections or free associations, which are not rigorous from a conceptual point of view, but nonetheless exist as relevant perceptions.

I believe that the key thing about messaging is not so much telling people that the peace is good, that it will pay dividends, that the economy will grow, that more money will be spent in education and that it would be better to forgive, because some people do not want to bet on something uncertain when they feel a lot of fear. I think it makes more sense to ask people, “what do you fear?” and “why does the FARC’s name produce so many reactions?”

We cannot assume that a truth commission will resolve everything. On the contrary, it may mess things up if we start to dig too much. If we start to talk again about the El Nogal Club bombing, about the decades of imprisonment of soldiers, the treatment of hostages, and all of the other horrifying things that have happened, that will not necessarily help to reintegrate former combatants into civilian society. So for me the messaging is more about, “okay, what do we fear, and how can we address those fears?”

It remains unclear what role the truth commission will allow for the issue of justice, which is a very sensitive subject for many.

Colombia is different from other countries in that many “truths” have already been revealed, and few more things are left to be known, honestly. The problem lies in how we teach our history and in how we hold actors responsible. And that is the argument of the FARC. They have been saying, “we are not the only actor responsible here,” and while they have gone from saying, “we are victims” to “okay, we are one of the perpetrators,” they will not accept all the blame.

The other point is that, generally, the conflict and the peace process are not of great concern to much of the public. That is one of the unusual things that happen here. As a result of structural conditions in Colombia, many people simply do not care. In economic terms, Colombia is doing better than before, and in political terms — the peace process and the conflict — also much better than before, so the conflict is secondary compared to other concerns.

Regarding other peace processes, I do not have historical depth in terms of data, but I think it has changed qualitatively if you, for example, compare the peace process led by former President Belisario Betancur in the 1980s with the Coordinadora Nacional Guerrillera Simón Bolívar. At that time, the public held very idealistic opinions. It was thought that peace was around the corner — an issue of mutual human understanding, nothing more. And that was, in a way, how former President Andres Pastrana addressed the peace process in the late 1990s too. He thought the problem could be solved with whiskey and a conversation.

I think that Colombian society’s most important characteristic today is having acquired all that knowledge: The recognition that peace does not depend on the demobilization of one group, as well as understanding that peace is not easy to achieve, and that it is not around the corner. I think it is a healthy pragmatism. The difficult part is that it has a bitter side, which I mentioned before: it is much harder to sell this project of peace to a skeptical society.

Has public opinion put pressure on the negotiations?

There are two issues. On the one hand, the message sent to the government and the FARC is, “be careful, the public is not prepared to see these people participate in politics,” and the government has understood that it needs the support of the electorate for the implementation of the agreements. In the face of the October elections the government knows it needs to count on public opinion for a referendum, for example.

We have many precedents. One of them is Guatemala. They did a popular referendum in which the peace process was rejected by both the votes against it and the abstention rate. What can one do with that? There are several questions. Are the peace agreements going to be endorsed or not? How will they be endorsed? Will the elections be another form of referendum, like the second round in the presidential elections which gave Santos victory over a diverse coalition of sectors, united only by the fact that they wanted a peace process?

A referendum is where public opinion will really count, because the people who confuse cell phone theft with the peace process will vote “no” in the referendum, and then what? Then the big obstacle will be the electorate’s putting the brakes on whatever agreements have been reached.

In spite of the tensions that the negotiations have undergone — particularly in recent weeks with an increase in FARC attacks — the talks in Havana have proven to be somewhat insulated. However, Colombians’ patience is running out and support for the peace process continues to drop in the polls. How many more setbacks can the talks endure?

I think, on the one hand, it’s a game of inches. For example, the announcement of the truth commission gives the peace talks some breathing room, although as I said I do not believe that commission will have a great impact because we already have truths, we are only lacking implications. So I think that the agreement on agrarian reform, on illicit crops, on landmine removal, all of that helps with public opinion. On the other hand, the killing of the 11 soldiers devastated the talks’ approval ratings, but thousands of soldiers have been killed in this conflict, and never, as far as I remember, there has been such a massive rejection of the peace process.

The renewed awareness of Colombian society, who thought those things would no longer happen, points to a widespread perception of progress in the talks. And I think it hurts more when these things happen in a moment when people thought they would no longer occur, more than when one assumes that they are part of daily life, as it was in the 1990s. So I think that event, as tragic as it was, was positive in the sense that showed society was beginning to expect something different. So that is where the president’s favorability ratings fall because of the question, “How can he negotiate with the people committing these acts?” But at the same time, you begin to think, “Let’s stop this, this can’t continue to happen.” A little like the message of [government peace negotiator Humberto] de La Calle: “The reason why we negotiate is for these kind of things no longer occur.”

I do not know if Colombians’ patience is running out, but patience is like that. That at any moment, with an additional achievement — with a partial, additional agreement — the parties can resume negotiating.

At this point in the negotiations, is it possible to reverse the public’s opinion in the polls?

I think that anything can happen, for good or for bad. I hope that nothing bad happens and the process continues to move forward, but everything can change, as history has shown us throughout the world.

About Daniela Castro

Daniela is a Colombian freelance journalist currently living in New York City. She is pursuing a Master’s degree in Journalism at the City University of New York (CUNY) where she specializes in international and investigative reporting. Daniela worked for over three years at InSight Crime, a web-based think tank based in Medellin, Colombia, specialized in investigating organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. She has studied the armed conflict in Colombia as well as organized crime in Latin America, and more recently in Eastern Europe. She has covered issues related to human rights, immigration and organized crime. She has a bachelors degree in Political Science from the Universidad de Los Andes in Bogota, Colombia.